Retinitis pigmentosa (RP) is a serious but incurable inherited retinal disease. With patients in serious need of therapy that can slow progression, Okuvision has developed an innovative approach that has been approved for use as a treatment for RP. To find out more, we met with ophthalmologist Florian Gekeler and Okuvision CEO Alfred Stett to find out more about the company’s work in this essential area.

Please introduce yourselves and explain how you came to focus on retinal diseases, such as RP...

Florian: Well, I am an ophthalmologist, and back when I started my residency in the late 1990s, I joined the retinal implant project – and that was my first encounter with RP. Specifically, I was working on subretinal implants from then until around 2019. I first met Alfred in those early days – around 1999 – as he was very much involved in this same world. What really changed things for us was the news that a colleague in Chicago, Professor Chow, was also working on subretinal implants. He had something different to us, but discovered that, with extremely low-level electrical stimulation, you could improve visual function in RP patients – even in areas of the eye without the implant. This finding sounded very exciting but we wanted to gather our own data. After all, there can be a great deal of hype around electrical stimulation. I think you can stimulate everything in the body with electricity and get money for it; “Instead of doing your work out, just connect to a battery and get stronger!” Nevertheless, we got a sponsor which allowed us to develop and initiate two studies (1,2). Today, there is a larger study ongoing, sponsored by the German health insurance system (3).

Alfred: As Florian says, we have something of a shared history! My background is in physics with a focus on biophysics and I’ve always been interested incell culture techniques combined with semi- conductor techniques. After my PhD, I joined the retinal implant project in 1996, which had just started in Tübingen at that time. During that time, I took a closer look at the levels of electricity that retinal tissue can tolerate – obviously, an important safety issue in retinal implant development. In doing so, I found that a low level of current might have a beneficial effect on retinal tissue, protecting enough cells from apoptosis and dying (4). That was another trigger point for founding Okuvision in 2007. And yes, as Florian also mentioned, Okuvision has had quite a journey in terms of funding research and development. As the CEO of Okuvision, it is my responsibility to continually develop the OkuStim therapy and make it accessible to as many RP patients as possible.

What’s the scale of unmet need in the RP population?

Alfred: From an epidemiological point of view, RP is the most common inherited retinal disease and impacts around one out of every 4,000 individuals. This puts the scale of the unmet need at around 1.5 million worldwide.

What does the current treatment landscape look like – and what are the most promising avenues for future therapies?

Florian: There is no therapy available at the moment. There are many studies and interest is very high because many genes – I think around 200 – have been identified as having a role in the disease. But gene therapy is still in its infancy and we’re still waiting for a major breakthrough.

Alfred: The recent BBC investigation into pseudo-cures for RP was very important and shows there is still much to do in giving patients some hope – especially for those who don’t see a way of slowing their disease progression. It’s important to point out that, in contrast to these dubious treatments, we offer a medical device and a therapy that has been tested in clinical trials. The device itself has been through a very rigorous approval process that has proven its safety and efficacy.

Florian: And a very important distinction is that we publish our data! We use strict methods to assess efficacy, and we publish our stimulation paradigms.

Could you share a few details around the development process and the published data around OkuStim?

