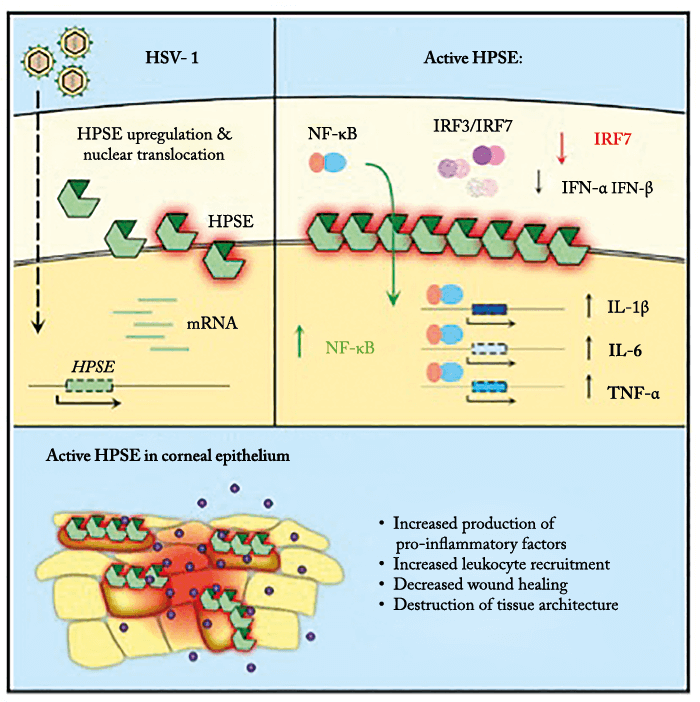

Once someone is infected with herpes simplex virus (HSV), they have it for life. But whilst persistent oral infection means recurrent bothersome and painful cold sores, persistent infection of corneal epithelium can cause keratitis – and the symptoms can persevere even when the episode of viral infection has cleared. How and why HSV-1-induced inflammation continues to plague the cornea once infection subsides has so far been somewhat of a mystery… until now. Enter a team from the University of Illinois at Chicago, USA, who have shown that heparanase, an extracellular enzyme that breaks down the glycosaminoglycan heparan sulfate (HS), drives the pathogenesis of HSV-1 corneal infection (1) (Figure 1). Their key findings?

- In mice with corneal HSV-1 infection, overexpression of heparanase worsened herpetic disease, delayed wound healing, and disrupted cytokine production.

- Heparanase translocated to the nucleus upon infection, driving expression of pro-inflammatory factors and activation of NF-kB.

- Inhibition of enzyme activity decreased viral spread.

What led to your research?

For many years we have focused on HSV infection, particularly in the eye because herpetic stromal keratitis is a major unresolved medical mystery. It has been known for some time that HS – a glycosaminoglycan important for corneal tissue organization – serves as a major initial attachment site for ocular HSV-1 and many other viral and bacterial pathogens. As heparanase is the only mammalian enzyme capable of breaking down HS, we investigated whether it could be involved in HSV infection of the eye. We previously showed that HSV-1 infection increased heparanase expression in corneal cells, and that the enzyme was required for effective viral release from these cells (2). We also found that overexpressing active heparanase in the cornea dramatically exacerbated keratitis symptoms in mice. This formed the basis for our recent paper which describes multiple mechanisms by which the active enzyme drives some hallmark features of epithelial and stromal keratitis (1).Did you find what you expected?

We were amazed that heparanase played such important roles in driving inflammation and other symptoms (e.g. neovascularization) in the eye, and were particularly surprised by its involvement in transcriptional regulation of pro-inflammatory factors that are already known to control chronic eye conditions including keratitis. As heparanase is normally found in the extracellular matrix (ECM), very little is known about its role in cell nuclei.Does HSV-1 affect just HS?

Although there have been reports that other ECM components are involved in the process of viral entry and may be modulated during infection, their interactions with HSV-1 are unclear. We have focused mainly on heparanase because HS and its associated proteoglycans are major attachment receptors for several pathogens. Since our original discovery in 2015, several other groups have replicated similar findings with other viruses, and we are excited that heparanase appears to have a universal role in infection.What impact do you foresee from your work?

With our findings, we have advanced the concept of a host-encoded virulence factor – a cellular protein that normally maintains homeostasis but can send several cellular pathways spiraling out of control when upregulated and activated by a virus. Our work points to important roles for heparanase in corneal inflammation and hopefully will draw additional attention to innate or resident molecules driving inflammation and ocular disease. As we’ve shown that inhibiting heparanase reduces corneal symptoms, we hope that a new line of therapy could soon emerge for better management of HSV keratitis. A therapy such as this could have unique dual benefits, stopping viral release and spread as well as reducing inflammation and neovascularization.References

- AM Agelidis et al., “Viral activation of heparanase drives pathogenesis of herpes simplex virus-1”, Cell Rep, 20, 439–450 (2017). PMID: 28700944. SR Hadigal et al., “Heparanase is a host enzyme required for herpes simplex virus-1 release from cells”, Nat Commun, 6, 6985 (2015). PMID: 25912399.