One of the most debilitating microvascular complications of diabetes is diabetic retinopathy, the most important cause of blindness among working age adults in developed countries. Diabetic patients´ blood vessels suffer two abnormal processes: vascular incompetence and vascular occlusion. The first leads to leakage of blood and blood products into the retina, while the second leads to patches of ischemia in the retinal capillary bed and to neovascularization. In these patients, vision loss is generally associated with diabetic macular edema (DME), defined by macular abnormal collection of extra-capillary fluid due to blood-retinal barrier breakdown because of increased production of inflammatory mediators and vascular permeability factors and loss of endothelial tight junctions (1–3). This article presents a case report of a patient with recurrent DME uncontrolled by several medical and surgical treatments.

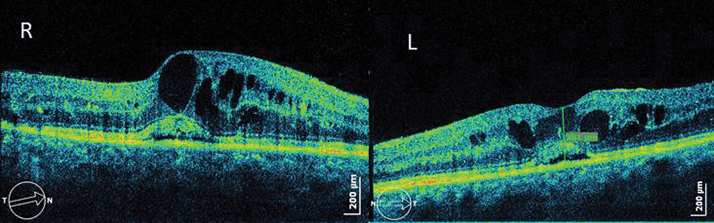

Case presentation The patient was a 59-year-old Caucasian female, who demonstrated good metabolic control (6-7.5% HbA1c) of type 2 diabetes over the last 25 years. She was first seen in November 2004 with bilateral incipient diabetic retinopathy. Management and outcome Almost four years after first presenting, she developed cystoid macular edema (CME) and decreased vision (3/10 in the right eye, 4/10 in the left eye) and she was treated with focal laser argon grid in both eyes. Her best corrected visual acuity (BCVA) and CME did not improve (Figure 1) and so the patient was treated with intravitreal injection of corticosteroids in both eyes (triamcinolone) and started pan-photocoagulation therapy in the left eye because of proliferative diabetic retinopathy.

