- SMILE is a surgical technique, principally for the treatment of myopia, that uses only a femtosecond laser and does not require the creation of a flap

- Benefits include faster treatment times, fewer side effects and avoidance of tissue ablation, which carries corneal biomechanical advantages

- Disadvantages include the cost of the laser and accessories – Zeiss is the only manufacturer – and the fact that SMILE (currently) provides no improvements in refractive outcomes over traditional LASIK

- Further refinements and improvements to the technique are possible and will allow it to achieve its true potential - as the surgical procedure of choice for a wide range of refractive disorders

Small incision lenticule extraction (SMILE) is a fairly recently developed form of refractive surgery that’s performed almost entirely with a femtosecond. I would like to tell you about my own experiences with SMILE and my thoughts about its place in the future of laser eye surgery. But first, I‘d like to briefly explain how it works. The femtosecond laser is used to cut a refractive lenticule into the cornea and create a small incision, through which the lenticule is manually extracted, eliminating both the need for an excimer laser and the creation of a flap. An all-in-one procedure like this offers a number of advantages over traditional LASIK; for instance, using only one laser means that there is no need to move the patient during surgery, while the absence of a flap reduces biomechanical impact by leaving the anterior corneal surface undisturbed. Most significantly, SMILE involves the manual removal of the lenticule from the corneal bed, which – when you compare it to the tissue ablation method employed by the excimer laser – allows us to reduce damage to tissue, and avoid photoablation-related side effects. Despite these benefits, the procedure has not yet become established as a standard surgical treatment – the cost of the necessary equipment is high, and so far SMILE offers no better refractive outcomes than traditional methods.

I began performing SMILE three and a half years ago, after I went to India and met Rupal Shah – one of the only people performing SMILE at the time – and I thought that the procedure looked very promising. We introduced it into our own clinic by doing only a few of these femtosecond laser-only procedures at first, but after about a year, we decided that they were both safe and promising – so SMILE became our standard procedure. Today, I am the head of a team that includes four optometrists and three corneal surgeons. The optometrists are responsible for all of our preoperative evaluation, while the surgeons carry out the actual procedures.

SMILE step-by-step

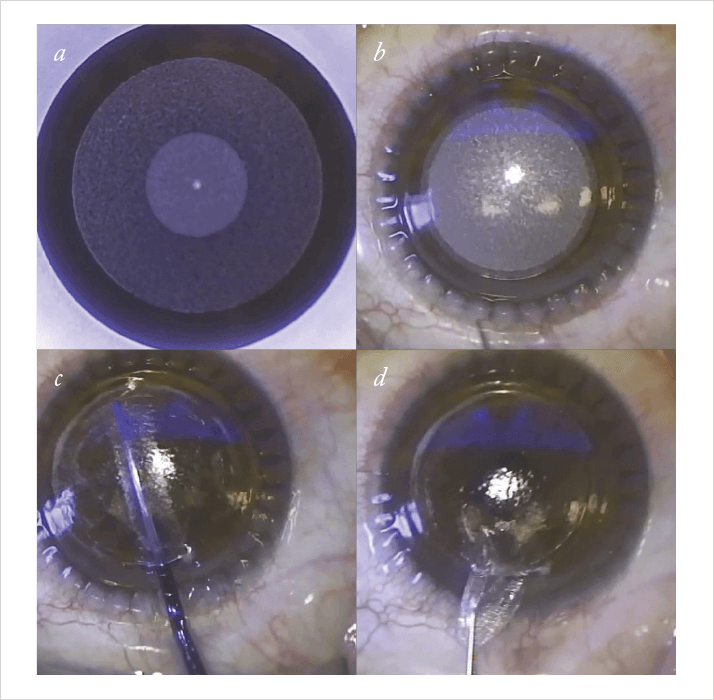

I will walk you through my standard approach to SMILE, which I believe is simple to perform and I find achieves consistent results. Before beginning the procedure, we prepare the patient for surgery, first by administering two drops of topical anesthesia and then by explaining the procedure to them – including the lenticule incisions, its removal, and the post-surgical eyedrop regimen – and reassuring them that it will be painless. The patient is instructed to fixate a blinking target light, and to remain calm during the operation of the laser.To start the procedure, we place the patient on the laser bed and patch the left eye, as we always start with the right. After putting in an eyelid speculum and cleaning the right eye with saline and a sponge to remove any debris from tears, we position the patient under the operating microscope and the laser and make sure that they can see the fixation light. As we apply suction, we ask the patient to relax for the next 30 seconds so that we can run the laser (Figure 1a, b). This usually goes smoothly, and once we are finished, we can release the suction pressure and move the patient to the observation position on the bed while keeping them under the microscope. Using a thin spatula, I perform the first dissection above the lenticule to be removed, perform the second dissection below the lenticule (Figure 1c), and then remove it (Figure 1d). Finally, I put some antibiotic drops and diclofenac into the eye, before repeating the entire procedure again on the left eye.

Once both extractions are done, the patient can sit up and relax; often, they go out and wait for about 20 minutes while we perform the next operation. Then we take a look on a slit lamp, just to see if there is any debris or fibrillar material on the surface – which, usually, there isn’t. At that point, the patient can leave; we send them home with antibiotics and weak steroids to use four times a day. We see the patient again the day after surgery, check on corrective visual acuity, and explain what to watch for during the recovery period. Our patients are usually seen by their local ophthalmologists after one week and then come back to us after three months so that we can do a sort of “quality check” – see if the patient is happy and what refraction they’ve ended up with.

