- Internet research by patients may lead them to have unreasonable expectations of treatment efficacy

- Not all patients are equal; concomitant diseases can affect their treatment outcomes and options

- Understanding what factors make a difference means you can manage patient expectations, and optimise the therapeutic regimens prescribed

“Doctor Google” provides unlimited information on almost any disease to patients and their families, so it comes as no surprise when patients, having cherry-picked from the web, have unrealistic expectations of how successful their treatment will be. Partly, this is due to marketing messages that are scattered across the web, but even publications containing well-designed clinical trial manuscripts can mislead avid patient Googlers. This is not because of any nefarious practices on the part of the researchers or the journal; rather, it’s often a failure of patients to notice the finer details of the patient population (inclusion and exclusion criteria, proportions of different patient types) within each trial.

Many patients may have poorer outcomes than the clinical trial cohort because they differ from the trial population – primarily by disease morphology. One particular misunderstanding that some patients have is the concept of average; clinical trials show average or median result data, and that’s what they expect to experience. However, every practicing ophthalmologist will see a vast range of treatment responses – few patients have an “average” response. Clinical trial data are not easily transferrable to the individual patient. This is important not just for managing patient expectations, but for the physician too. It is often crucial for determining the best therapeutic options, in terms of drug choice, dose and regimen, so that the patient achieves the best possible outcomes.

The AMD experience

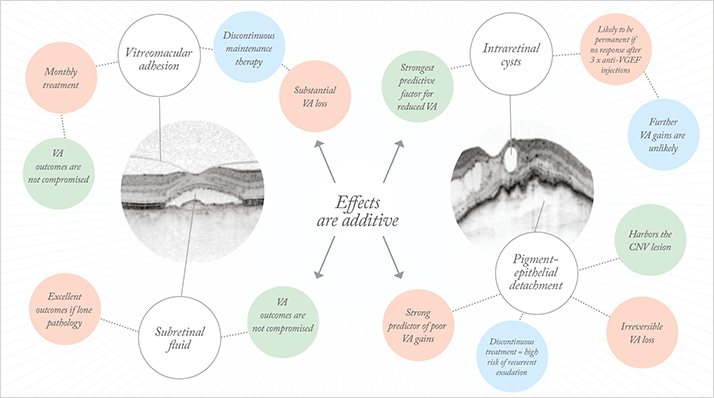

In patients with neovascular age-related macular degeneration (AMD) there can be large disparities between the drug dosing regimens employed in the clinical trials (mostly fixed monthly or bimonthly administration) and real-world settings (where as-needed or treat-and-extend is mostly used). Timely management of patient expectations is necessary to ensure that they are satisfied with treatment outcomes. Moreover, adequate and realistic guidance for the choice of dosing regimen is essential for the treating ophthalmologist. Today, we are seeing analyses of individual lesion subgroups from within large-scale clinical trial populations beginning to be published. This is useful as it offers insight into the disease-specific mechanisms that can alter patient outcomes, and allows personalized choice of treatment as well as prognosis and counseling of patients prior to the procedure. Our research group led by Ursula Schmidt-Erfurth has performed in-depth subgroup analyses of multiple multicenter trials. These trials enrolled more than 1500 patients, who received standard therapeutic regimens of European Medicines Agency (EMA)-approved drugs, using various dosing regimens. What follows is a brief overview of our findings (see Figure 1).Intraretinal cysts

Intraretinal cysts (IRCs) at the time of presentation are a strongly negative predictor of visual function. They presage a mean reduction in visual acuity (VA) of about 1 line, and a below-average improvement in vision during therapy. Having said that, once anti-VEGF treatment has been initiated, over one half of all patients experience IRC resolution.

IRCs provide a classic example of the consequences of exudate entering neurosensory tissue, a sign of advanced disease. Choroidal neovascularization (CNV) typically develops below the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) and subsequently invades the retina (Type I CNV). In patients who present with neovascular AMD and IRC irreversible damage has already happened, and anti-VEGF therapy will be substantially less effective than if it were administered at an earlier point during the progression of the disease.

Pigment epithelial detachment

VA gains with anti-VEGF therapy will be lower in patients presenting with pigment epithelial detachment (PED) than patients without. The reduction in VA gain is only half as bad as with IRC, but these effects are additive; a patient presenting with both will have particularly poor outcomes. Clinical trial data have shown that patients with PED and otherwise dry retina are particularly at risk of significant VA loss if placed on a reactive, discontinuous anti-VEGF treatment regimen.

Fibrovascular PED harbors the CNV lesions in the majority of patients (that is, Type I “occult” CNV). Intensive anti-VEGF treatment results in pronounced PED flattening. However, if the retina is otherwise dry and treatment is discontinued, the CNV lesion will reactivate and grow underneath the RPE as VEGF suppression declines – in other words the PED starts to expand again. However, PEDs usually develop rather slowly and it is not regarded as an indication for treatment in most clinical environments. Treatment is re-administered only if the RPE is breached and intra- and/or subretinal exudation occurs. In these cases, it is likely to be too late to prevent irreversible photoreceptor loss and neurosensory damage.

Subretinal fluid

The presence of subretinal fluid (SRF) is of limited prognostic value; patients with neovascular AMD and SRF alone typically exhibit excellent visual outcomes, with vision gains in the range of two or more lines, when treated with anti-VEGF therapy.

Vitreomacular adhesion

The status of the vitreomacular interface is one of the most difficult pathologies to interpret because vitreous configurations, which encompasses vitreomacular adhesion (VMA) and posterior vitreous detachment (PVD) may change over time and one may develop one into the other (see “Loss of Traction”).

General recommendations for ophthalmologists

The following steps should be followed for prognosis of AMD after treatment with anti-VEGF agents and managing patient expectations:- Ascertain the state of the retina using optical coherence tomography (OCT) imaging, to determine the pathology or pathologies.

- For patients who present with IRC – and particularly those with IRC still present after three doses of anti-VEGF – advise that their vision gains are likely to be substantially lower compared with other patients.

- If a decision is made to employ a discontinuous treatment regimen for patients with PED and/ or VMA, follow up monthly with OCT-based assessment of their disease status.

- If a growing PED in a patient with neovascular AMD is observed, this should prompt retreatment, even if the retina is otherwise dry.

It is important to manage both your own and your patients’ expectations when undertaking a course of anti-VEGF therapy – partly for the patients’ own peace of mind, and partly for your own reputation and treatment planning. To achieve these twin goals, determine the best therapeutic regimen before commencing treatment and give your patients an honest assessment of what their vision is likely be after anti-VEGF therapy.

Sebastian Waldstein, is the Laboratory Coordinator at the Christian Doppler Laboratory of Ophthalmic Image Analysis at the Vienna Reading Center, Department of Ophthalmology, Medical University of Vienna, Austria.

References

- 1. U Mayr-Sponer, SM Waldstein, M Kundi, et al., “Influence of the Vitreomacular Interface on Outcomes of Ranibizumab Therapy in Neovascular Age-related Macular Degeneration”, Ophthalmology 2013 [Epub ahead of print]