- Although trabeculectomy is often effective in lowering IOP, the procedure comes with the risk of conjunctival scarring, treatment failure, and complications, such as bleb failure, oversized bleb formation, bleb dysesthesia etc.

- For patients with OAG, one alternative is stab incision glaucoma surgery (SIGS), which creates an intentionally compromised corneoscleral tunnel through a single stab or small incision

- Advantages of SIGS include less fibrosis, posteriorly-directed flow, and a larger area of available virgin conjunctiva for future surgeries

- Here, I offer an overview on how to perform SIGS, and explain why it could be a better primary surgery for patients with OAG and no prior conjunctival dissection.

Though trabeculectomy can be effective in lowering IOP, it has a high failure rate and many patients suffer complications post-operatively. One of the main problems with trabeculectomy is that, when creating the flap, you’re creating a conjunctival wound that is going to heal by scarring – and scarring is one of the major reasons for failure. How do we get round these problems? By making the conjunctival incision as small as possible by performing stab (or small) incision glaucoma surgery (SIGS) – a procedure I introduced for patients with open angle glaucoma (OAG) in 2013. The basic principle of SIGS is very simple – it’s a single 2.8 mm keratome incision straight through the conjunctiva and sclera into the cornea and the anterior chamber. This corneoscleral tunnel is then compromised by punching the inner corneal lip to create a controlled leak for aqueous drainage. Tunnel trabeculectomy has been described previously as successful filtration surgery (1)(2)(3), and whilst SIGS uses the same concept, the scleral tunnel is created in one step as opposed to tunnel trabeculectomy, which first creates a flap in the conjunctiva and also has a triplanar tunnel as opposed to the biplanar nature in SIGS.

Why perform SIGS?

There are several key advantages to performing SIGS: reduced risk of fibrosis, posteriorly-directed aqueous flow, simplicity of the procedure and post-operative management, as well as economic advantages – it’s also faster to perform than trabeculectomy. I have been performing SIGS since 2013 and, in 2016, we at Dr. Agarwal’s Eye Hospital and Eye Research Centre published results from a prospective interventional case series of 17 patients (4), which are summarized in Box 1 (SIGS Case Series). We are currently at a much larger series. One of the main advantages of SIGS, reduced scarring, speaks for itself –decreasing the amount of conjunctival dissection means less scar formation. The small incision also preserves drainage channels in the sub-conjunctival tissue to a much larger extent than in trabeculectomy, meaning you are likely to get better subconjunctival drainage. Complications are also minimized, because there is no flap. Of course, the risk of fibrosis is not abolished, and mitomycin-C (MMC) can be given pre-operatively as a sub-conjunctival injection (0.1 ml of 0.005% or 0.01%) or intra-operatively as a MMC-soaked sponge applied to the tunnel (0.01 or 0.02% for two minutes). Better aqueous drainage is another main advantage of SIGS over trabeculectomy. The tri-planar flap created by trabeculectomy provides three directions of flow; both horizontal directions as well as posteriorly. But glaucoma surgeons only really want posteriorly-directed flow as horizontal flow to either side of the flap can lead to oversized and overhanging bleb formation and bleb dysesthesia. With SIGS, there is no sideward flow because all flow is directed posteriorly, so the risk of oversized bleb formation and related complications is reduced. From my experience, post-SIGS blebs are more diffuse posteriorly than those formed after trabeculectomy.SIGS also maximizes the amount of residual virgin conjunctiva. In conventional trabeculectomy, when a large area is dissected in the first surgery, the available area of untouched conjunctiva for second surgeries becomes quite limited, increasing the risk of failure caused by fibrosed conjunctiva. SIGS leaves a large area of absolutely intact conjunctiva so it is easier to perform repeat procedures – crucial for patients with glaucoma. You can start with a small incision in the superior quadrant and, if that first surgery fails, you can then move to other quadrants.

- A total of 17 patients underwent SIGS with pre-operative subconjunctival MMC.

