Myopia is increasingly prevalent worldwide (1), but the mechanisms by which it develops are still unknown. Researchers from Northwestern University, Chicago, might have uncovered a clue: a new type of retinal ganglion cell (RGC) in mice, dubbed an ON delayed RGC. Highly sensitive to light and image focus, they hypothesize that the newly discovered cell could be involved in the control of emmetropization. Gregory Schwartz, who led the associated study (2), talks about the work behind the theory.

What inspired your study?

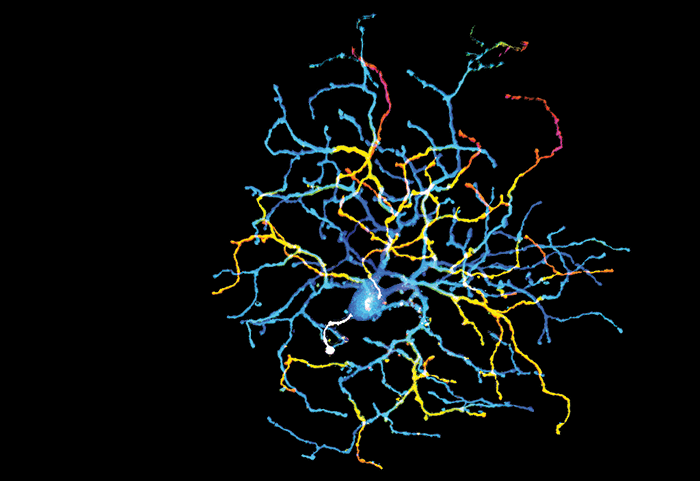

My lab measures the light responses, morphology, and genetic signature of individual RGCs. This study was part of a large effort to characterize all the RGC types in the mouse – of which there are around 50 – and several lines of evidence suggest we are nearing completion in our effort.What did you find?

We found an RGC with a very unusual receptive field, which we named “ON delayed RGC,” because it has a very long response delay. Studying the circuit mechanisms responsible for this delay and the cell’s other unique receptive field properties revealed several new functional roles of inhibition in the retina. We also found that the ON delayed RGCs are more sensitive to the global focus of an image than any other RGC we measured – this observation led us to speculate about its role in myopia.What were the surprises along the way?

This project has been full of surprises! Perhaps the biggest one was the apparent paradox that a cell with an unusually large receptive field and no surround suppression was actually the most sensitive RGC to the fine spatial scales that change with image focus. Several elements of this RGC’s circuit mechanisms were also surprising, including its activation well beyond its dendrites. The dendritic field of a RGC has always been viewed as a good approximation of the size of its receptive field; that relationship is broken in ON delayed RGCs.And the challenges?

The source of activation beyond the cell’s dendrites stumped us for a while. Carefully measuring the voltage-dependence of the current responsible for this activation revealed it was disinhibitory and carried by K+ – a very unusual kind of synaptic current to find in a RGC. Also, we went through many ideas about the functional role of ON delayed RGCs before landing on the hypothesis about a global focus signal involved in emmetropization and accommodation.What impact could your findings have?

The connection with emmetropization is currently speculative but, if proven, it opens a completely new target for clinical interventions in the prevention of childhood myopia. Knowing the cellular substrate of the global focus signal would be a landmark that has eluded the field for decades. The unique disinhibitory current may even offer a clue into a specific pharmacological target to manipulate ON delayed RGCs in vivo. This current relies on GABAB receptors, which have minimal roles in other retinal circuits.What are your next steps?

We are pursuing two main lines of research. The first is using retrograde viral tracing to see if ON delayed RGCs project to areas in the brain known to control pupil dilation to establish a role in accommodation via the pupillary near reflex. The second is using single cell RNA-sequencing to identify genes specific to ON delayed RGCs. With such genes, we will be able to use modern genetic tools to manipulate this cell during development and measure possible changes in eye growth.References

- BA Holden et al., “Global prevalence of myopia and high myopia and temporal trends from 2000 through 2050”, Ophthalmol, 123, 1036–1042 (2016). PMID: 26875007. A Mani and GW Schwartz, “Circuit mechanisms of a retinal ganglion cell with stimulus-dependent response latency and activation beyond its dendrites”, Curr Biol, (2017). [Epub ahead of print]. PMID: 28132812.