- No matter how far cataract and refractive technology has come – better IOLs, lasers and phaco platforms – surgeons still need to manage problems like inflammation, ocular surface disease and residual refractive error

- Both subjective (like pain and foreign body sensation) and objective (like inflammation and refractive error) issues can impact patient satisfaction after surgery

- Surgeons must seek to fully understand patients’ postoperative issues, then choose the simplest treatment that will alleviate the problem

- Prevention is better than cure though; to avoid dissatisfaction, surgeons must take time to consider what the most appropriate procedure will be for each individual patient at the outset

New lasers, lenses, inlays, SMILE… the technologies available for cataract and refractive surgery continuously advance. Patients are becoming increasingly educated and aware of their options – and their expectations continue to rise along with the possibilities. But perhaps all this talk of technology is a red herring. It’s still the surgeon who is central to these procedures, and it’s still the surgeon who is responsible for performing the surgery, managing patients’ postoperative care and ensuring their satisfaction. It’s certainly a responsibility we surgeons do not take lightly. Some of the results of the 2014 ASCRS Clinical Survey (1) on cataract and refractive surgery, therefore came as a bit of a surprise to me – most notably, that nearly a third of surgeons in the United States expected, as normal, cell and flare levels of grade 1 or higher one week postoperatively. Over a third believed that 0.75 D of residual sphere has no visual quality consequences; nearly half believed the same of 0.75 D or more of residual cylinder (and wouldn’t use laser vision correction to address even significant residual cylinder). But are these expectations on par with those of our patients, or should we be stepping up our game?

Surveying surgeons

On the positive side, those surgeons in the ASCRS survey stated that 38 percent of patients presenting for preoperative cataract and refractive surgery consults have ocular surface dysfunction or dry eye disease (DED) requiring treatment beyond just artificial tears. That’s good news because it’s important for surgeons to recognize that DED is a very common ocular disorder and can be a cause of blurred vision, it might also be a major contributor to visual impairment that wouldn’t be alleviated by the surgery – so the more often surgeons check for this in their patients, the better their chances of taking the right route to achieve patient satisfaction. But the other results are more disappointing. Forty-four percent of surgeons who participated in the ASCRS survey believe that leaving 0.75 D or more of residual cylinder has no visual quality consequences. But for those patients receiving multifocal intraocular lenses (IOLs) or other premium procedures, this is something that’s definitely not well tolerated. In cases where monofocal IOLs have been used in astigmatic patients, those with 0.75 D of residual cylinder may see beautifully. I’ve been surprised to see even patients with upwards of 1.5 D who still have great uncorrected visual acuity – but that’s certainly not the case for patients with against-the-rule astigmatism, which causes greater visual decline. And for every 0.25 D of residual cylinder in a multifocal patient, that patient’s quality of vision decreases by one line. Between that and surgeons’ belief that 0.75 D of residual spherical equivalent doesn’t significantly affect visual quality, it’s clear that we need to improve if we want to match our patients’ expectations.Visual acuity isn’t the only source of patient dissatisfaction, though it’s a major one. There can be other subjective complaints, like discomfort or foreign body sensation, objective issues, for instance, inflammation in the anterior chamber that’s greater than expected, or in some unfortunate cases, cystoid macular edema (CME). Patients might experience blurred vision from a residual refractive error, ocular surface disease, or an IOL malfunction. Finally, in some patients, multifocal IOLs work phenomenally well, but others simply can’t adapt to their new vision.

