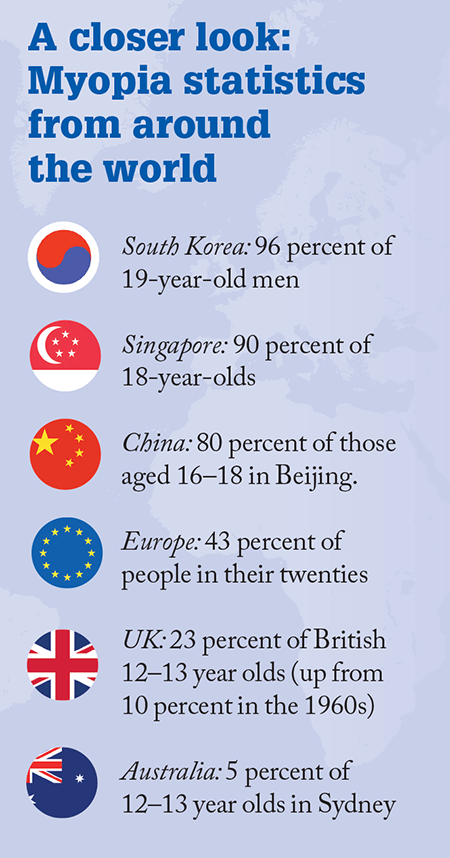

Children are increasingly becoming myopic – and the fact that the proportion of British children aged 12 or 13 with myopia has risen from 10 percent in the 1960s to 23 percent today was recent front page news in the UK-based newspaper, The Times (1). The onset of myopia typically starts when children are aged 6 or 7 years old, and a number of factors have been identified that might be causing this rise in myopia: close work, socioeconomic factors, and time spent outside as a child, with the latter gaining a lot of traction recently (2).

- Accommodative convergence to accommodation ratio

- Axial length

- Crystalline lens power

- No. of myopic parents

- Corneal power

- Visual activity

- Astigmatism magnitude by orientation (Horizontal/vertical and oblique)

- Accommodative lag

- Crystalline lens thickness

- Refractive error

- Relative peripheral

- Spherical equivalent at baseline

- Time spent outdoors

Myopia can be more than just a mild inconvenience – high myopia is a major cause of legal blindness, as it increases the risk of premature cataracts, glaucoma, retinal detachment and macular degeneration. Interventions – like potentially increasing time spent outdoors – that could reduce the incidence, or mitigate the rate of development of myopia, would therefore be worthwhile. So what if you could predict which six-year-olds would become myopic by the age of 13? One study – The Collaborative Longitudinal Evaluation of Ethnicity and Refractive Error (CLEERE) – followed more than 4,500 (initially) non-myopic children in the US, between the ages of 6 and 13 years (3). Five clinical centers were involved in CLEERE, which ran between September 1989 and May 2010, and the study investigators evaluated 13 candidate risk factors (Table 1) for their ability to predict the onset of myopia (defined as −0.75 diopters or more of myopia in each principal meridian in the right eye at any visit until the age of 13 years).

What did they find? Of the 13 parameters evaluated, 10 were associated with a significant risk (p<0.05) of myopia onset, and after multivariate modelling, eight retained this association. However, spherical equivalent refractive error was the single best predictive factor – and one that performed as well as all eight factors combined. There were some surprises, too. “Near work has been thought to be a cause of myopia, or at least a risk factor, for more than 100 years. Some of the studies that led to that conclusion are hard to refute. In this large data set from an ethnically representative sample of children, we found no association,” says lead researcher Karla Zadnik. Notably, neither time spent outdoors nor having myopic parents was found to have any association with the development of myopia. The researchers believe this work has two key implications. First, this knowledge can be used to monitor school-aged children who may have future vision problems, and second, it might enable the identification of candidates for enrolment into clinical trials of therapies designed to prevent myopia. “As people become aware of a test for their first-grader that would help predict whether their child will need glasses for nearsightedness, I think myopic parents who want to have this information about their kids could lead to rapid adoption of this test,” says Zadnik.

References

- C. Smyth, “Huge rise in short-sighted children blamed on indoor lifestyles”, The Times (April 25, 2015), available at: http://bit.ly/timesmyopia. Accessed May 01, 2015. L O’Donoghue, et al., “Risk factors for childhood myopia: findings from the NICER study”, Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci, 56, 1524–1530 (2015). PMID: 25655799. K Zadnik, et al., “Prediction of juvenile-onset myopia”, JAMA Ophthalmol, [Epub ahead of print] (2015). PMID: 25837970.