Credit: Pxfuel.com

Credit: Pxfuel.com

According to the Tear Film and Ocular Surface Society Dry Eyes Workshop II (TFOS DEWS II), the global prevalence of DED is 5–50 percent, with a higher predisposition in women and elderly individuals (1). Patients with DED can experience several symptoms, including ocular irritation, itching, redness, mucous discharge, foreign body sensation, photosensitivity, and visual blurring (2, 3), which can affect common daily activities and exert a substantial economic burden on patients and society (4, 5).

To delay DED progression, early intervention and management is recommended (6). DED management aims to minimize evaporative tear loss, stabilize the tear film, protect the ocular surface, repair ocular surface damage, increase lubrication, enhance glandular secretion, and curb inflammation. The TFOS DEWS II report recommends step-wise management and considers artificial tears as a mainstay of DED therapy (7).

First-line fakes – artificial tears

Artificial tears are generally considered the first-line treatment for DED (3, 8). Artificial tear supplements are buffered solutions that contain electrolytes, surfactants, one or more viscosity agents or lubricants, and may or may not contain preservatives (7). Artificial tears typically target one or more layers of the tear film and have shown to improve visual acuity, contrast sensitivity, corneal epithelial regularity, tear film stability, and reduce ocular surface stress (9, 10, 11). Artificial tears also minimize desiccation and cell death by providing moisture and lubrication to the ocular surface (7, 12). Reported side effects of some artificial tear products include blurred vision, foreign body sensation, and ocular discomfort (7, 13).

Preservatives used in artificial tear products protect the product from microbial growth during normal conditions of storage and repeated withdrawal of individual doses. Moreover, preservatives allow a margin of safety if the product is inadvertently contaminated.

Chronic exposure to preservatives has been associated with side effects, predominantly toxicity and adverse changes to the ocular surface, resulting in disease progression, conjunctival scarring, exacerbation of ocular inflammation, decrease in tear break-up time, ocular tissue irritation and destabilization of tear film, burning and stinging sensations, foreign body sensation, and deterioration of vision (7, 14, 15, 16, 17). To avoid side effects associated with long-term exposure, newer gentler preservative variants, such as sodium chlorite (Purite, OcuPure), sodium perborate (GenAqua), polyquaternium-1 (Polyquad) have shown lower consequences on the ocular surface (7). However, studies have reported negative effects on the ocular surface following the use of sodium chlorite and sodium perborate (18). And so we look towards preservative-free (PF) eye drops as an important alternative.

The pros of preservative-free formulations

Preservative-free formulations are necessary for patients with severe dry eye, ocular surface disease, and impaired lacrimal gland secretion or for patients on multiple preserved topical medications for chronic eye disease (7, 19). But other patient specific factors can make PF formulations a better alternative (3, 7, 15, 19, 20, 21, 22):

History of allergy to preservatives

Contact lens wearers

High frequency of eye drop instillation

Longer duration of treatment

Exposure to desiccated environment

Women and elderly individuals

Asian ethnicity

Exposure to electronic displays for both work and leisure.

Severe dry eyes

Receiving multiple preserved drugs

Preservative-free eye drops cause the least disruption to the ocular surface at both clinical and cellular levels (23, 24). Additionally, PF formulations significantly improve tear ferning patterns, symptoms, and signs of DED after cataract surgery and may result in better adherence and persistence compared to preserved formulations (25, 26).

Previously published studies on switching to PF drops have shown ameliorated DED symptoms as well as improved clinical signs. In a large switch study including the majority of patients (81 percent) with severe DED and habitual users of preserved artificial tears, a minimum of three-weeks switching to PF eye drops reduced Ocular Surface Disease Index (OSDI) scores in 97 percent of the patients and reduced the prevalence of superficial punctate keratitis (27). Another case-controlled study reported significant improvements in symptoms, tear film break-up time, and Schirmer I scores in patients with severe DED when compared with preservative-containing eye drops (28). Moreover, tears from the PF group showed a significant decrease in inflammatory markers and significant increase in antioxidant activity compared with the group taking preserved eye drops.

Epidemiologic surveys carried out in patients with glaucoma reported that PF eye drops were less associated with ocular symptoms and signs of irritation than preserved eye drops (29). Another switch study reported an increase in tear film thickness, breakup time, and an improvement of Dry Eye–Related Quality-of-Life Score in patients with glaucoma or ocular hypertension who were taking preservative-containing eye drops for at least six months (20).

Commercially available PF eye drops include Systane (Alcon), Refresh (Allergan), Soothe (Bausch and Lomb), and Hylo-fresh (Scope Ophthalmics) – and their safety and efficacy is explained in detail elsewhere (23).

