- In recent years, there have been major advances in the development of new sustained-release ocular drug-delivery systems

- Only a small number have achieved both global regulatory approval and commercial success

- Despite the challenges, significant market opportunities remain to enhance existing products or develop new technologies that offer improved treatment options for patients suffering from the major vision-impairing eye diseases

- In addition to opportunities, there are also obstacles facing developers of ophthalmic drug delivery systems and devices.

Currently, more than 10 million people in the United States are affected by the four major posterior segment diseases that cause blindness – age-related macular degeneration (AMD), diabetic retinopathy (DR), diabetic macular edema (DME) and glaucoma (1) – and their incidence is only set to increase as the population ages. But current therapeutic options for these diseases may, at best, manage the condition through slowing further deterioration or halting disease progression. It’s why many are looking for new solutions. Robust sustained-delivery of drugs is a beneficial option for both patients and physicians; long-term delivery of the drug directly to the back of the eye could enhance treatment compliance for patients who have long-term treatment regimens for these chronic diseases. Furthermore, long-term drug delivery could also help improve eyecare in developing countries, as well as address ethical dilemmas; in many developing countries (including China, India and Russia), practitioners often have one chance to address disease morphology because patients are often lost to follow-up. However, significant barriers exist when it comes to successfully developing and commercializing new sustained-release therapies in ophthalmology. Here, I explore the opportunities and obstacles facing developers of ophthalmic drug-delivery systems.

A short history of sustained release

The first polymeric inserts to release an ophthalmic drug over prolonged periods were used in the late 1800s in the UK, where gelatin inserts released cocaine for the purpose of local ocular anesthesia (2). But since the 1970s, only six sustained-release ophthalmic drug delivery products, four of which are intraocular devices, have been successfully brought to market. The first FDA-approved, sustained-release ocular product was developed in 1975 by California-based Alza Corporation and its innovative founder Alejandro Zaffaroni, following some brief development work in the Soviet Union on soluble ophthalmic drug inserts in the 1960s. Ocusert was an anterior extraocular system for patients with glaucoma that delivered pilocarpine at a near-constant rate; side effects were minimized as absorption peaks were avoided (3). Although Ocusert was a breakthrough innovation from Alza – who were the world’s leader in drug-delivery systems at the time – it was a commercial failure. Patient compliance was poor; it had to be inserted in the inferior fornix by the patient and only lasted seven days. However, much was learned from the failure of Ocusert. It became clear that drug delivery systems shouldn’t just focus on drug release rates and pharmacokinetics, but should also consider patient compliance and the level of comfort in the eye, as well as have physician endorsement to prescribe the product and support the patient. In 1981, Merck, Sharp and Dohme launched Lacrisert, a hydroxypropyl cellulose insert for patients with dry eye (4). Inserted in the lower conjunctiva using an applicator, the rod imbibes water and gels, causing the polymer to dissolve and the gel to erode, releasing the drug. Lacrisert remains on the market today (Bausch + Lomb), but with limited commercial success that I believe may be due in part to difficulty of insertion and potential blurring of vision. 1995 saw the launch of the world’s first posterior sustained-release intraocular delivery system, Vitrasert, resulting from a collaboration between Chiron Vision and Controlled Delivery Systems (CDS). Each Vitrasert implant contained a ganciclovir tablet coated with polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) and ethylene vinyl acetate (EVA) polymers, which facilitated diffusion of the drug (5). Indicated for cytomegalovirus (CMV) retinitis at the height of the HIV disease epidemic, Vitrasert delivered ganciclovir for approximately 6–8 months. It had initial resounding success in the USA and Europe; however, sales declined after 1998 because there were fewer cases of CMV retinitis (the first protease inhibitor – Fortovase – had become available and offered a greater degree of prevention against declining CD4 cell counts in HIV patients). Vitrasert subsequently exited the market in 2014. The world’s second intraocular posterior delivery product, Retisert, became available in 2005. Another CDS technology launched by Bausch + Lomb, Retisert has an orphan indication of non-infectious posterior uveitis (NIPU), and delivers fluocinolone acetonide over a period of about 30 months (6). Retisert was also studied for neovascular AMD and DR, but clinical trials failed to meet their endpoints. The third intraocular sustained-release product was Ozurdex, a dexamethasone intravitreal implant launched by Allergan in 2009, which is used for the treatment of adults with macular edema after branch retinal vein occlusion (BRVO) or central retinal vein occlusion (CRVO), noninfectious uveitis and DME (7). An anterior version of Ozurdex, Surodex was also developed by Oculex Pharmaceuticals (who were acquired by Allergan in 2003). Like Ozurdex, it was a bioerodible dexamethasone implant that delivered steroid at a continuous level for 7–10 days. Although intraocular placement of two Surodex implants was demonstrated to be safe and effective in reducing intraocular inflammation after cataract surgery, and superior to eye drops in reducing inflammatory symptoms, Surodex never completed its clinical trials (8)(9). The concept of anterior drug-delivery was however widely accepted as a potential breakthrough and remains so today. The fourth intraocular sustained release product to hit the market was Iluvien – an intravitreal fluocinolone acetonide implant in an applicator from Alimera Sciences that delivers sub-microgram levels of drug up to 36 months after implantation (10). Iluvien gained European approval in 2012 and USA approval in 2014 for the treatment of DME in patients who have been previously treated with a course of corticosteroids and did not have a clinically significant rise in IOP; it is now approved in 17 European counties, with further approvals and reimbursement expansion expected.Barriers, challenges and the Holy Grail

