- Childhood glaucoma requires early diagnosis and treatment

- “Western” glaucoma is typically less severe than “Eastern”

- Diagnosis is challenging, often requiring the patient to be sedated

- Surgery is almost always the answer; drugs need to be used sparingly

Glaucoma is exceeded only by cataracts as a cause of blindness. In 2002, the World Health Organization estimated that 12.3 million people worldwide had been blinded by glaucoma. The disease occurs when intraocular pressure (IOP) rises above a level that damages the optic nerve, leading to visual field defects and eventually, if left uncorrected, blindness. In children, undetected – and therefore untreated – glaucoma raises the tragic prospect of lifelong blindness. Early glaucoma detection is important for people of all ages, but is absolutely critical – and particularly challenging to perform – in pediatric cases.

Childhood glaucoma comes in a number of forms. Present at birth, it is “congenital glaucoma”; if it develops before a child’s third birthday, it is “infantile glaucoma”. In both cases, there are morphologic changes in the anterior and posterior segments of the eye. Typically, when glaucoma develops after the age of three, the morphologic changes occur only in the posterior segment of the eye – optic nerve cupping – and it is referred to as “juvenile glaucoma”. A couple of nuances exist in the terminology: if no other ocular or systemic diseases are present, this is referred to as “primary” glaucoma, whereas the prefix “secondary” is used if a congenital ocular, or acquired ocular or systemic disease has caused the glaucoma.

East versus West

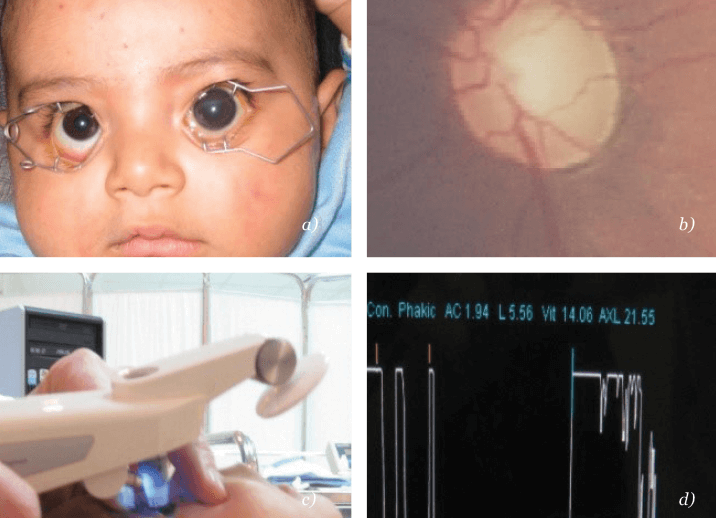

Pediatric glaucoma is rare in the Western world, where the incidence is estimated at 1 in 10,000 live births. It is far more common in the pediatric age group elsewhere, particularly in communities with high rates of consanguineous marriages. For example, the incidence in Saudi Arabia is estimated at 1 in 2,500 live births (1) and in Slovakian gypsies it is 1 in 1,250 live births (2). In my home country of Egypt, the incidence is likely to parallel that of Saudi Arabia, as we have similar, close community structures. Although no formal data are available, my local hospital statistics reveal that almost two new cases present every month. This is in stark contrast to the Western community; in the UK, a general ophthalmologist can expect to see one new case every 5 years!Glaucoma presents in Western communities typically as a mild form, with predominantly large, usually clear, cornea; mild to moderate IOP elevation, and minimal optic nerve cupping. In contrast, the most common presentations in Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and South-East Asia are the more severe forms, with large, usually hazy, corneas (see Figure 1a) and severe IOP elevation with an optic nerve that is unable to be visualized on examination.