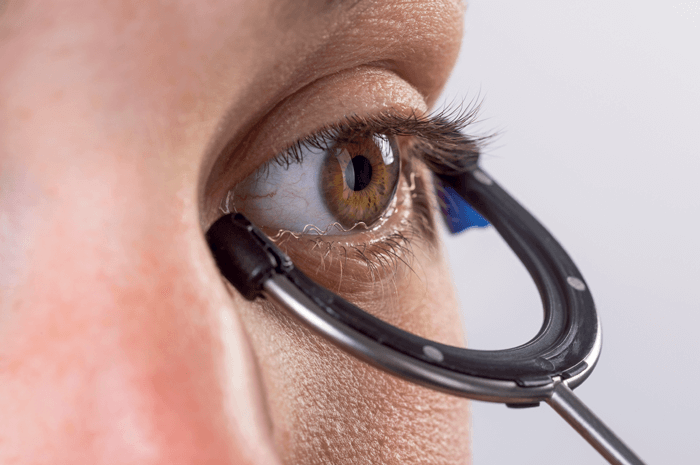

Alfred: Transcorneal electrical stimulation is a physical therapy wherein a current is delivered to the surface of the eye, which leads to excitation of cells in all layers of the retina. There have been numerous preclinical studies not just from our group but from other groups worldwide, investigating the impact of electrical stimulation on cellular and subcellular pathways in the retina. It was found that electrical stimulation produces cell- protective effects in the retina by activation of anti-apoptotic and anti-inflammatory processes. The results of our first clinical trial were published in 2011. It showed that the visual field of RP patients had improved by 17 percent after six weeks of transcorneal stimulation. Florian was one of the lead investigators in that study. A follow up study was published in 2017; however, in this second study, it was not possible to confirm the results of the first study. Our recently published exploratory reanalysis of the data provides an explanation for this discrepancy with a new hypothesis linking efficacy to current strength in the dosing of the therapy (5). The analysis showed a slowing of visual field loss with regular OkuStim application, with the effect depending on the current strength.

Florian: Alfred is correct. We performed those two studies but they were a little inconclusive. We had some significant findings in the first study, which were seen as a trend with a one-year-treatment in the second study, but without significance. But, as Alfred mentioned, the reanalysis provided some additional promising data, which brings us up to the current study, which is manufacturer independent and will continue for three more years (4). I think it’s important to note that this latest study – where a national health insurance system is investigating the significance of the results – represents a first in ophthalmology. Perhaps the main challenge when studying RP is the very slow progression; in short, to prove the efficacy of the therapy with reliable clinical data, we need long-term studies with many patients.

What should OkuStim users expect?

Alfred: That’s a very important question! OkuStim therapy aims to slow down or, at best, stop the progression of the disease. Patients cannot expect an improvement in vision – this is not possible with neuroprotective therapies such as OkuStim therapy. At the moment, we don’t fully understand the factors behind individual responses to treatment. We still have a lot to learn and a lot of open questions!

Could you talk about the safety profile?

Florian: If you follow the contraindications, it is completely safe! The only side effect is a temporary dry eye sensation which can be treated with artificial tear substitutes.

Alfred: In trial settings, we’ve had 400 patients use the device for something like 3,000 hours of stimulation and there have been no device related serious adverse events.

What challenges must be overcome to get this therapy to the biggest number of patients?

Alfred: Firstly, we need to get the therapy reimbursed by health systems. At the moment, patients have to pay for the therapy out of their own pockets. Secondly, we have to continue investigating the mechanism of action. The more we know, the more we can improve the efficacy of the therapy and this will allow us to expand the scope into tackling other ophthalmic needs, such as glaucoma.

Florian: Right! At the moment, the science is a little mysterious – we have many threads still left to follow, such as upregulation of neurotrophic factors, upregulation of certain genes, and so on. If we can answer some of these fascinating questions, I think that will be a great help. However, it is important to point out that the device is already available – you can buy it and use it now.

Alfred: To that point, we do feel there is some hesitance in the ophthalmology community about electrical stimulation therapy, but we must reiterate that there is no cure nor standard therapy available for RP – and I don’t think there will be for the foreseeable future. Okuvision’s number one task is to improve the knowledge base and work on efficacy; as efficacy improves, I think the ophthalmology community will be more open to this kind of therapy. It is safe, we know it can help slow progression, and we hope to see it widely adopted to give more RP patients a little hope.

References

- A Schatz et al., “Transcorneal electrical stimulation for patients with retinitis pigmentosa: a prospective, randomized, sham-controlled exploratory study,” Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci, 52, 4485 (2011). PMID: 21467183.

- A Schatz et al., “Transcorneal electrical stimulation for patients with retinitis pigmentosa: a prospective, randomized sham-controlled follow-up study over 1 year,” Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci, 58, 257 (2017). PMID 28114587.

- N Kahle et al., “[Transcorneal electrostimulation in retinitis pigmentosa : Protocol of a multicentric prospective, randomized, controlled and double-masked trial on behalf of the Joint Federal Committee (G-BA pilot regulation)]” Ophthalmologe, 118, 512 (2021). PMID: 33740090.

- H Schmid et al., “Neuroprotective effect of transretinal electrical stimulation on neurons in the inner nuclear layer of the degenerated retina,” Brain Res Bull, 79, 15 (2009). PMID: 19150490.

- A Stett et al., “Transcorneal electrical stimulation dose-dependently slows the visual field loss in retinitis rigmentosa,” Transl Vis SciTechnol, 12, 29 (2023). PMID: 36809335.