- Mean reduction in IOP from pre-operative values was 38.81 ± 16.55 percent (p<0.000).

- Mean number of topical medications was reduced from 1.35 pre-operatively to 0.59 post-operatively (p=0.025).

- Post-operatively, 64.70 percent of patients achieved complete success, defined as an IOP <18 mmHg with no medications; 82.35 percent maintained an IOP <18 mmHg with two medications.

- Intra-operative complications encountered were premature entry, trapdoor hinging of internal corneal lip, conjunctival buttonhole, very small Descemet’s detachment and nonbasal peripheral iridectomy (all n=1; all managed or no intervention taken).

- Six patients encountered post-operative complications of uncontrolled IOP, of which three were managed medically and three underwent repeat surgery.

- No sight-threatening complications were reported (4).

How to perform SIGS

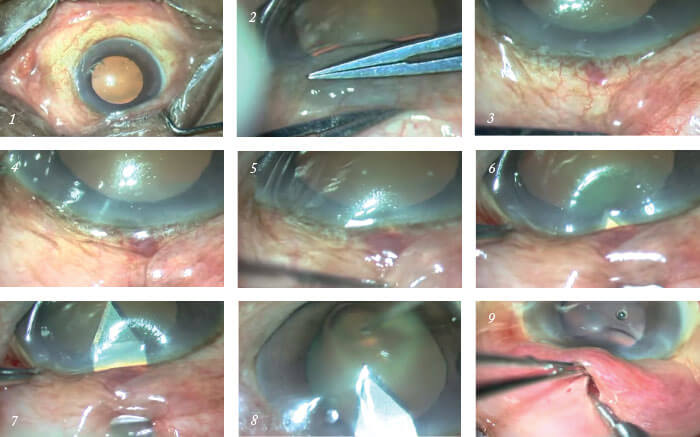

After peribulbular anesthesia (and optional MMC) has been applied, the first steps are to achieve a mobile conjunctiva by loosening the speculum and to push the conjunctiva downwards using a two-handed sliding technique (Images 1 and 2). A superior site is preferable as the supero-nasal fornix is short and the conjunctiva cannot be pushed as much in this location. 2.8 mm keratome entry. Position the tip of a 2.8 mm bevel-up keratome 1.5 mm from the limbus and begin to tunnel forwards. The keratome should just be visible through the overlying sclera and conjunctiva (Image 3). Whilst the tunnel is being dissected, the eye position should be controlled by holding the limbus with strong one-toothed forceps (Image 4). Creating the corneoscleral tunnel. The scleral part of the tunnel should be short and shallow – the ideal length of the entry incision is 1.5 mm for the scleral component and approximately 1 mm into the cornea (Images 5 and 6). At the limbus, the blade tip should be angled anteriorly to match the corneal curvature. The blade can then be introduced 0.5–1 mm into clear cornea before entering the anterior chamber in a horizontal plane parallel to the iris. Entry up to the shoulder of the blade should be made, avoiding both Descemet’s membrane and the lens capsule (Image 7). Downwards pressure should be avoided while entering the anterior chamber.Remove the blade in a smooth backwards movement while holding the eye at the opposite limbus (Image 8); sideward movement of the blade can slice tunnel sides and slow withdrawal can cause the anterior chamber to shallow. Instill viscoelastic into the anterior chamber through a paracentesis or through the SIGS tunnel entry. At this point phacoemulsification and IOL implantation can be performed if the surgery is being combined with cataract removal; the SIGS tunnel will not leak as it is self-sealing because the ostium has not yet been created. Phacoemulsification should be performed with the main and side ports placed on either side

of the tunnel.

