Children photo images sourced from: Pexels.com

Pediatric strabismus affects 0.14–5.65 percent of children, with an estimated average prevalence of 1.93 percent worldwide. In the US, it is classed as one of the most common medical eye disease diagnoses in early vision care. Though the condition is generally pediatric in nature – potentially leading to amblyopia, diplopia, loss of binocularity, and psychological effects for both the child and parents – adults also face increased risks of mental health conditions, including anxiety and depression.

While discussing the main challenges of strabismus in the child-patient population, Janine Collinge, pediatric ophthalmologist and Chair of Public Information Committee with the American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus (AAPOS) highlights a major issue: “difficulties with access to care and low/declining reimbursement for services,” especially in the pediatric arena. “There is a national shortage of pediatric ophthalmologists, and there are deserts of pediatric eye care across the country,” she says.

The UK is facing similar issues. “Not every place offers the same level of eye care for children” says Saurabh Jain, Consultant Ophthalmic Surgeon and Clinical Director of Services at the Royal Free London NHS Foundation Trust. “Some schools offer pediatric eye screening and some do not, even though it is one of the most cost-effective ways of picking up asymptomatic childhood eye disease,” he adds. Again, Jain also suggests that there is a nationwide shortage of pediatric ophthalmologists in the UK.

Public awareness of the condition is another important component, says Jain, pointing to “a lack of information about eye conditions that affect children and their correct treatment” – partly because of under-investment in pediatric eye care, but also because of the lack of exposure to ophthalmology in general and pediatric ophthalmology in particular in medical school training.

In the US, the financial element must also be considered. “A key factor influencing the number of pediatric ophthalmologists and the distribution of the pediatric ophthalmologists is reimbursement rates for this highly specialized eye care, particularly when it comes to Medicaid,” explains Collinge. “With the rising costs of running a practice, many physicians are forced to restrict their practice to patients with more favorable payer rates and limit the numbers of patients with low paying insurance (like Medicaid) in order to be able to afford to keep their doors open. Ophthalmologists in training are aware of the reimbursement challenges, and some of them are choosing not to go into pediatric ophthalmology [precisely] because of this.”

Ophthalmologistsis also face the issue of adequately communicating what strabismus involves and what subsequent treatment of the condition will look like. “Some of the big challenges in patient and family education, in terms of eye care, are reliant on time and appropriate resources,” Collinge notes. Indeed, with challenges in pediatric eye care accessibility and reimbursement, many ophthalmologists do not have enough time in their day to educate both patients and families. Collinge continues: “In addition to the stresses of life and increased cost of living, parents and caregivers may not have enough time or energy themselves to truly engage with thoughtful discussions about their child’s eye care.”

Does technology have an answer here? “With the advent of AI and new imaging modalities, we have access to more data and information than we ever had before,” says Jain. “However, communicating this to children and families in as clear a manner as possible remains complicated,” especially when parental expectations do not coincide with what treatment plans can deliver.

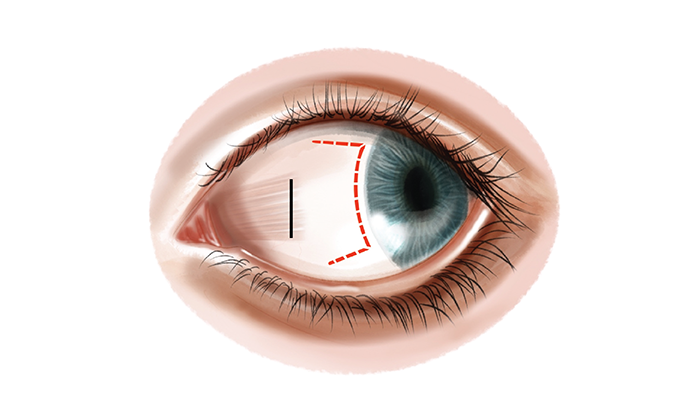

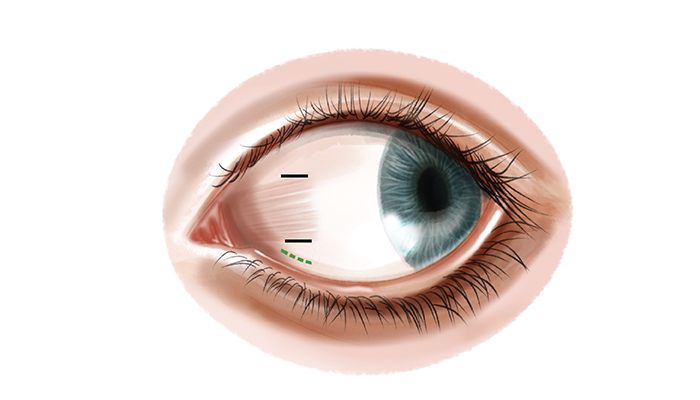

In terms of therapeutic advancements, though strabismus treatments have remain relatively unchanged over the years, the industry has seen some surgical progress in recent times. Jain explains how researchers have begun to understand the fact that “the muscles are innervated in such a way that they work within compartments, so this can be utilized to improve the surgical outcomes by selectively weakening or strengthening the muscle fibers.” He points to a new focus on minimizing the size of the incision used for surgery – both to improve patient outcomes and reduce inflammation. “Minimally invasive strabismus surgery is rapidly becoming the new standard of care,” he says. Figure 1 (in red) shows the standard incision; minimally invasive incisions are shown in green and black in Figure 2.

In addition, Collinge emphasizes the current trend towards understanding the root cause of strabismus – at the genetic level. “It is hoped that this type of research, presented at this year’s annual AAPOS meeting will lead to better answers and better counseling for patients and parents, as well as potentially better treatments,” she says.

Ultimately, the research and treatment landscape for strabismus does appear to be changing for the better, with surgery incidences in childhood strabismus witnessing a decline – especially in the UK and US. Although the reasons for this remain somewhat opaque, Saurabh Jain believes that the drop could possibly be attributed “to the general improvement in social economic status and nutrition,” as well as “a better understanding of how to manage strabismus in children by non-surgical means, and earlier presentation of children with these problems to an eye clinic.”

However, Collinge is less optimistic, especially given the issues with access to healthcare in the US. “There is concern that increasingly more children may have to suffer with untreated eye disease for long periods in their life,” she notes. “This has the potential to impact vision, learning, and development. It could furthermore impact productivity in adulthood. Only time will tell.”

Figure 1

Figure 2