Diagnosis

Despite occurring relatively rarely, ophthalmologists and physicians need to be particularly vigilant for pediatric glaucoma. Untreated, it results in significant, lifelong morbidity from childhood onwards. This impacts immediate family, care providers and the community as a whole. Improperly managed, the disease has significant morbidity. Worldwide, childhood glaucoma accounts for approximately 18 percent of all children in institutes for the blind, and is responsible for about five percent of all childhood blindness (3). Ultimately, this ends up with significant losses in productivity and community resources, to an extent that rivals other eye diseases acquired in adulthood. To top it all, caring for a disabled child takes a heavy toll on the productivity of family members and/or care providers. On the other hand, proper and timely management results in significant improvement and reduction in morbidity (see “Who Makes a Full Recovery, and Who Doesn’t” ).Progressive cupping of the optic nerve (see Figure 1b), which is the hallmark of pediatric glaucoma, is associated with elevated intraocular pressure (IOP). This is difficult to quantify accurately in children, who do not want to have their eyes interfered with. Optic nerve cupping is ascertained by fundoscopy (mostly indirect) in cases of clear media, or sonographically in cases of opaque media. IOP can be measured by a multitude of methods, such as with slit-lamp-mounted Goldman applanation tonometers for (cooperative) older children. For less cooperative children, anesthesia may be required – with its well-established risks – but can potentially be avoided by using a hand-held applanation tonometer called the Tonopen (Fig. 1c) or a Schiotz (indentation) tonometer. Portable rebound tonometers are also useful for measuring IOP in children and do not require eye-drops to be used.

Even with these advances in tonometry, examination under anesthesia (EUA) plays an important role in the diagnosis of congenital and juvenile glaucoma. EUA lowers IOP, making it particularly difficult to quantify IOP accurately. The key to the diagnosis is therefore “change”; progression of the examined ocular parameters, especially optic nerve cupping, which happens early and quickly in children, is crucial to prove the diagnosis, particularly in cases where there is a reasonable level of doubt. Secondary changes in ocular biometric parameters include possible increases in the corneal diameter with broadening of the limbus and axial length (see Figure 1d).

Treatment

Most children have surgery to treat their glaucoma; medication is only used as a temporary measure when preparing for surgery, or if surgery fails to reduce IOP to acceptable levels. Many drugs are available to control adult glaucoma, but two key issues come into play when they are used in children. In practice, ?-agonists such as brimonidine or apraclonidine are best avoided, but if they are used at all, it must be with caution. Pediatric use risks central nervous system (CNS) penetration leading to CNS depression, which can result in reductions in heart and breathing rates, and potentially loss of consciousness, coma and even death. ?-blockers like timolol are no safer and need be used at the lowest possible dose to avoid potential systemic toxicity from nasal mucosal absorption. Children have a much lower body surface area than adults; for any given drug dosage, drug exposure is therefore far greater in children than in adults, hence the increased risks. This is particularly marked with drugs that have narrow therapeutic indices, such as ?-agonists and ?-blockers. “Safer” therapeutic choices in children include carbonic anhydrase inhibitors, such as dorzolamide or brinzolamide, or prostaglandin analogs (PGAs) like latanoprost or travoprost, with PGAs being especially effective for juvenile glaucoma, particularly the secondary forms.Who makes a full recovery, and who doesn’t?