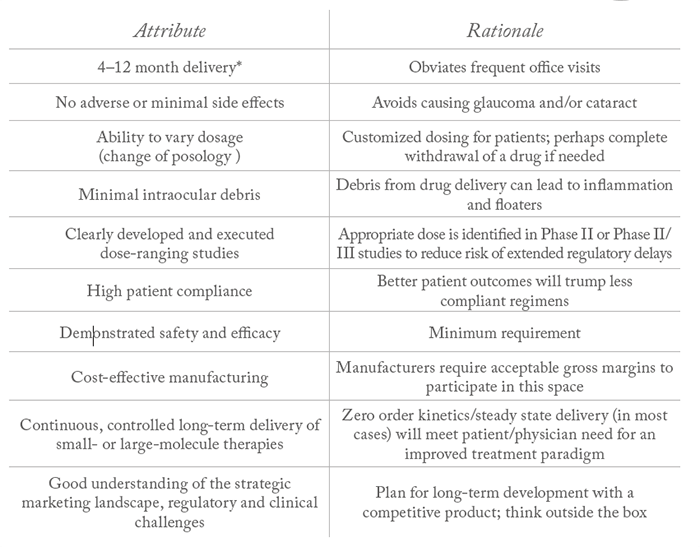

But why have so few sustained delivery devices made it to market? It is primarily because the pathway for developing a new therapeutic is complex, expensive and risky. About 50 percent of new systemic drugs fail because of issues with safety, toxicity and pharmacokinetics (11–13). With only four approved posterior-segment sustained release products by year end 2016, it is clear that there are challenges to the successful development of drug delivery devices. In 2009, a major drug delivery forum identified the following as key barriers to new effective sustained-release treatments and drug delivery technologies (DDTs)(14):- Developing an effective product

- Identifying and implementing the best delivery method

- Using the appropriate animal model for drug safety and efficacy

- Identifying an adequate patient sample and developing a clinical trial treatment design or plan to attain a satisfactory endpoint

- Locating a company to finance the product and guide it into the commercial market.

- Refillable drug reservoirs.

- Cell-based programs, including stem cells for neovascular AMD and other blinding diseases.

- Photo crosslinking technology with UV light for both small and large molecules.

- Microparticle and nanoparticle systems for neovascular AMD, glaucoma, including neuroprotection and potentially into the anterior segment for dry eye and corneal disease.

- Novel adeno-associated viral variant technology for long-term protein delivery to the eye in DME, neovascular AMD, and other conditions.

- Prostaglandin analog delivery systems for ocular hypertension and open-angle glaucoma.

- Topical semifluorinated alkane delivery, enhancing drug solubility for both posterior and anterior segment applications.

- Proprietary hydrogel technology.

- Suprachoroidal delivery or implants, including injectable suspensions.

- Infrared light-initiated polymer delivery.

- Injectable polymer-based protein delivery systems.

- Topical peptides for neovascular AMD and corneal injuries.

- Contact lens delivery systems.

- Iontophoresis.

An eye to the future

With increased understandings of diseases and conditions, as well as rapidly evolving technology to deliver agents specifically and effectively to the eye, the next decade promises great strides forwards in therapy for many currently poorly treated or untreatable ocular diseases. However, because of the large number of products in development, new DDTs should ideally be ‘disruptive.’ They must offer true innovation to both patients and doctors, meet a significant market need, and be clinically feasible and potentially reimbursable. Michael O’Rourke is the Founder and CEO of Scotia Vision, LLC. He has over 30 years drug delivery experience across ophthalmology, periodontal and pulmonary markets in sales, marketing, product launch, strategy development and global commercialization.References

- World Health Organization. “Blindness and Visual Impairments”. Available at: http://bit.ly/2Apii5f. Accessed November 7, 2017. EM del Amo and A Urtti, “Current and future ophthalmic drug delivery systems: A shift to the posterior segment”, Drug Discovery Today, 13, 135–143 (2008). PMID: 18275911. IP Pollack et al., “The Ocusert pilocarpine system: advantages and disadvantages”, South Med J, 69, 1296–1298 (1976). PMID: 982104 Bausch + Lomb, “Lacrisert package insert”. Available at: http://bit.ly/2hObciR. Accessed November 7, 2017. Vitrasert, “Summary of product characteristics”. Available at: http://bit.ly/2Ag7bKV. Accessed November 7, 2017. Bausch + Lomb. “Retisert prescribing information”. Available at: http://bit.ly/2zBd2y5. Accessed November 7, 2017. Allergan, “Ozurdex prescribing information”. Available at: http://bit.ly/2AgyhSl. Accessed November 7, 2017. DT Tan et al., “Randomized clinical trial of a new dexamethasone delivery system (Surodex) for treatment of post-cataract surgery inflammation”, Ophthalmology, 106, 223–231 (1999). PMID: 9951469. DT Tan et al., “Randomized clinical trial of Surodex steroid drug delivery system for cataract surgery: anterior versus posterior placement of two Surodex in the eye”, Ophthalmology, 108, 2172–2181 (2001). PMID: 11733254. Alimera, “Iluvien prescribing information”. Available at: http://bit.ly/2iDTCxA. Accessed Npvember 7, 2017. JF Pritchard et al., “Making better drugs: Decision gates in non-clinical drug development”, Nat Rev Drug Discov, 2, 542–553 (2003). PMID: 12815380. LJ Gershell and JH Atkins. “A brief history of novel drug discovery technologies”, Nat Rev Drug Discov, 2, 321–327 (2003). PMID: 12669031. I Kola and J Landis. “Can the pharmaceutical industry reduce attrition rates?”, Nature Rev Drug Discov, 3, 711–715 (2004). PMID: 15286737. HF Edelhauser et al., “Ophthalmic drug delivery systems for the treatment of retinal disease: basic research to clinical applications”, Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci, 51, 5403–5420 (2010). PMID: 20980702. Scotia Visio, Drug Delivery Research Model (2011). Data on File: Scotia Vision. Market Analysis & Development (2016).