Until very recently, community optometrists followed the 2010 guidance issued by the Royal College of Ophthalmologists: refer any patient with ocular hypertension – meaning IOP over 21 mmHg – to a glaucoma clinic, even if no other risk factors are present. Unfortunately, this advice resulted in a ~35 percent increase in referrals without increasing glaucoma diagnoses. A high proportion of these “glaucoma suspects” required monitoring for five years; so it is unsurprising that, by 2015, glaucoma and suspected glaucoma together accounted for the sixth largest share of NHS outpatient attendances.

It’s easy to understand why we relied on IOP for screening: it’s the major known, modifiable risk factor for POAG, its measurement is straightforward, and it is presented in the form of a number that requires no expert interpretation. The warning signals regarding over-reliance on IOP, however, have been evident for decades; around half of those presenting with POAG have IOP below 21 mmHg, and many of those with IOP over 21 mmHg never develop glaucoma. But changing an established screening system for an important, sight-threatening disease cannot happen overnight – it requires a lot of hard data.

We set about collecting this data in the EPIC Norfolk Eye Study, a community cross-sectional study where nearly 9000 participants were recruited in Norfolk and underwent detailed eye examination between 2004-2011. (see box: What does high IOP really mean?) Historically, the figure 21 mmHg was derived from a 1966 study, and corresponds to two standard deviations above a population’s mean IOP (1). Our aims, in brief, were to re-examine the 21 mmHg IOP referral threshold by measuring the distribution of IOP in this UK population. We also wanted to assess the potential consequences of changing the referral threshold: how might such changes affect referral numbers and diagnosis rates?

The EPIC-Norfolk Eye Study looked at the link between IOP and glaucoma in nearly 9,000 patients over 7 years (2004–2011).

Design:

- Community-based, cross-sectional observational study

Population:

- 8,623 subjects, aged 48-92, 99.4 percent white, 55 percent female

Aims:

- Assess IOP and glaucoma prevalence by age and sex

Methods:

- Subjects underwent ocular examination to measure IOP and identify glaucoma:

- IOP measured with Reichert Ocular Response Analyzer (ORA) non-contact tonometer for most, and a small subset with Reichert AT555 non-contact tonometer

- Glaucoma status determined by a systematic ocular exam to detect characteristic structural optic disc and visual field changes

Results:

- IOP measured in 8,401 participants, 243 of whom used ocular hypotensive eyedrops:

- 10 percent had ocular hypertension (IOP>21 mmHg)

- 4 percent had glaucoma; of these, 87 percent had POAG and 67 percent had already been diagnosed with glaucoma

- 76 percent of patients with newly diagnosed POAG (83/107) had IOP below 21 mmHg

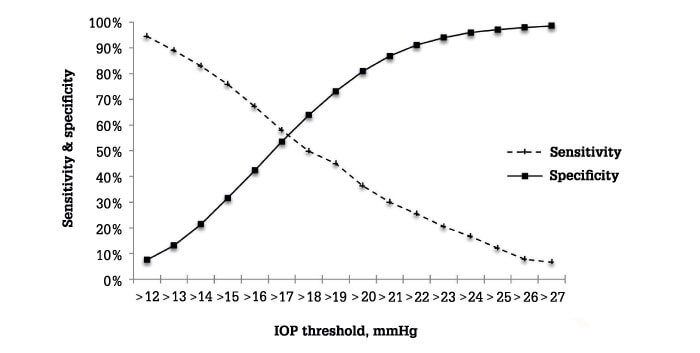

- No single IOP threshold provided adequately high sensitivity and specificity for the diagnosis of glaucoma (see graph)

- The upper limit of IOP distribution (mean +2 standard deviations) for participants without glaucoma is 24 mmHg

Conclusion:

- IOP alone is a poor screening tool for glaucoma

Our study (2) confirmed the views of many who work in the field: there is no IOP cut-off value that is sufficiently sensitive and specific to distinguish between those who have optic nerve damage and those who do not.

In fact, in our study population, 76 percent of patients newly found to have glaucoma had IOP below 21 mmHg, and therefore would have been missed by the standard screen. Furthermore, 10 percent of those without glaucoma had IOP in excess of 21 mmHg, suggesting the potential for over-diagnosis and unnecessary treatment. Overall, many normal eyes have pressures over 21 mmHg, and many glaucomatous eyes had pressures below 21 mmHg (Figure 1).

Using these data, we modeled the impact of different IOP thresholds on potential referral numbers, and showed that even modest increases – from 21 to 22 or 23 mmHg – could lead to referral reductions of up to 31 and 52 percent, respectively, while raising the threshold to 24 mmHg could cut referrals by up to a massive 67 percent. The great majority of these reductions represent false positives, because the specificity of glaucoma case-finding improves with higher IOP thresholds.

Therefore, increasing the threshold will have only a relatively small negative impact in terms of missed diagnoses. Further, we found that the risk of undiagnosed glaucoma correlated with a lower optic cup/disc ratio, such that optic disc changes appear less severe. Our recommendation therefore was that careful optic disc screening should be a key part of glaucoma screening, and should be emphasized in the training of all eye care professionals. Attention in this area should decrease the frequency of missed diagnoses.

Our overall conclusion was that relying on IOP alone for glaucoma screening was not a viable strategy. This finding transformed glaucoma care in the UK: in November 2017, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) raised the glaucoma referral threshold from 21 to 24 mmHg. There is little doubt that this new guidance will reduce false referrals and save NHS resources.

Looking ahead, one of our other findings – that lower corneal hysteresis and higher corneal-compensated IOP (IOPcc) is more closely correlated with POAG than is higher Goldmann-corrected IOP (IOPg) – suggests new metrics to include in future glaucoma screening programs. Other factors to take into account could include demographic information (glaucoma is more common in older people and in those of African ethnicity); family history (having a first degree relative with glaucoma is a significant risk factor). This comprehensive approach would mitigate against any increased risk of undiagnosed cases resulting from increasing the IOP referral threshold.

In summary, careful analysis of large datasets, and sensible adoption of the resulting recommendations, can bring about radical cost-savings and improvements to care.

References

- FC Hollows, PA Graham, “Intra-ocular pressure, glaucoma, and glaucoma suspects in a defined population”, Br J Ophthalmol, 50, 1570 (1996). PMID: 5954089.

- M Chan et al., “Glaucoma and intraocular pressure in EPIC-Norfolk Eye Study: cross sectional study”, BMJ, 358, j3889 (2017). PMID: 28903935.