Peter Rainger, Chief Learning Officer at FundamentalVR, has a very personal reason for pushing the company’s involvement in ophthalmology (see final question). Here, he shares the story behind the technology and considers how VR could transform training for surgeons of all stripes.

What’s the FundamentalVR origin story in brief – and how did it get into the ophthalmic space?

Chris Scattergood and Richard Vincent started the company in 2014. They spotted an unmet need in the market for surgical simulations; the options at that time relied on expensive boxes that took up too much space and suffered high repair costs. Perhaps more importantly, they were not often useful to particular surgical specialties as there was insufficient variety among available simulations – and there was no option for easily growing the portfolio.

Early on, FundamentalVR brought in technologists from the virtual reality and gaming industries. We had a specific focus on haptics – the “technology of touch” – and developed a unique system: HapticVR; after all, users need to experience not only sights and sounds but also sensations for successful surgical skill acquisition, and in particular for building manual dexterity. Haptic cues are also helpful for physicians to practice clinical decision-making as they develop muscle memory, required for proficiency.

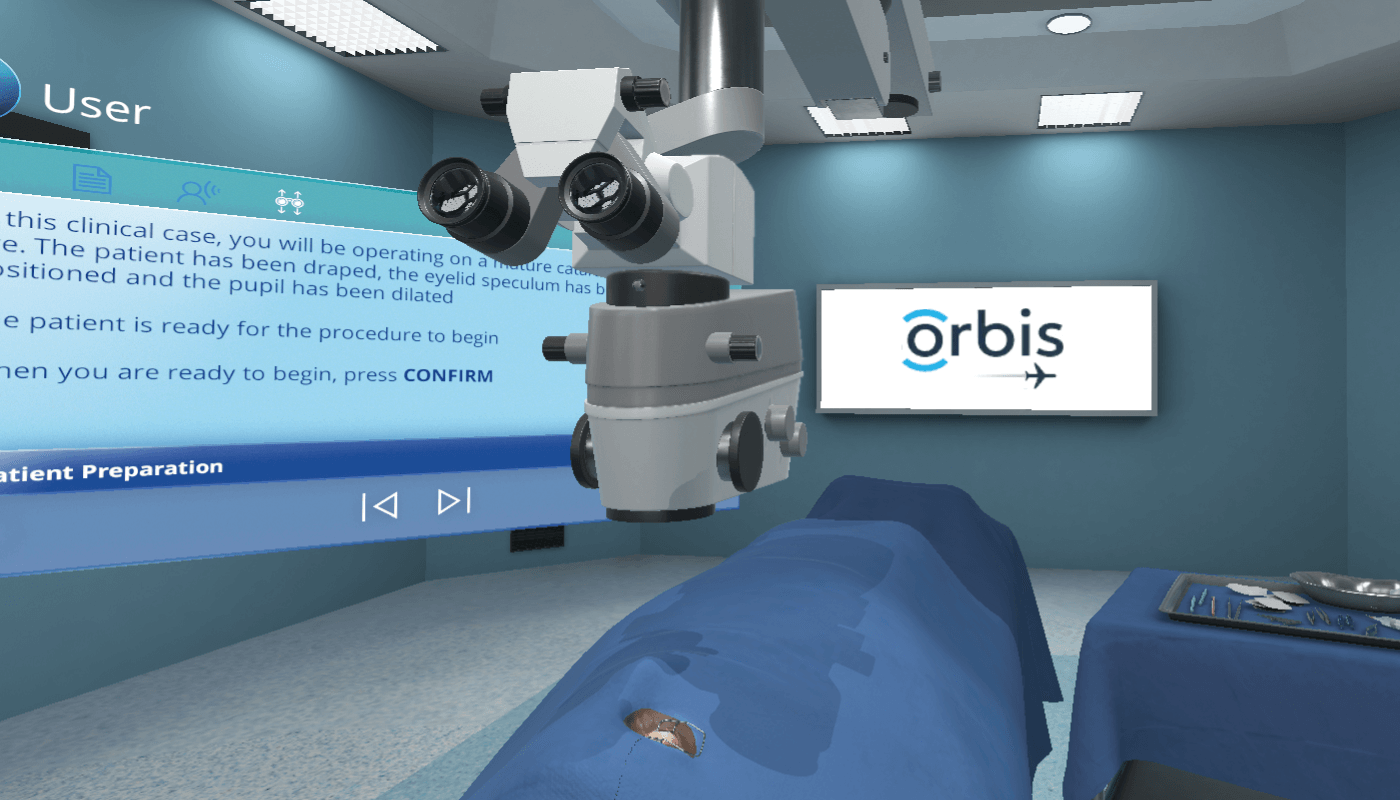

After originally focusing on orthopedics VR simulations, we started exploring other possibilities, landing on ophthalmology as one of the most exciting areas of precision medicine. It was also a great fit; the eye is highly complex and ophthalmic surgical procedures demand a great deal of training, but at the same time you’re working with a rather small, contained anatomy, which works really well for our simulations. When we started working with Orbis International, the global vision charity, we realized how much potential our technology had on a global scale. We are now exploring other opportunities in the ophthalmic space, with the help of our global medical panel. We are looking for possibilities to solve various ophthalmic training needs and scale this project up to support surgical trainees worldwide.