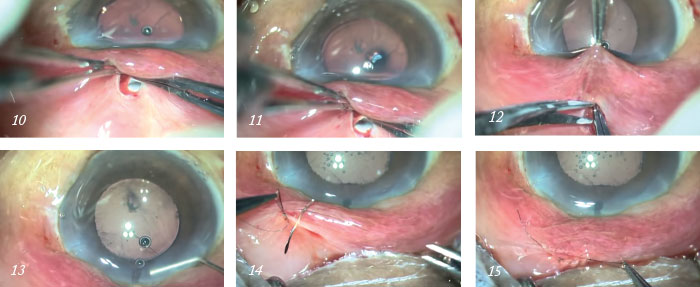

Creating the ostium. Slide a 1 mm Kelly Descemet’s membrane punch in unretracted position and facing sideways along the tunnel and into the anterior chamber. Next, facing downwards, punch the internal lip of the corneal section and punch vertically backwards; horizontal enlargement is not required. Once the limbus is reached, the tunnel can be examined by retracting the conjunctiva; the extreme edge of the final punch should be just seen deep within the tunnel (Images 9, 10 and 11). Irrigation over the tunnel can help with easy visualization.

Peripheral iridectomy. Shallow the anterior chamber. Insert angled non-toothed forceps and grasp the iris near its base just below the ostium. Retraction of the conjunctiva with non-toothed forceps by the assistant helps with visualization. Using curved Vannas scissors, cut the iris near its base (Image 12). Push the iris back into anterior chamber, ensuring that no iris is trapped in the tunnel (Image 13). As in trabeculectomy, a peripheral iridectomy is not an absolute must, however, it is preferred to be done in all cases as it avoids iris tissue blocking the ostium.

Checking the leak. Wash out viscoelastic and assess leakage through the SIGS tunnel by irrigating balanced salt solution (BSS) through side-port irrigation; there should be a free flow of fluid. If it is difficult to visualize flow, hold the conjunctival cut closed while irrigating and look for bleb formation. Additional punches can be taken if the leak is inadequate. Suture the 2.8 mm conjunctival cut with a running 10-0 nylon suture and knot down with final loop – this twists the edges of the conjunctival cut making it leak proof (Images 14 and 15) – Tenon’s capsule should not be included. Subconjunctival medications 0.5 ml garamycin (40 mg/ml) and 0.5 ml dexamethasone (4 mg/ml) can be given into the inferior fornix. Post-operative management is similar to trabeculectomy.

The results so far with SIGS have been very encouraging. Though the procedure isn’t meant to completely replace trabeculectomies, it provides a good primary surgical option for patients who might have been considered for a trabeculectomy, bringing advantages such as minimized scarring, posteriorly-directed flow, fewer post-operative complications, as well as preserving conjunctiva for any additional future surgeries. It is also a quicker surgery to perform than trabeculectomy, which can increase efficiency in the clinic and provide economic advantages. Not every patient is suitable for the procedure, however, and exclusions include prior trabeculectomy, conjunctival scarring, angle-closure glaucoma and prior uveitis. But this isn’t always cut and dry: though I personally wouldn’t consider SIGS for a patient who already has conjunctival scarring (for example, from retinal detachment surgery) because they won’t harness the benefits of the procedure, I have heard from many around the world who are performing SIGS in these complex cases and are happy!

As with all surgeries, there is a learning curve involved. But surgeons already performing trabeculectomies will be able to manage SIGS as well; it is also easy to convert SIGS to a conventional trabeculectomy if needed. We’ve had many surgeons come to us from abroad just to learn this technique, as well as many who’ve seen the procedure online or at conferences, and it has been great to hear how happy they are with the results of the surgery. I hope that more ophthalmologists will be encouraged to adopt the approach with their patients. Soosan Jacob is a senior consultant ophthalmologist at Dr. Agarwal’s Eye Hospital and Eye Research Centre in Chennai, India.

References

- RA Schumer and SA Odrich, Am J Ophthalmol, 120, 528–530 (1995). PMID: 7573314. JS Lai and DS Lam, J Glaucoma, 8, 188–192(1999). PMID: 10376259. Y Eslami et al. Int Ophthalmol, 32, 449–454(2012). PMID: 22805881. S Jacob et al., J Ophthalmol, 2016, Article ID 2837562 (2016). PMID: 27144015.