Patients in pain

In 2005, Fung et al. (2) surveyed 306 patients who underwent cataract surgery in the recovery room, assessing these patients’ pain and satisfaction levels immediately after surgery. Over a third reported mild to moderate postoperative pain, with most requiring oral analgesics. That’s a concerning statistic because postoperative pain is the most significant predictor of patients’ dissatisfaction with their care; patients who experience any pain at all tend to provide lower ratings of the quality of that surgical experience. I’d advise all surgeons to be mindful of that and do what they can to eliminate pain – control their technique and do what they can proactively to prevent CME and corneal edema. Obviously, anti-inflammatory drops after surgery can prevent the onset of pain, but we have to be careful with what we use (see Box 1); in general I find that generic drugs are often less effective than newer formulations, which are more potent and require less frequent dosing. Lower dosing frequencies align better with patient compliance and with ease of recovery in the postoperative period – and all of that is reflected in the patient’s ultimate happiness with their results.Box 1. Therapeutic options to prevent and control surgically-induced inflammation Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs):

- Stop formation of COX-1 and COX-2

- Prevent the enzymatic reaction that produces prostaglandins and thromboxanes

- Prevent pain and discomfort

- Prevent CME

- Routinely used as a preventative measure

- Once-daily dosing possible

Steroids:

- Interfere with the activity of phospholipase A2

- Inhibit the release of arachidonic acid and its metabolites, including prostaglandins

- Resolve anterior chamber cells and flare

- Not routinely used as a preventative measure, but can be

- Newer drugs are more potent and often require less frequent dosing

The difficulty of dry eye

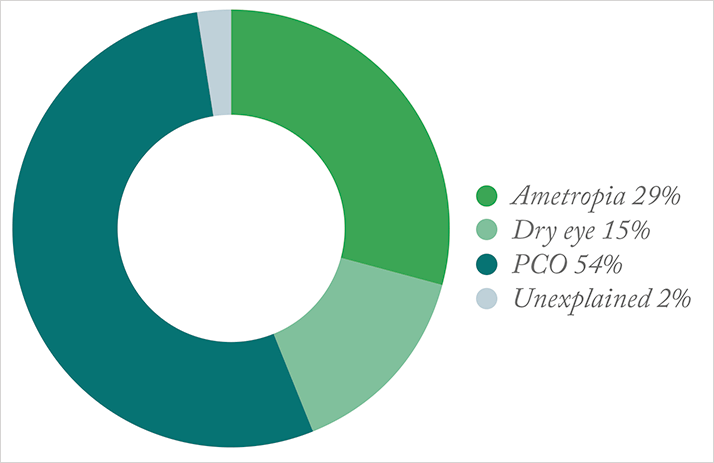

Ocular surface disease – and in particular DED – is a tougher problem to tackle. Surgically-induced DED occurs in about 30 percent of patients who undergo cataract surgery, but its etiology is unclear; it’s been associated with numerous causes (see Box 2). But regardless of its origins, we know that dry eye is a very frequent cause of postoperative dissatisfaction, especially in patients implanted with multifocal IOLs (Figure 1).Box 2. Causes of surgically-induced DED

- Decreased goblet cell density

- Highly grooved incisions creating contour differences that impact upon tear film coverage

- Preservatives in topical medications

- Toxicity of topical medications

- Higher intraoperative times

To fully understand a patient’s DED, we have to combine their symptomatology with our clinical findings. That means asking about the timing and quality of the pain. Does it occur first thing in the morning or as the day wears on? Is it achy or sharp? Is the irritation constant? Does it increase with blinking? We also need to ask about blurred vision – is it constant, or does it fluctuate? A fluctuation in the visual quality would be more suggestive of an ocular surface problem, whereas a constant blur would point to a refractive or lens-based issue. Asking questions like these helps us to zero in on the most significant causes of the patient’s DED.

To address the problem, we generally start by minimizing medication toxicity. If the patient is using a generic anti-inflammatory, I recommend changing it to a branded one; if you’ve prescribed drug formulations that contain preservatives, switch to preservative-free alternatives. After that, treatment depends on what we’ve identified as the root causes. We have all sorts of ergonomic options – adding a mini humidifier, assessing and changing how people interact with their computer, phone or tablet, or offering more intensive dry eye therapies like long-term medications, punctal plugs, or surgery. No matter what approach each patient needs, we have to prioritize treating all DED, because that in itself can lead to refractive error, and can certainly sow the seeds of patient dissatisfaction.

