Personalized medicine is hot. The screening for polymorphisms in drug-metabolizing enzymes that alter the efficacy of certain drugs is now routine; and the sequencing of tumor genomes is enabling oncologists to select the most effective antineoplastic agent for a particular patient’s neoplasm. Now a third, truly personal, medical intervention is taking center stage: autologous cellular therapies. Cells are taken from the patient, modified and/or cultured and reinfused for their therapeutic effect.

Autologous, tissue-engineered therapies have made it to the market so far only in orthopedics (knee cartilage replacement), oncology (modified antigen-presenting cells to target prostate cancer) and cosmetics (fibroblasts cultured for use as dermal filler). However, 44 others are currently registered with the European Medicines Agency (EMA) as Advanced Therapy Medicinal Products (ATMPs) – meaning that they are in a framework that will enable approval for general use, trial results permitting. Four of the 44 are in ophthalmology and deal with corneal repair and a fifth ophthalmic application, for the treatment of uveitis, recently joined that list: TxCell’s Col-Treg.

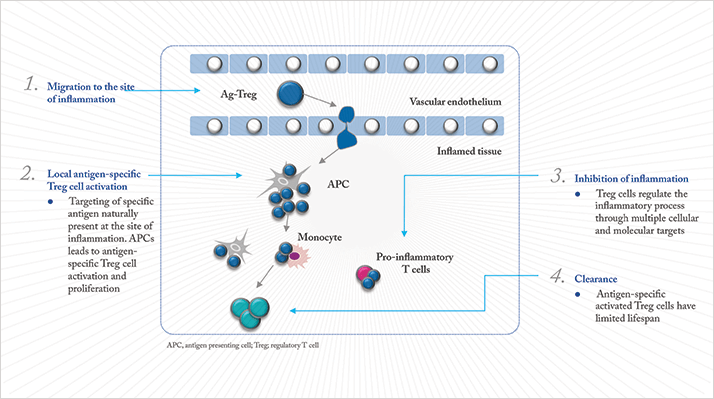

Col-Treg is a therapy based on regulatory T lymphocytes (Treg). “Tregs naturally occur in humans and animals, where they are responsible for immune tolerance – and they can ‘switch off’ autoimmune and inflammatory responses,” explains Arnaud Foussat, TxCell’s Vice President of Research and New Products. “We discovered that we can take a blood sample, isolate the Treg cells, train them to recognize an antigen that’s localized in a certain tissue, then culture them.” In the case of uveitis, that antigen is a part of the surface of collagen II (Figure 1). “Treg cells have a natural propensity to migrate to inflamed tissue,” says Foussat. “Col-Treg will migrate to the inflamed uvea, recognize collagen II, and display a therapeutic, anti-inflammatory activity.”

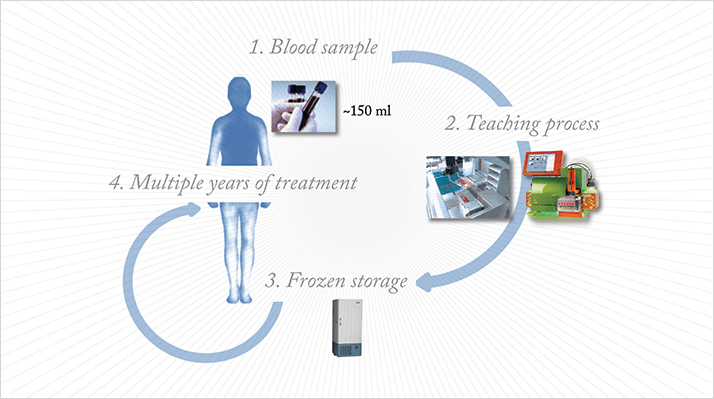

The product has nearly completed its pre-clinical testing, and should commence clinical trials by 2015. “If we draw 150 ml of blood, once, from a patient, we can produce enough Col-Treg to last three to five years,” Foussat says (see Figure 2). “We freeze the cells, and use them as needed.” The cells tolerate both freezing and thawing; even the first cells isolated, seven years ago, are still stable and usable today.