The problem with aging is that it doesn’t just increase the risk of developing age-related ophthalmic disease – it also increases the risk of developing age-related everything else. And co-morbidities require concomitant treatment, which, in the case of vascular disease, can include anticoagulant drugs.

Until about a decade ago, the options available were either intravenous, relatively short-acting, heparin-based agents (essentially for acute use only) or, quite literally, rat poison (oral warfarin). Warfarin is a tricky beast; it interacts with many foods and drugs, and its efficacy varies by the contents of a person’s last meal. It’s fair to say that pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics [PK/PD] can be... unpredictable. Plasma levels of warfarin (and its active metabolites) must be tightly controlled, which necessitates regular monitoring and dose adjustment, otherwise patients risk one of two potentially deadly extremes: bleeding or thrombosis. The drawbacks of warfarin spurred the development of new oral anticoagulants (NOACs) that have fewer drug and dietary interactions, more predictable PK/PD, and, therefore, less requirement for monitoring or dose adjustment. Take one or two pills a day and forget about it. They’ve made a big impact – in 2014, the bestselling NOAC of them all, rivaroxaban (Janssen/Bayer), made US$3.7 billion. But bleeding is still their biggest complication (1) – and in the eye, that can have serious consequences that may take a long time (or even require surgery) to resolve.

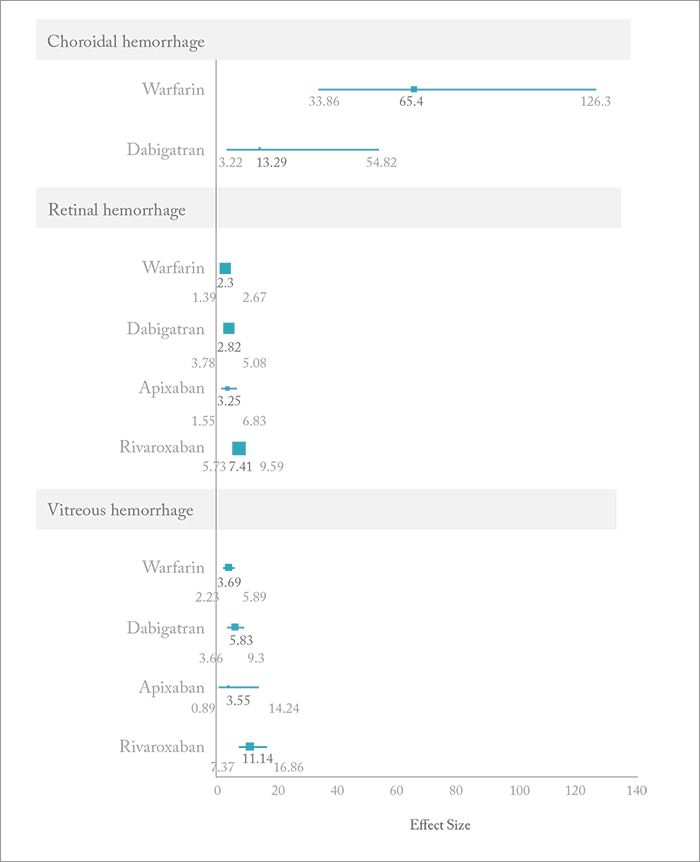

It’s known from epidemiological studies that NOACs do cause ocular hemorrhages – but the question for ophthalmologists is: are they more or less likely to cause bleeding than warfarin? A team from the University of British Columbia decided to find out by mining the World Health Organization’s Vigibase drug adverse reaction database from the period of 1968–2015 (a total of 11,582,092 events) to find out (2). They employed a disproportionality analysis to do so, computing the reported odds ratios (RORs) of all of the ocular (choroidal, retinal or vitreous) hemorrhage events that occurred with warfarin and each of the NOACs and then compared it with all other adverse reactions reported to Vigibase. They found 80 cases of intraocular hemorrhage with warfarin, and 156 cases with the NOACs (82, 65 and 9 for rivaroxaban, dabigatran and apixaban, respectively). They also found that warfarin had the highest signal for choroidal hemorrhage, whereas rivaroxaban had the highest signal for retinal and vitreous hemorrhage. Is warfarin getting a raw deal here? It’s been around the longest, so the authors suggest there “may have been a heavier predisposing to report hemorrhage incidents with the drug.” On the other hand, apixaban may be getting a better deal – the drug was associated with an excess of retinal hemorrhage events, but fewer ocular hemorrhagic events of any kind than the others, but this may be because it has been on the market for the shortest period of time. Perhaps more exposure will clarify the situation. There’s still work to be done. Operating on an anticoagulated patient isn’t fun. In the eye alone, bloody tears, hyphema and vitreal, subconjunctival, subretinal and choroidal hemorrhages can all occur, but there are no substantial recommendations or guidelines regarding the modification of anticoagulant regimens before ocular surgery. Instead, it’s entirely up to the surgeon’s judgement for each patient. With patients receiving NOACs – just like those receiving warfarin – the lesson appears to be: tread very carefully!

References

- RL Summers, SA Sterling, “Emergent bleeding in patients receiving direct oral anticoagulants,” Air Med J, 35, 148–155 (2016). PMID: 27255877. G Talany, M Guo, M Etminan, “Risk of intraocular hemorrhage with new oral anticoagulants”, Eye, [Epub ahead of print] (2016). PMID: 28009346.