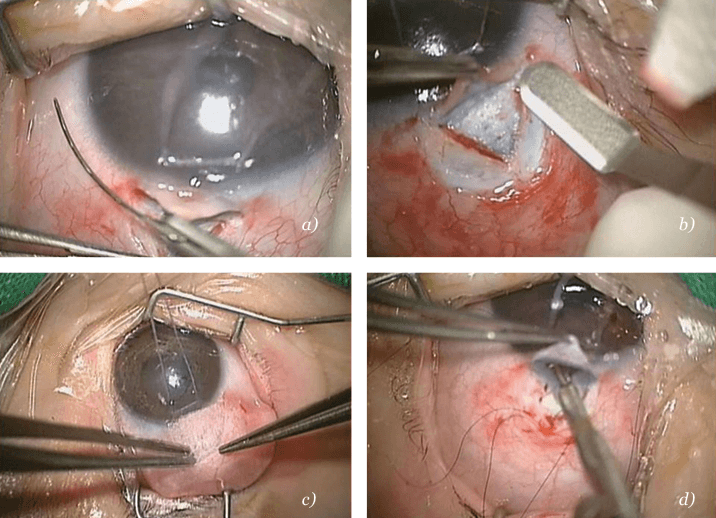

In the West: A population-based study in Olmsted County, Minnesota, USA (4) surveyed childhood glaucoma cases over a 40-year period. Twenty percent of untreated cases eventually resulted in enucleation of a blind painful eye. However, timely management resulted in over 85 percent of children having vision better then 20/200 after five years, with 77 percent retaining this level of acuity after 10 years. In the East: A study in Saudi Arabia supports the view that glaucoma presentations are more severe in Eastern communities. Timely management combined with surgery resulted in complete success in close to 75 percent of cases; less aggressive interventions had lower success rates (5). In my series, successful surgery has managed to cure 95.5 percent of children with PCG and 83 percent with glaucoma after congenital cataract surgery. Of these, corneal edema and scarring with subsequent partial morbidity accounted for 15 percent of PCG cases and seven percent of glaucoma after congenital cataract surgery cases. Permanent morbidity was present in the failed cases (4.5 percent and 17 percent respectively).Surgical choices in juvenile glaucoma are limited, with filtering surgery, also known as trabeculectomy (see Figure 2b, 2d), along with antimetabolites (see Figure 2c) being the clear procedure of choice. Choices for congenital and infantile glaucoma are more diverse. In cases with clear corneas and relatively mild IOP elevation (that is, a typical Western presentation), angle surgery – whether ab interno goniotomy or ab externo trabeculotomy (Fig. 2a) – is an effective and valid choice, and normally highly successful. For cases with hazy cornea and an accompanying severe elevation of IOP (that is, case presentations typical of Egypt and other Eastern locations), the only possible angle surgery is ab externo trabeculotomy. Other options include trabeculectomy with special emphasis on the use of antimetabolites, and primary glaucoma drainage devices, such as the Bærveldt implant or the Ahmed valve. In severe cases, a combination of procedures is especially useful, such as combined trabeculotomy-trabeculectomy and topical application of cytodestructive mitomycin C, for which reported success rates are in the range of 75 to 94 percent (4, 5).

In Egypt, multiple surgical procedures are commonly required to control IOP, particularly for the severe, “Eastern” case presentations. My personal reoperation rate is close to 20 percent (6). For apparently hopeless cases, cyclodestructive procedures remain a valid option, with transcleral cyclophotocoagulation being the procedure of choice. Endoscopic cyclophotocoagulation is an additional option that allows controlled selected destruction of ciliary processes and is considered to be safer.

Pediatric glaucoma has high morbidity, a lifelong impact, and causes significant economic burden. Timely diagnosis and intervention are crucial. Medical therapy is a temporizing measure, but only surgery provides a definitive treatment – and many surgical options are available. If diagnosed early enough, and properly managed, a child can have a near-normal lifestyle and be saved from a grim future of poor vision progressing to blindness.

Nader Bayoumi is Assistant Professor of Ophthalmology at Alexandria University Faculty of Medicine, Egypt.

References

- B. A. Bejjani et al., “CYP1B1mutations and incomplete penetrance in an inbred population segregating primary congenital glaucoma suggest frequent de novo events and a dominant modifier locus,” Hum. Mol. Genet., 9, 367-74 (2000). A .Gencik, “Epidemiology and genetics of primary congenital glaucoma in Slovakia. Description of a form of primary congenital glaucoma in gypsies with autosomal-recessive inheritance and complete penetrance,” Dev. Ophthalmol., 16, 76-115 (1989). C. E. Gilbert et al., “Causes of blindness and severe visual impairment in children in Chile,” Dev. Med. Child Neurol., 36, 326-33 (1994). P. B. Mullaney et al., “Combined trabeculotomy and trabeculectomy as an initial procedure in uncomplicated congenital glaucoma,” Arch. Ophthalmol., 117,457-60 (1999). A. K. Mandal, T. J. Naduvilath, A. Jayagandan, “Surgical results of combined trabeculotomy and trabeculectomy for developmental glaucoma,” Ophthalmology, 105, 974-82 (1998). N. Bayoumi, “Primary congenital glaucoma in the most populous Arab country, a single surgeon experience. Poster P304 at the 5th World Glaucoma Congress, Vancouver, Canada, July 17–20, 2013.