How did the partnership with Orbis start and what innovations have you developed together?

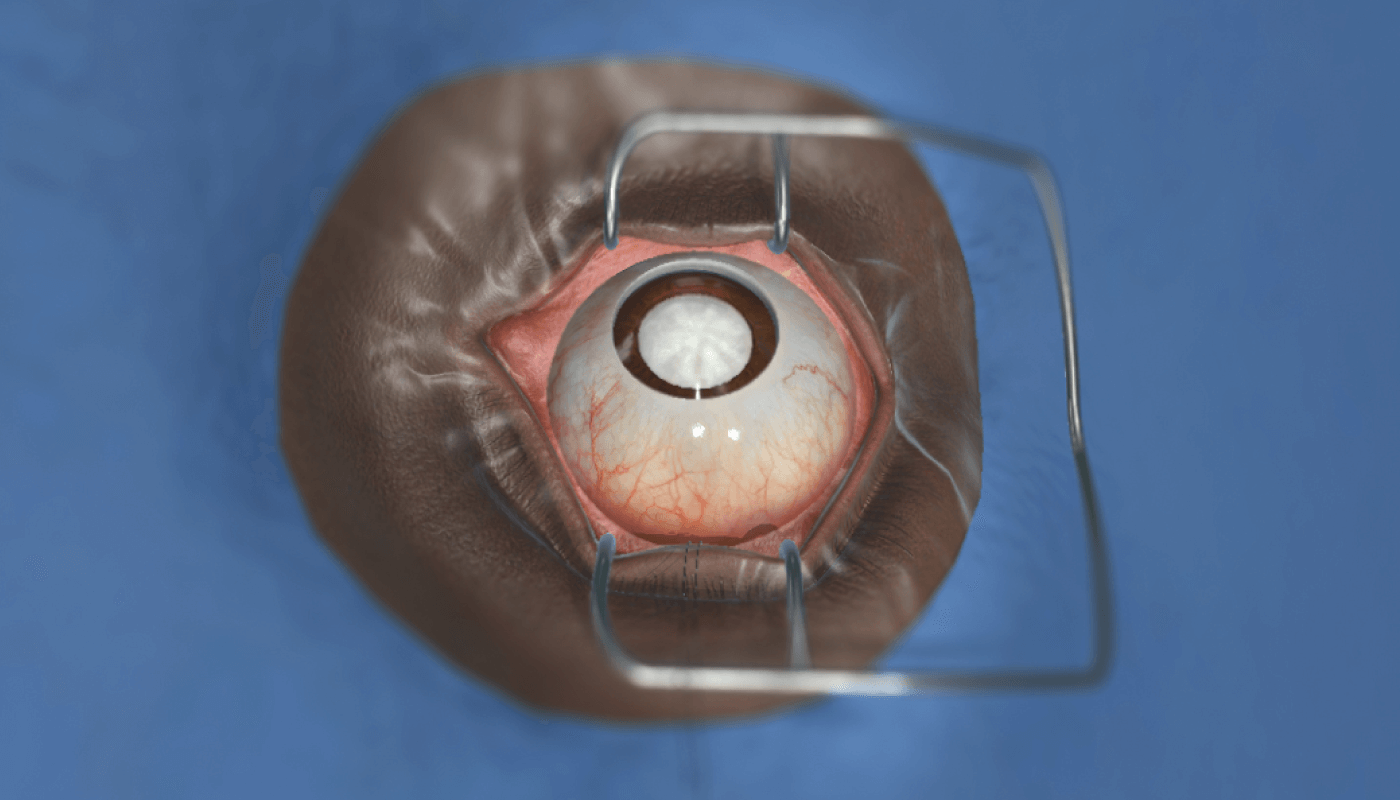

FundamentalVR approached Orbis to discuss working together just after the charity had outlined the need for a surgical simulation partner, so it happened to be perfect timing. As a result of the partnership, we recently created a cataract surgical simulator that Orbis is deploying for their cataract surgery residency training programs and training hubs. Manual small incision cataract surgery (MICS), a procedure that does not require a phaco machine, can be really useful for surgeons working in low- and middle-income countries, but without access to VR training, they might not otherwise have the means to practice the skill.

How does virtual reality compare with working on models or enucleated eyes?

It depends on the specific task and skill set required. Some pathologies are easier to model than others; some require different haptics or tissue modifications. But repeatability is certainly a big strength of virtual reality. You can also receive real-time feedback using objective measures, and focus specifically on the areas that need more deliberate, sustained practice. I can give you an example of an ophthalmic procedure we have been working on. It’s an improved retinal procedure simulation that has been evaluated by 12 retinal surgery experts around the world. They told us that – in their view – this training method works so well that they are looking at reducing the use of wet labs, and introducing virtual reality simulations.

