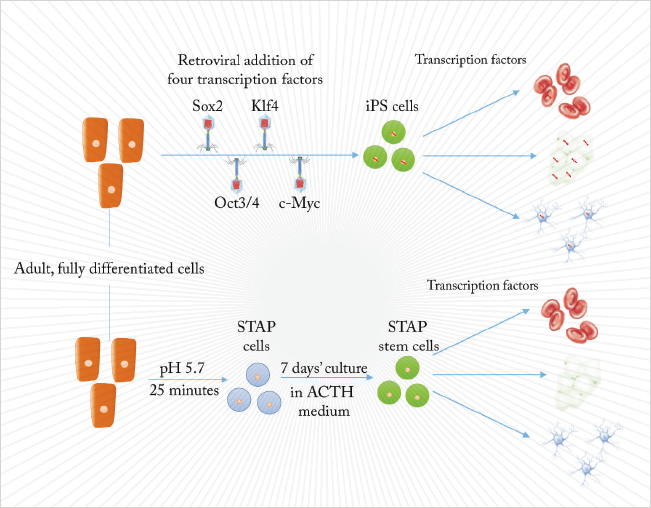

Stem cells are not easy to produce. Unless your parents arranged to harvest some from your umbilical cord at birth, embryonic stem cell-based therapies have the disadvantage of not being yours, risking rejection just like any heterogeneous transplant. The first alternative was to create stem cells by nuclear transfer into oocytes, or by fusion with embryonic stem cells. Then, in 2006, Takahashi and Yamanaka (1) showed that differentiated, adult cells could be reprogrammed by the insertion of four genes. Such cells could differentiate into any cell type of the body and were termed induced pluripotent stem cells (iPS).

That has been the state of the art, until now. In a Nature paper published in January, Haruko Obokata and colleagues took differentiated cells from a week-old mouse, cultured them in a low-pH (5.7) cell culture medium and created Stimulus-Triggered Acquisition of Pluripotency (STAP) cells (2). While STAP cells are hard to culture, they can form any cell type that an embryo can, including the trophoblasts of the placenta. Slight changes to the culture medium produced STAP stem cells, which are pluripotent, proliferative, and can develop into any adult mouse cell type. Stem cells from an acid bath might seem too good to be true. We spoke to Jamie Davies, Professor of Experimental Anatomy at Edinburgh University, and author of the textbook, Regenerative Medicine, to find out what it means for the clinical development of stem cell-based therapies.

What is the big breakthrough here? Treating cells with acid does not involve direct manipulation of genes or require the transfections of genetic materials. There is, therefore, a greatly reduced risk of the process turning a patient’s cells into something nasty, like a neoplasm, for example. Will it save time? It is a little faster, but the time-consuming step is verification of pluripotent stem cells and their differentiation towards building the tissue you want, rather than making them in the first place. Although there is a cost saving.

Does it mean that stem cell therapies will hit the market sooner? Ultimately, the time to ‘market’ depends on safety testing, and that will have to be done whatever the method of making pluripotent cells. This method looks safer, so may have a higher probability of passing those tests, but it’s important to remember that pluripotent stem cell generation is measured in days or weeks depending on what method is used (this one or a traditional one), whereas clinical trials are measured in years. Saving a few weeks does not really have much of an impact. How significant are the findings for stem-cell research and medicine in general? They may alter our understanding of what return to pluripotent stem cell state is – even raising the question of whether ‘traditional’ methods (1) also work by stressing cells. We may also have misunderstood the robustness/fragility of the differentiated state, and we could now have fresh insight into the association between chronic tissue injury and the risk of neoplasia – maybe cells become stem-like in response to the stress of chronic injury, and this part of the step to founding a neoplasm is not actually a story of genetic mutation.

And its significance for the future of stem cell therapies? If all of this holds up, and especially if a range of stressors of cells works, then a lot of intellectual property in the iPS field can be bypassed, potentially allowing more competition in the field. But beware of hype. This is genuinely exciting – folk in my lab dropped what they were doing to discuss it, and to come banging on my door to show me the paper. There is not, though, a one-to-one relationship between what is exciting to basic scientists and may open the door to new discoveries, and what is useful for fast and efficient generation of therapies. The slow and vastly expensive path to regulatory approval remains. A new design of running shoe may be half the cost of the old one and take half the time to put on, but this has little effect on the effort demanded by a marathon.

References

- K. Takahashi, S. Yamanaka, “Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors”, Cell, 126, 663–676 (2006). doi:10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.024. H. Obokata et al., “Stimulus-triggered fate conversion of somatic cells into pluripotency”, Nature, 505, 641–647 (2014). doi:10.1038/nature12968.