- An intervention like cataract surgery can make an enormous difference to the life of a person with learning disability

- Clinics are often unprepared for such patients, resulting in suboptimal assessments and outcomes

- If told in advance of the referral, the clinic staff can make adjustments that are virtually cost-free

- These adjustments help people with learning disability to enjoy the enhanced quality of life that improved vision brings

Cataract surgery has improved the lives of millions worldwide, but the benefits for those with learning disabilities can be truly transformational. Although we can’t measure improvement on a Snellen chart, cataract surgery for patients with learning disability can change the lives of both patients and carers. One example is a patient who preoperatively was wheelchair-bound and needing two carers to assist with many activities of daily living including transfer on and off a toilet. The day after surgery she was running up and down the corridor unaided and being able to feed and dress herself, all because she can see what she is doing. People with learning disability can benefit in terms of independence and care requirements as a result of a cataract operation. Unfortunately, many patients with learning disabilities fail to receive the same level of eyecare as the general population. A commonly cited issue is poor communication. Firstly, patients with learning disabilities might not know or be able to communicate a change in vision and often changes in behavior are put down to a deterioration in their general health by carers and their health care teams. In the UK, as for any adult, it’s recommended that people with learning disabilities have their vision checked at least once every two years at a high street optometrist. The second communication is relevant from the ophthalmologist’s perspective: the patient’s learning disability is not mentioned in the referral or flagged up prior to their arrival in clinic.

Little changes, big results

Knowing the patient has a learning disability before they arrive in clinic is key to us being able to offer reasonable adjustments to patients and carers. The ophthalmologist is the last stop in the clinic and on occasions the patient has been overwhelmed by the new environment, encountering many different staff, being asked to perform a vision test which is inappropriate for them, and waiting times can be long. Problems can arise if patients and unfamiliar carers cannot tell us what their visual problems are or simply feel not confident in doing so. The worst hospital visit is one where we don’t give patients or carers the opportunity to show what is possible. This can happen if we have to make snap judgments on what we see within five or ten minutes in a clinic room. Hospitals are under pressure to see and discharge; to avoid bringing patients back for follow-up visits, and to make decisions about cataract surgery in a one-stop clinic. People with learning disabilities are not routine patients, and we need to change our approach for them.What can we do to improve the clinic experience?

If a patient’s learning disability status is flagged before the visit, we can prepare and adapt, making minor and virtually cost-free changes that can make sure their visit is a successful one. Most people with learning disabilities that I see have carers who know them very well, and know what they can and can’t cope with. If the carers tell me that the patient will struggle in noisy environments, we minimize any distress by offering somewhere quiet for them to wait. We can offer an appointment at the start of the clinic, before it gets too busy. We can split the assessment over more than one visit, perhaps checking vision the first time, and then going straight through to the ophthalmologist on the second visit. We can obtain their medical histories and establish what eye tests have been performed recently by optometrists or community opticians, to avoid needlessly repeating certain vision tests. When it is necessary to check vision, we can make sure that they receive a vision test that’s appropriate for their abilities with our orthoptic colleagues, using forced choice preferential looking tests or a functional visual assessment. (See "Frequent Concerns and Common Sense" below).The Royal College of Ophthalmologists have recently launched a Quality Standard Tool for Learning Disability Eye Care and departments can use this to guide provision of services.

http://top.txp.to/0514/rcophth

Such thoughtfulness is almost totally cost-free, but it makes a huge difference to the success of appointments and, ultimately, to the visual outcomes and quality of life of these patients. The city that I work in, Bradford, has a population of just over half a million people, of which around 2,400 have a learning disability, and those with visual disability comprise about a tenth of that. We actively assess the vision of adults with learning disability in the community to identify those with hidden sight loss, but even so we find that only a couple per month are referred into clinic. This is not an overwhelming number of patients to accommodate. We’ve worked with our day case unit and the local health facilitation team to overcome potential issues involved with pre and post-surgical care and many reasonable adjustments are possible to allow successful outcomes (See "Alternative visual assessment charts" below).

What have I learnt from my experience?

What counts is not extra money nor fancy equipment: the key to success is planning the visit and getting the most out of it. Finding out information before the patient attends and offering follow up visits for further discussion impacts positively on outcomes. The transformation that results from providing glasses, a low vision assessment or surgery can be absolutely astonishing for both the patient and their carer, and it is the most rewarding aspect of my job.Rachel Pilling is a consultant ophthalmologist at the Department of Ophthalmology, Bradford Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust, Bradford, UK

Frequent Concerns and Common Sense

How can I tell if a person with learning difficulties needs cataract surgery when I can’t test their vision?This a common question amongst ophthalmologists. Here, functional vision is important. Can the patient see the food on their plate? Are they able to see and pick up a glass of water? If they used to be able to do that, and can’t do that now, it is reasonable to surmise that cataract extraction may reestablish this prior level of vision. What about post-operative complications?

Many ophthalmologists are concerned that patients with learning disabilities are more prone to eye infections, are more likely to damage their eyes by rubbing, and generally more prone to complications. There is no real evidence for this. Preparation is all-important. Before for a patient undergoes cataract surgery, we give her or him a trial shield to take home, so the patient does not become as distressed when the shield appears after the surgery. How can we know that the patients will adhere to a four-a-day eyedrop regimen?

The community health care team can assist with drop desensitization to enable patients to tolerate post-op treatments. If this is unsuccessful, we can offer longer-acting formulations at the time of surgery and/or simply instilling drops when the patient is asleep.