Ensuring only eligible candidates undergo the laser refractive surgery is always of the utmost importance. Currently, we use the same inclusion criteria for SMILE as for LASIK surgery: patients need to have a residual stromal bed of at least 250 µm, and we also perform a thorough preoperative investigation to exclude patients with subclinical keratoconus. I think that, in a few years, we may be able to loosen the criteria a little, because the anterior corneal surface is more or less undisturbed by this procedure, which I would assume makes the cornea biomechanically stronger. For the moment, though, we use the same criteria for both surgeries.

Is the future of SMILE… the future of laser surgery?

Some people have said that, while SMILE is definitely the future of laser eye surgery, the lasers aren’t quite good enough yet. The technique itself appears to be what we’ve been waiting for since the late 1990s, when the first femtosecond lasers were developed – but there are still problems related to using femtosecond lasers. One prominent example is that you have to make two cuts, and you need to start with the deep cut – if you have any small bubbles that combine to form larger ones, you can run the risk that your second cut could be affected by these bubbles. But using the standard spot distance and energy settings on the VisuMax laser (Carl Zeiss Meditec, Jena, Germany) we rarely have any problems with big bubble formation in the lower cut – although the actual dissection of the lenticule can sometimes be a little difficult. You occasionally have to use a little more force than you would like to, so I hope that this will be addressed in future versions of the technology. In terms of further optimizing the quality of the lenticule cut, I hope that a standardized, smooth and easy dissection will be simpler to achieve than it is now. It isn’t common for pieces of the lenticule – for instance, a little of the periphery – to be left in the interface; that happens only rarely even now. But I have reason to believe that the actual cut quality, though already good, will be made even smoother in the future by developments in femtosecond laser technology – and I think many other laser companies will be attempting to do this with any number of new lasers and approaches.But I think that, at least when you get as experienced with the SMILE technique as we are today, it is as safe as the LASIK technique. We have found that recovery might be a little slower, but the end result is as safe as LASIK surgery. And when you treat high myopia with SMILE as opposed to with LASIK, in our experience the SMILE surgery can more precisely achieve the spherical equivalence that we want.

Cost and Competition

SMILE has the potential to be faster than other laser refractive techniques; there is no need to move the patient from a femtosecond laser to an excimer laser as there is in LASIK. And when you have experience with the technique, you can do two eyes in 20 minutes, which is pretty fast. There is a higher cost associated with it in comparison with LASIK, but I think that is something that every institution negotiates individually. So let’s break down the financial investment that you would need to incorporate the technology. The actual list price of the VisuMax laser is about €500,000, and then you need to buy a separate software module specifically for SMILE surgery. You also need a single-use suction device for each patient, which is an additional cost – and I think the company charges a little more for the device if you want to use it for a SMILE procedure as opposed to a LASIK procedure. So I do think the company tries to market SMILE as a sort of high-end procedure, and I think people are beginning to see it as the premium procedure of corneal laser refractive surgery.One of the problems with cost is that Carl Zeiss Meditec is currently the only company manufacturing a laser capable of creating a refractive intrastromal corneal lenticule; more companies need to develop similar products so that use of the SMILE technique can be expanded - and competition might bring prices down! I think this could depend on Zeiss licensing the patents, and also on other companies’ ability to manufacture and sell lasers suitable for SMILE.

It’s possible that in 10 years’ time, almost everyone will undergo SMILE procedures, rather than LASIK. But for applications like treating very low myopia, traditional photorefractive keratectomy (PRK) has also been extremely successful. Large studies have been published that show that good results can be expected with this type of surgery as well. SMILE is also not used as a retreatment procedure. At the moment, surgeons either open the SMILE cap with a femtosecond cut that resembles a LASIK flap and then use an excimer laser for the retreatment, or they use our preferred method, which employs an excimer laser to perform a transepithelial PRK on a cornea that has undergone SMILE. So there is still a need for excimer laser procedures as we continue to optimize the SMILE technique.

Improving and expanding SMILE

I think the future of SMILE lies in optimizing the femtosecond laser to perfect the actual lenticule cutting – whether this is done by smaller bubble creation, faster shooting of the laser, or something else. There are various options, and it is hard to say exactly how far in the future these developments will be or to what extent they will actually improve the results of the procedure, but I’m optimistic. Also, the SMILE procedure right now is really only for myopia and myopic astigmatism. I think that there’s a need for the procedure to be developed into a hyperopia treatment, which involves software that hasn’t been released yet. It’s relatively easy to program the laser to treat hyperopia, but there can be technical issues related to cutting the donut-shaped lenticule that is needed to treat the condition. Again, that has something to do with how the bubbles form and how well the periphery of the lenticule is cut.There are still challenges to be addressed before SMILE can become a standard treatment in the clinic. The cost of purchasing a femtosecond laser, software and accessories is very high at the moment, and because the refractive results show no clear-cut advantages over traditional methods, surgeons may be hesitant to adopt an expensive new technique like SMILE. I do think that it has promise though, especially as it offers a reduced risk of side effects from tissue ablation or flap creation. In my opinion, SMILE is the future of refractive surgery, and I think we can expect to see more and more interest in it in the future.

Jesper Hjortdal is Clinical Professor in the Department of Ophthalmology at Aarhus University, Aarhus, Denmark.