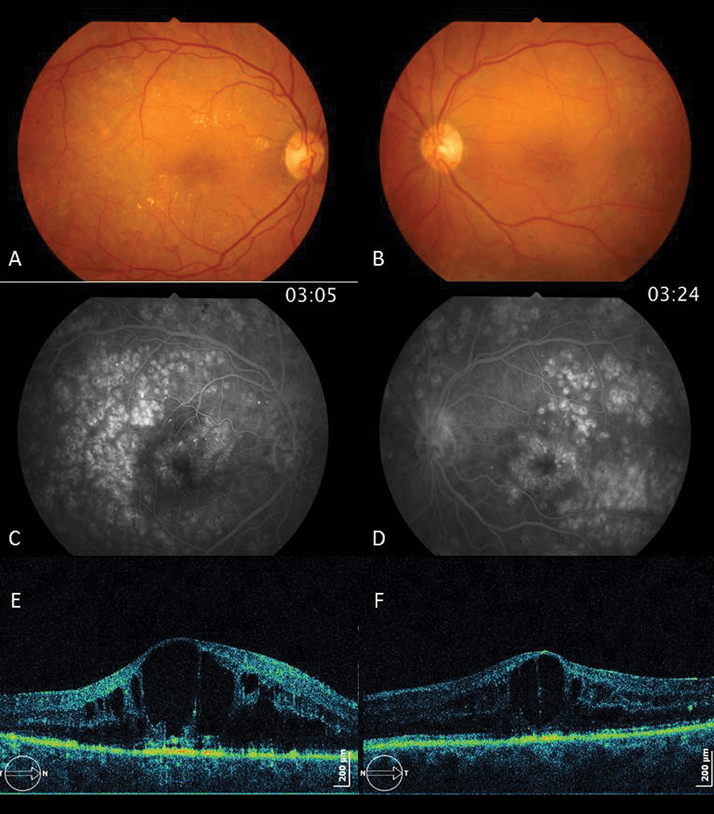

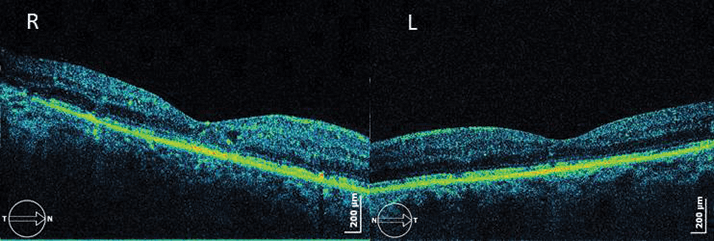

In December 2010, she showed improved anatomical aspects, with minimal focal CME in the right eye and without CME evident in the left eye, but BCVA increased to only 4/10 (right eye) and 5/10 (left eye). Despite good glycemic control, the patient´s CME and proliferative retinopathy continued to develop and BCVA started to drop, so she was administered three intravitreal injections of ranibizumab into the right eye, to which she did not respond. In August 2011 (Figure 2), the patient’s CME increased and BCVA decreased again (4/10 (right eye) and 1/10 (left eye)). She was injected with corticosteroids in both eyes and, although an anatomical improvement was noted (Figure 3), her BCVA did not improve in the left eye (4/10 (right eye) and 1/10 (left eye)).

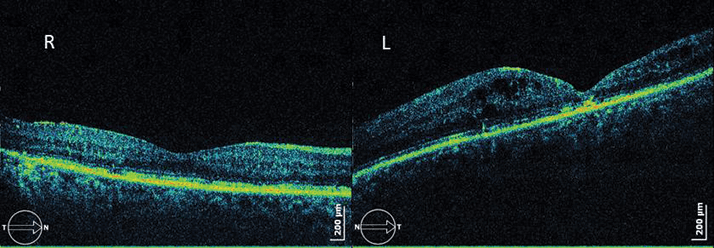

Almost six months later, CME recurred and vision dropped to 1/10 in the right eye and 0.5/10 in the left, and so another intravitreal corticosteroid was administered. Intraocular pressure (IOP) rose to 26 mmHg in both eyes as a result and it was treated with a topical combination of timolol and dorzolamide. BCVA rose to 5/10 in the right eye but decreased in the left because it developed cataract and vitreous hemorrhage. It was therefore necessary to perform a pars plana vitrectomy (PPV) without internal limiting membrane (ILM) peeling combined with phacoemulsification in November 2012. Despite this surgical procedure to the left eye and the good anatomical result, BCVA never recovered (it stayed under 0.5/10). The patient underwent phacoemulsification combined with intravitreal corticosteroid (right eye) because she developed cataract and CME. BCVA increased to 6/10 and the macula became dry (Figure 4).

In September 2013, the right eye developed CME and the BCVA dropped to 2/10. The patient received a new loading dose of three intravitreal ranibizumab injections and BCVA reached 5/10 again, but four months later CME recurred. We now plan to administer a new intravitreal corticosteroid. The future is still unknown! Discussion Despite good glycemic control, this patient saw her clinical situation worsen even though all possible surgical and most modern therapeutics were used to battle her DME. It is difficult to know what went wrong. Firstly, patient metabolic control was always good and all the others risk factors were under strict surveillance. The only known risk factor was her diabetes (and its long duration). Secondly, the patient´s treatment followed all standard procedures available to us at the time; on initial presentation, intravitreal anti-VEGF agents and corticosteroids were only just becoming available. Thirdly, anatomic aspects of CME in optical coherence tomography (OCT) presented poor prognostic signs, such as subfoveal neurossensorial retinal detachment associated with enormous intra-retinal cysts. There is a chance that levels of inflammatory mediators and vascular permeability factors were so high they resulted in huge retinal changes. Finally, PPV was performed with peeling of posterior hyaloids membrane and not of ILM. We are still uncertain of the role of PPV in the management of DME and proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Specifically, we don’t know if ILM peeling is beneficial to the final visual outcome. Conclusion Combined medical and even surgical procedures may be the best pathway to achieve DME control in patients. This patient is a challenge to any ophthalmologist that treats DME because almost all complications of diabetic retinopathy and therapy-induced adverse events were observed. It is necessary to be prepared to deal with all of these adversities and to continue moving forward with different treatment options until a solution is found. Statement: Full consent was provided by the patient

References

- N. Bhagat, R.A. Grigorian, A. Tutela,et al., “Diabetic macular edema: pathogenesis and treatment”, Surv. Ophthalmol. 54(1), 1–32 (2009). Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network, “A randomizes trial comparing intravitreal triamcinolone acetonide and focal/grid photocoagulation for diabetic macular edema”, Ophthalmol. 11589, 1447–1149 (2008). Q.D. Nguyen, S. Tatlipinar, S.M. Shah, et al., “Vascular endothelial growth factor is a critical stimulus for diabetic macular edema”, Am. J. Ophthalmol. 142(6), 961–969 (2006).