Alternative visual assessment charts

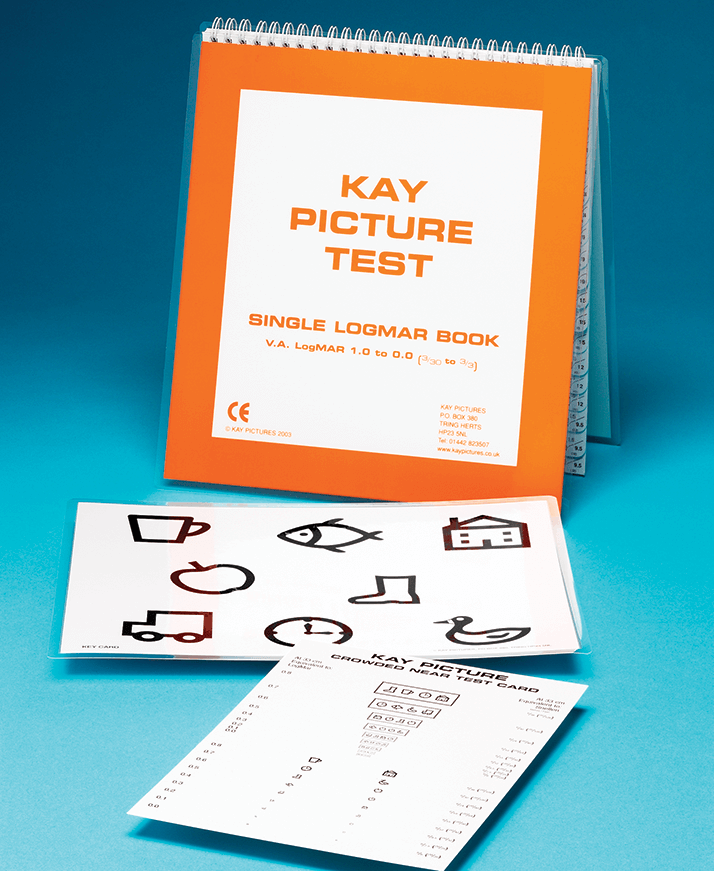

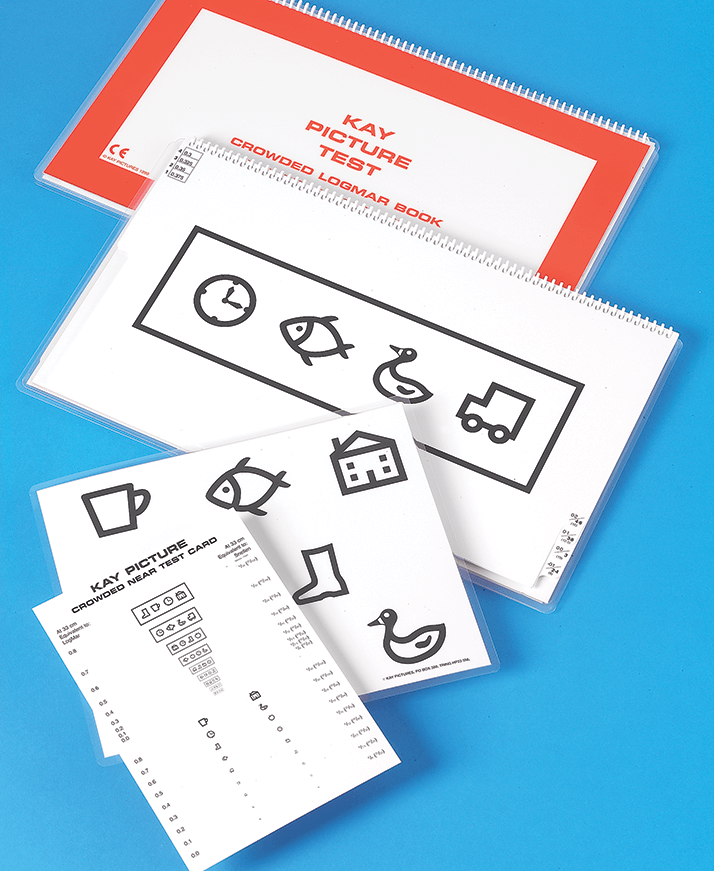

Letter charts like Snellen are absolutely fine for some patients, but for others they are a source of anxiety, leading these patients to actively avoid the eye clinic because they worry about getting it wrong. Here are some alternatives: Kay picturesA range of picture tests. Rather than read out a row of letters, the patient can read out symbols instead. They come in Snellen or LogMAR forms (Figure 1). The pictures are related to Makaton sign language – patients unable to speak may be able to sign to their carer what they see (Figure 2).

Cardiff cards

If the patients feel uncomfortable speaking or signing (Figure 3), Cardiff cards can be used. Typically they are used with pre-verb infants, but the same “preferential looking” principle applies to people with learning disabilities. By observing the patient’s eye movements you can determine if they can see the picture.

The Bradford Visual Function Box

This is a practical vision test. Patients are given beads of different sizes, ranging from 5 mm to 9 cm, and watched as they look at the beads. It is a simple test that provides a lot of information about the sizes of the objects that the patients can see. For children, it tells you what size of toy you need, and for older patients, it enables you to adjust their environment accordingly. For example, if the patient can only see something that’s 6 cm in size, then the food on their plate needs to be at least 6 cm big.