- Although endophthalmitis is an uncommon complication of cataract surgery, its prevention is paramount

- Convenience, cost and physical ability all decrease patient compliance with antibiotic drop regimen

- Transzonular placement of antibiotics and steroids improves penetration and eliminates compliance issues

- Advances in compounded formulations means that a single injection could suffice for most – and avoid eyedrops

Cataract surgery is one of the safest procedures in all of medicine and has exceptionally high satisfaction rates. However, post-cataract surgery infection rates have been rising since 1994 (1), and the potentially serious consequences of endophthalmitis make its prevention of great importance. While discussions continue over the role of clear corneal incisions and other factors (2), most cases of sporadic postoperative infection are known to be a result of the patient’s own periocular flora (3), and increased infection risk from wound leakage. (4)

The drawbacks of topical medications

The most common prophylactic strategy against endophthalmitis is the use of topical antibiotics. They can be applied before surgery to reduce the number of microbes on the ocular surface, during surgery to reduce the microbes reaching the intraocular environment, and after surgery to eliminate any that may have reached the eye. While physicians can apply povidone iodine to the surgical area and add antibiotics to the irrigating solution during the perioperative period, the efficacy of protection is still largely dependent on patient compliance with a postoperative antibiotic eye drop regimen. There are two obvious drawbacks to this approach. First, patient compliance is dismal. It relies on patients purchasing their drops, which in some locations can be very costly, and remembering to instill them properly. Even if they have the drops and intend to use them, they still may not be complying correctly with their doctor’s instructions. In fact, one study found that over 92 percent of cataract patients administer their eyedrops incorrectly (5).Some of the common reasons for this include: patient administration of multiple eyedrops in quick succession and leading to their dilution (therefore reducing effectiveness); patients forgetting which drop they’ve already taken (and making their own decisions on how to compensate for this); patient failure to dose at regular intervals. And if a patient is already on glaucoma drops, this can only add to the confusion. The second major drawback to topical antibiotic drops is that endophthalmitis results from an infection that takes hold in the vitreous. However, drops treat the ocular surface, which means that drug penetration and concentration within the vitreous varies.

A dropless alternative

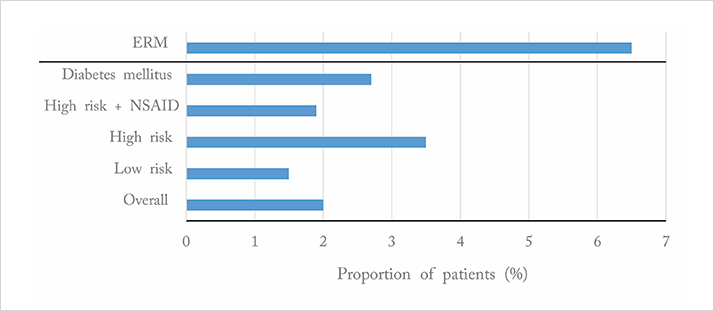

Convincing evidence shows that antibiotics injected into the eye are not only just as safe as topical antibiotics, but they’re more clinically- and cost-effective (6). Importantly, numerous studies have found that the rate of endophthalmitis is reduced to 0 percent when a prophylactic antibiotic is injected intracamerally at the end of a procedure (7,8). Now the prospect of dropless cataract surgery has leapt closer to reality. Compounds have been developed that can be administered in single dose injections (transzonularly), and combine both the antibiotic and steroid necessary following cataract surgery. Tri-Moxi (triamcinolone acetonide and moxifloxacin hydrochloride) and Tri-Moxi+Vanc (with vancomycin) (Imprimis Pharmaceuticals, San Diego, CA, USA) are patent-pending, proprietary formulas that have optimized solubility and viscosity for ocular injection through small needles and cannulas (27- or 30-gauge) during cataract surgery. The compounds have been formulated to be better retained in the vitreous than in the anterior chamber and so can be released gradually without risking toxicity to the corneal endothelium or altering the outflow of the trabecular meshwork.Putting the findings of others to the test, Stewart administered Tri-Moxi, instead of topical medications, in 1,575 eyes of patients who underwent cataract surgery (9). All of his patients were seen post-operatively on the same day, and three to four weeks and six months post-op. Not one of his patients developed endophthalmitis and 98 percent remained free from cystoid macular edema and inflammation (Figure 1).

Addressing steroid and injection concerns Intuitively, you might worry about potential injection-related problems, like breaking zonules or having the vitreous run into the anterior chamber. This has not been a concern based on our experience though – today it just feels like a standard part of the cataract procedure. Patients with small pupils can be a little more difficult because you cannot guide the cannula as you normally would. If you do bump a ciliary process and cause it to bleed, it is not the end of the world, you just raise the pressure in the eye for a few minutes to stop the bleeding – much as you would put pressure on any wound.

Some surgeons use Tri-Moxi on the majority of patients, but hesitate to perform the injection on patients with glaucoma. We feel that there is no reason to exclude this patient group – retina specialists have been injecting triamcinolone into the posterior chamber for a long time, and have found it to be completely safe below a 4 mg threshold. Tri-Moxi was developed at 15 mg/5 ml; most users inject 0.2 ml, delivering a 0.3 mg of triamcinolone dose into the eye – well below that 4 mg threshold that might trigger a steroid response. There has been talk about increasing the amount slightly to reduce the cases with rebound inflammation, but it has not been done specifically to avoid any risk of steroid response. Currently, our rate of rebound inflammation lies at just 2.5 percent.

