Limbal stem cell deficiency (LSCD) arises from many etiologies, including traumatic or toxic (e.g. contact lenses, chemical/thermal injuries), inflammatory (Stevens-Johnson syndrome, mucous membrane pemphigoid, chronic allergic diseases), and congenital (aniridia). Clinical manifestations include corneal conjunctivalization, non-healing epithelial defects, neovascularization, scarring, and severe pain and loss of vision (1). In all cases, irrespective of etiology, a key feature is the loss of the limbal niche. Currently, LCSD is managed by surgical transplantation procedures including conjunctival limbal autograft (CLAU), cultivated limbal epithelial transplantation (CLET) and simple limbal epithelial transplantation (SLET). These cutting-edge techniques are more appropriate for unilateral disease. For bilateral cases of LCSD, limbal allograft techniques prevail. We propose that all LSCD treatments should focus on rebuilding the limbal niche to restore stem cell function, and we believe that mesenchymal stem/stromal cells (MSCs) are a promising solution.

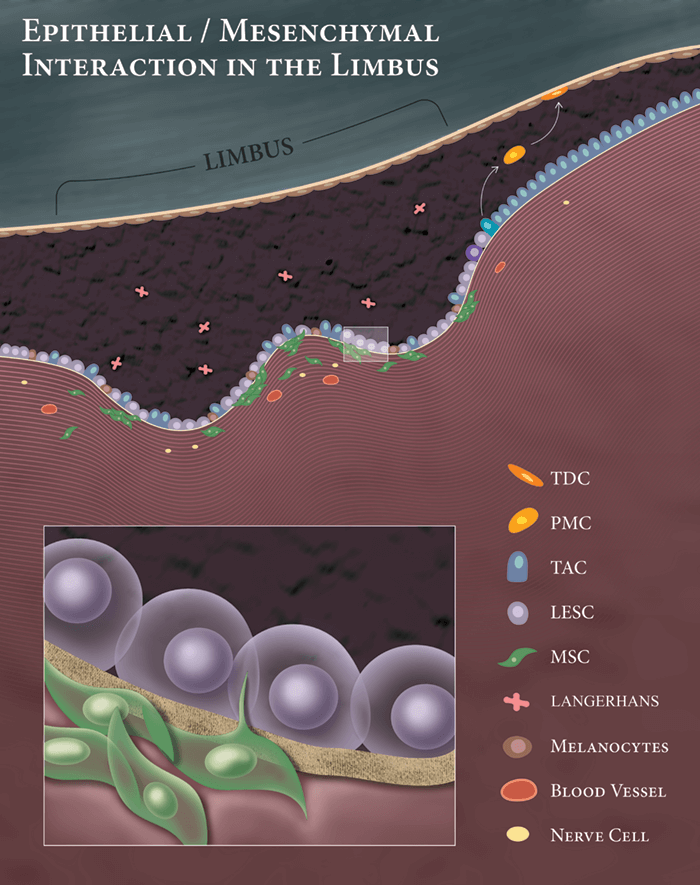

Limbal epithelial stem cells (LESCs) reside in the Palisades of Vogt, where they closely interact with extracellular matrix components, melanocytes, immune cells, blood vessels, nerves and MSCs. Of these, MSCs have a major regulatory role in niche biology, and help maintain the ‘stemness’ of the LESCs (2)(3). Given their critical function, MSCs are ideally positioned for “niche regeneration”; they secrete various growth factors and cytokines that promote epithelialization and wound healing, and exhibit anti-inflammatory anti-scarring, anti-angiogenic and neurotrophic properties (3). Different experimental models have shown MSC transplantation successfully reconstructs damaged corneal surface; they promote wound healing by differentiation, proliferation, and secretion of trophic factors to revitalize remaining LESCs. This ability to support regeneration of the damaged ocular surface has been shown for MSCs isolated from various tissues (cornea, bone marrow, adipose tissue, umbilical cord and perinatal), and thus appears to be a general property of these cells. Inflammation is also a major cause of niche disturbance in LSCD. MSCs can modulate both innate (neutrophils and macrophages) and adaptive immune cells (including T cells, B cells and natural killer cells). These immunomodulatory properties of MSCs suppress local inflammation, protecting LESCs in their niche. We have recently shown MSCs directly inhibit corneal neovascularization, and modulate infiltrated inflammatory macrophages toward an anti-inflammatory anti-angiogenic immunophenotype, which further potentiates MSC properties (4)(5).

Currently, there are several clinical trials evaluating MSCs. A recent randomized clinical trial compared MSC-therapy with CLET, and found that both procedures were equally effective at restoring corneal epithelial function (6). The authors concluded that, as LSCD treatment with MSCs is more efficient than CLET in terms of patient morbidity, time- and resource-consumption, and economic expenditure, MSC translation into clinical practice should be pursued. We believe that MSCs may provide a distinct strategy for restoring the health of the limbal niche, without the need for costly procedures, such as CLET, or invasive surgery. Future clinical studies are needed to further define their precise role in the management of severe ocular surface disease, but we hope to see MSC-mediated therapy for LCSD enter the clinic one day.

References

- EJ Holland. Cornea, Cornea, 34, Suppl 10 S9–S15 (2015). PMID: 26203759. MA Dziasko and JT Daniels. Ocular Surf, 14, 322–330 (2016). PMID: 27151422. N Polisetti et al., Mol 16, 1227–1240 (2010). PMID: 20664697. M Eslani et al., Stem Cells, 36, 775–784 (2018). PMID: 29341332. M Eslani et al., IOVS, 58, 5507–5517 (2017). M Calonge et al., IOVS,58, 3371 (2017).