Addressing residual refractive error

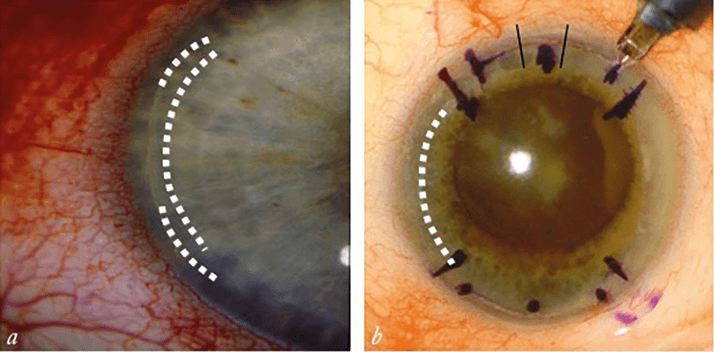

Residual mixed astigmatism can also impact patients’ happiness. When undercorrected astigmatism is a source of refractive error, I prefer to wait at least three to four weeks before taking any steps to address it. That way, the patient is off their medication and I can get a clear idea of their refraction, and then I can either lengthen an existing limbal relaxing incision (LRI; see Figure 2a) or place an additional, more central incision. There’s a third option – I could also place an incision at 180° to the existing ones, particularly if there was only a single LRI to begin with. Overcorrected astigmatism is a bit trickier. Again, I wait several months to ensure the patient has fully healed and is off all medications. In some cases, I try using a therapeutic bandage contact lens to heal gaping LRIs, but in others, I simply suture them. I try to avoid needing to place an LRI in the opposite axis to counteract the initial overcorrection – but sometimes that ends up being necessary (see Figure 2b).

When correcting astigmatism, you need to ask yourself: do you place an LRI, or do you take a different approach like an IOL change or laser vision correction? The answer will be different for each patient, depending on the degree of residual astigmatism and the patient’s refractive error. Patients with a diopter or less of mixed astigmatism can be treated with an LRI, but patients who have more than one diopter or a residual refractive spherical equivalent error sometimes can’t be fixed with an LRI alone – in cases like that, you may want to use a phoropter to show your patient the difference between correcting the only the astigmatism versus the total refractive error. That way they can help you decide whether to use an LRI or laser vision correction. Choosing laser vision correction adds complexity. If you take that route, a standard laser treatment is often sufficient; I caution against doing a wavefront-guided or customized laser treatment pattern, particularly for patients with multifocal IOLs. As with any other procedure, you should wait several months after the initial surgery, and then do a YAG capsulotomy before any kind of laser vision correction. That way, if the patient was seeing well initially and then something happened that affected their sight, you can get them back to their immediate postoperative vision with the proper ocular surface treatment. Proceed with caution, though – if the patient wasn’t satisfied immediately after surgery, I would recommend that you don’t do the YAG capsulotomy, as that patient may require an IOL exchange. Obviously, that’s not the ideal end result – you can try soft contact lenses or spectacle correction for small refractive errors, or lens rotations in the case of a toric IOL – but if all else fails, then your final option is an IOL exchange.

As surgeons, we need to choose our advanced technology patients wisely. It’s important to pay attention to preoperative checklists to ensure that each patient receives the right lens, and to make sure that they are satisfied with their first eye before we treat the second. At the end of the day, we can’t make everyone happy immediately – but if we take our time and respond appropriately to dissatisfaction, then refractive cataract surgery can give great satisfaction even in patients who are initially unhappy.

References

- American Society of Cataract and Refractive Surgery, “ASCRS Clinical Survey 2014”, (2014). Available at: http://bit.ly/1aa7gCi. Accessed October 19, 2015. D Fung, et al., “What determines patient satisfaction with cataract care under topical local anesthesia and monitored sedation in a community hospital setting?”, Anesth Analg, 100, 1644–1650 (2005). PMID: 15920189. MA Woodward, et al., “Dissatisfaction after multifocal intraocular lens implantation”, J Cataract Refract Surg, 35, 992–997 (2009). PMID: 19465282.