No need to panic

Although patients are overwhelmingly happy to get rid of the three to six weeks of drops, adequate patient education is a necessity. When we first started performing dropless cataract surgery, our patients went on to experience floaters or cloudy vision (a natural occurrence given that an opaque liquid is injected into the eye) and were calling us in a panic. We realized that we needed to improve our patient education preoperatively and we needed to make sure that the post-operative nurse reminded them that they may experience these things – and that it’s temporary. We have found that when patients weigh the benefits of dropless surgery with the downside of the floaters, they universally prefer to receive the injection. You need to explain to your patients that their vision will be very poor on the day of surgery, but by the next morning, most of that will have lifted – the ‘wow’ effect of cataract surgery is not lost with these patients.

As great as the benefits of dropless cataract surgery are in “regular” patients, they’re even greater in patients with certain disabilities. As Bradford, UK-based ophthalmologist Rachel Piling previously discussed in The Ophthalmologist, people with learning disabilities are 10 times more likely to have serious sight problems than the general population (10) – and this is a group that is also highly likely to need assistance with administering their eye drops. Everything from poor motor control to extreme phobia of eye drops can make compliance with a dosing regimen extremely difficult for these patients. Dropless cataract surgery has the potential to remove that worry from the ophthalmologist, the patient, and their carers.

On a mission

Understandably, compliance with eye drops is also of particular concern when providing foreign aid to underprivileged communities. Stewart makes annual trips to southern Mexico with World Cataract Foundation, and Cathy started the Southern Eye Clinic in Serabu, Sierra Leone in 2006. As with many other missions, patients may walk for days to reach a clinic to undergo cataract surgery, and then the surgeons have no contact with them again after they leave. It probably comes as no surprise to learn that there are many instances when treatment regimens are not properly followed in these regions. One example Cathy saw was a cataract surgical center that was set up in Sierra Leone several years ago – the conditions weren’t sufficiently sterile, and this resulted in about 200 people being blinded from endophthalmitis. In Serabu, Cathy had a patient that had cataract surgery; after going home, she returned weeks later with advanced endophthalmitis. Cathy tried to wash out the anterior chamber, and do an anterior vitrectomy, but the tools to treat that kind of disease just aren’t available out there. Knowing that all of your patients on such missions can go home after surgery having received all of their antibiotics and steroids should be a great comfort to any cataract surgeon.Cathy and Stewart both feel that transzonular injections of steroids and antibiotics should be considered as standard for those cataract patients with physical or learning disabilities, or in deprived geographical regions. With patient compliance being a global concern, however, they expect the number of surgeons replacing topical drops with injections will grow exponentially in the months and the years to come.

Cathy Schanzer is the Medical Director and Chief Surgeon at Southern Eye Associates in Memphis, TN, USA. M. Stewart Galloway is Medical Director at Cumberland Eye Care and Cookeville Eye Specialists in TN, USA.

References

- 1. M. Taban, A. Behrens, R. L. Newcomb, et al., “Acute endophthalmitis following cataract surgery: a systematic review of the literature”, Arch. Ophthalmol., 123, 613–620, (2005).2. M. Lundstrom G. Wejde, U. Stenevi, et al., “Endophthalmitis after cataract surgery: a nationwide prospective study evaluating incidence in relation to incision type and location”, Ophthalmology, 114, 866–870, (2007).3. M. G. Speaker, F.A. Milch, M.K. Shah, et al., “Role of external bacterial flora in the pathogenesis of acute postoperative endophthalmitis”, Ophthalmology, 98, 639–49, (1991).4. T. Wallin, J. Parker, Y. Jin, et al., “Cohort study of 27 cases of endophthalmitis at a single institution”, J. Cataract Refract. Surg., 31, 735–741, (2005).5. J. A. An, O. Kasner, D. A. Sarnek, et al., “Evaluation of eyedrop administration by inexperienced patients after cataract surgery”, J. Cataract Refract. Surg., online ahead of print. doi:10.1016/j.jcrs.2014.02.037.6. S. Ndegwa, K. Cimon, M. Severn, “Intracameral antibiotics for the prevention of endophthalmitis post-cataract surgery: review of clinical and cost-effectiveness and guidelines”, Ottawa: Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health, http://bit.ly/1omx44L. Accessed September 15, 2014.7. L. B. Arbisser, “Safety of intracameral moxifloxacin for prophylaxis of endophthalmitis after cataract surgery”, J. Cataract Refract. Surg., 34, 1114–1120, (2008). doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2008.03.017.8. V. Galvis, A. Tello, M. A. Sanchez, et al., “Cohort study of intracameral moxifloxacin in postoperative endophthalmitis prophylaxis”, Ophthalmol. Eye Dis., 6, 104, (2014). doi:10.4137/OED.S13102.9. M. S. Galloway, “Intravitreal placement of antibiotic/steroid as a substitute for post-operative drops following cataract surgery,” presentation at the American Society for Cataract and Refractive Surgeons Annual Meeting, Boston, MA, USA, April 25–29, 2014.10. R. Pilling, “Serving Patients who have Learning Disabilities,” The Ophthalmologist, http://bit.ly/1wrcSzJ. Accessed September 16, 2014.