We see virtual reality as part of blended learning. There is space to combine online learning materials, such as lectures, videos of surgical cases, and even some physical models with virtual reality simulation, which provides repetitive opportunity to practice skills and rehearse scenarios without the need for resources. Using proprioception and developing muscle memory is a key component to being a successful surgeon, and virtual reality, particularly when combined with sophisticated haptics, can help develop that in a three-dimensional environment.

Our technology can be applied anywhere in the world, which is a big advantage for remote locations and surgeons training to work among underserved populations.

It’s important to point out that technology is constantly changing and improving. The VR headset you tried on three years ago or a simulation you explored a year ago will be nothing like what you can experience now – or what it will be like in one or two more years’ time. We produce regular updates, using machine learning to analyze data from systems already in use, enhancing and improving simulations all the time. It’s a great benefit of using software as a service – you always have access to the latest technology.

And presumably the COVID-19 pandemic puts an attractive spin on VR?

Absolutely. Opportunities to observe and take part in real surgeries have been really limited in the past few months. We can provide a safe environment, without the need for classroom learning, meetings, and crowding operating rooms. Tissue-based wet lab training has been challenging to sustain since the COVID-19 pandemic started, so our system is a good alternative for ophthalmologists looking to hone their skills.

Before the pandemic, many people charged with training future surgeons saw simulation as useful, valuable and necessary, whereas now it is seen as an absolute necessity because of the lack of alternatives. People realize that, even when the current pandemic is over, the future is more uncertain than we’d imagined, and there is a need to invest in surgical simulations that can become a major aspect of training. COVID-19 has been a wake-up call for the industry; it became clear that the old ways of delivering training were not the most efficient ones. And other new benefits have come to light, such as standardization of techniques and practice, and setting clear patient safety records.

What’s in the future for VR surgery simulations?

As I hinted above, I can see industrialized countries adopting VR as part of core surgical training within five years. We’re planning to work closely with the industry to develop simulations for 10-20 percent of major procedures every year – an effort that can really help standardize surgical training in different parts of the world. The more embedded VR is in official residency programs, the more data we have to further improve training practices.

For low- and middle-income countries, the potential for using VR is huge – especially as equipment costs come down and as regular laptops are able to run simulations. We need a range of consumer-ready scalable hardware technologies for which companies like ours can develop simulation software, which is made available as a license to large numbers of users.

Eventually, I would like to see surgical residents in all specialties having easy access to a VR headset at home, and a haptic VR system at their hospital or clinic, so they can work on developing their skills in their own time.

As new generations of surgeons come through their medical training, they’ll be used to interactive and rich-media training elements. To them, VR might not have the same “wow” factor it might have for surgeons from previous generations, so it might be more natural for them to go straight to figuring out how this technology can help them hone their skills, learning from their mistakes in a safe way.

You mentioned the potential to level the playing field for residents from around the world…

That’s right. We can accurately and objectively measure trainees’ skills, which is the basis of a fair comparison. Using these metrics, we have the capability to compare residency programs around the world. Access to training and expertise can be improved, with the possibility of bringing experts and KOLs virtually into every classroom and allowing trainees to work with them as if they were in the same room. Charities, societies and organizations can help make that happen. Another vital element is access to collaborative communication platforms, where surgeons can exchange their tips and outcomes.

For residents who currently do not have access to virtual reality simulations, we have a resident group email, where you can find out more about the training we already offer. We have a special surgical residents’ advisory group as well as a global medical panel, with leaders across surgical specialties, including ophthalmology. Residents are encouraged to talk to institutions in charge of their training programs and ask them to check our portfolio of procedures, including the MICS simulation that we have recently released. There is also a clear role for industry to play in funding these simulations, so as to enable faster product adoption and use the precise measurement and auditable efficacy for data-driven compliance of their products.

Finally, there is a personal reason behind your passion for improving ophthalmic care, tell us about that...

When I was 16, starting to work towards my final exams, I developed blurry vision, which was diagnosed as uveitis. I then realized I had cataracts, which at that age can be a sign of other diseases, including tumors. It turned out I had an overactive immune system. My cataracts matured very quickly, so I was soon severely visually impaired. When my first cataract was removed, it appeared my retina had detached. In the five years from age 16 to 21 I went through multiple surgeries. When I was at university, I took the position of officer for students with disabilities, and I got involved in campaigns for improved care and healthcare research. I became very interested in how technology can help students with disabilities, and I helped set up a national group of access centers for students with visual and hearing impairments. Since then, I have been educating professionals in various areas of healthcare. It is great to think that now, working with ophthalmic trainees, I can indirectly help patients in the same situation I was in as a teenager. I still remember losing my vision twice, being told that there was no guarantee I would regain my eyesight, wondering what my place in society would be. Now, from a senior position in medical research, I can pay forward the amazing care I received.

https://fundamentalsurgery.com/