Unit-dose versus multi-dose

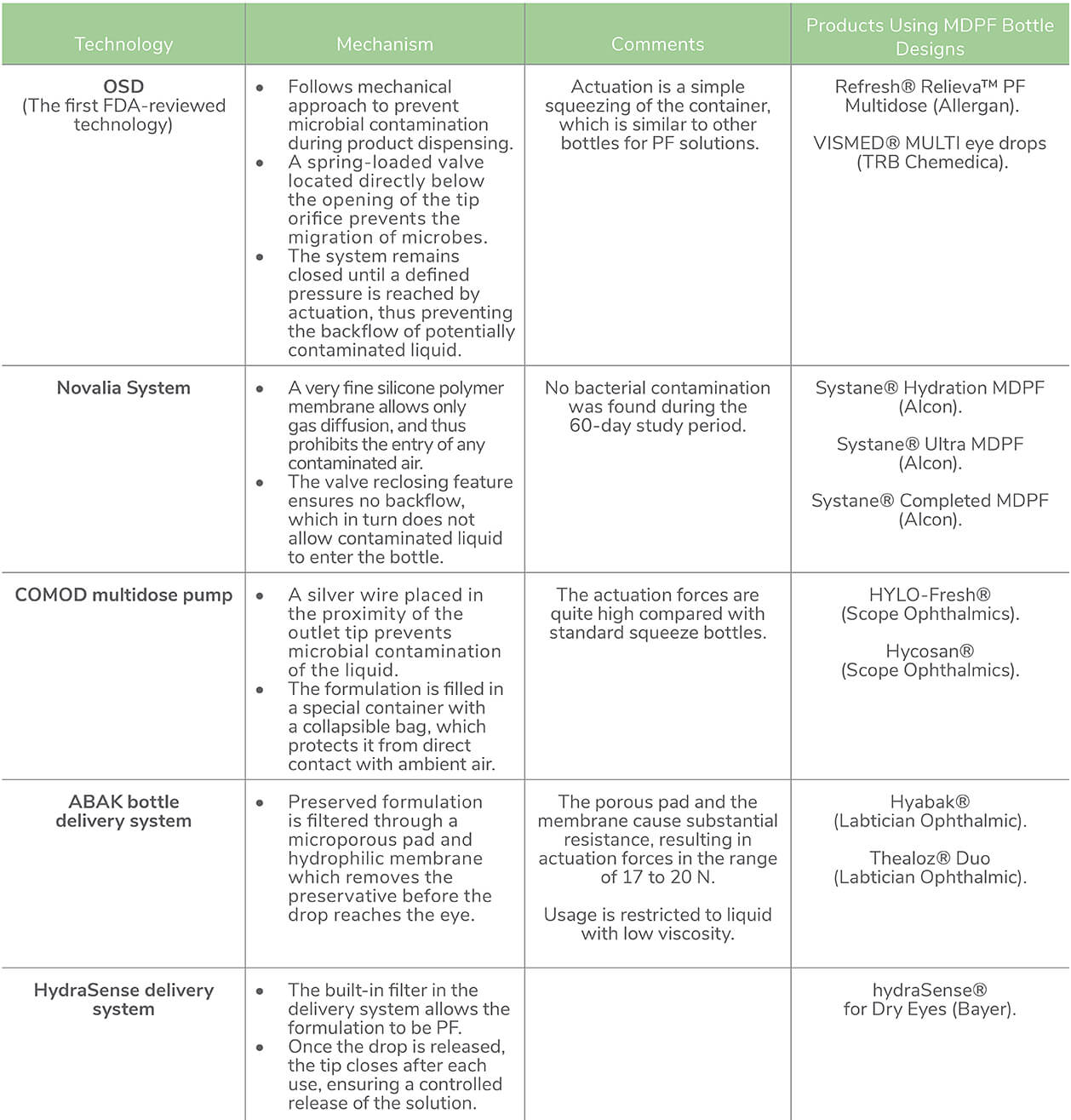

To deliver sterile drops without preservatives, packaging changes are necessary; PF preparations are typically supplied in a unit dose format (30). However, unit dose vials are not an ideal solution – less dexterous individuals (for example, elderly patients) may have difficulty opening the rigid plastic (17), inappropriate handling (or inadequate closure) can lead to contamination (31), the additional packaging makes them bulky to store, less convenient to carry, and also generates more plastic waste (32) – and all of these issues are exacerbated by the chronic nature of the condition and the high frequency of instillation. Multi-dose PF (MDPFs) could help with both functionality, storage, and transport, while ensuring a sterile formulation for long-term treatment (32). So far, a number of different technologies have been used in MPDF systems (see Table 1).

Table 1. Technologies used in multi-dose PF (MDPF) dispensation in lubricant eye drops. Abbreviations: FDA, Food and Drug Administration; OSD, ophthalmic squeeze dispenser; PF, preservative-free (33–39)

Table 1. Technologies used in multi-dose PF (MDPF) dispensation in lubricant eye drops. Abbreviations: FDA, Food and Drug Administration; OSD, ophthalmic squeeze dispenser; PF, preservative-free (33–39)

Artificial tears are considered the mainstay of dry eye therapy. However, chronic exposure to preservatives present in eye drops can result in exacerbation of dry eye symptoms. To mitigate these side effects, PF formulations in unit dose format are available to prevent the potential risk of contamination during instillation or usage. However, unit dose vials are also associated with several drawbacks. The latest addition of MDPF dosing of lubricant eye drops ensures easy instillation and storage convenience.However, adequate evidence is lacking in terms of the susceptibility to microbial ingress or contamination when used for a longer time period.

Acknowledgments

Medical writing support was provided by Sulekha Shafeeq, PharmD, and Ashwini Atre, PhD, from Indegene Pvt. Ltd. Bangalore, India.

References

- 1. F Stapleton, et al., “TFOS DEWS II Epidemiology Report.” Ocul Surf 15, 334 (2017) PMID: 28736337.

- 2. LL Marshall, JM Roach, “Treatment of Dry Eye Disease,” The Consultant Pharmacist, 31, 96 (2016) PMID: 26842687.

- 3. EM Messmer, The Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Dry Eye Disease, Deutsches Aerzteblatt 112, 71 (2015) PMID: 25686388.

- 4. B Miljanović et al., Impact of Dry Eye Syndrome on Vision-Related Quality of Life, Am J Ophthalmol. 143, 409 (2007), PMID: 17317388.

- 5. M McDonald et al., Economic and Humanistic Burden of Dry Eye Disease in Europe, North America, and Asia: A Systematic Literature Review, Ocular Surface, 14, 144, (2016). PMID: 26733111.

- 6. The Definition and Classification of Dry Eye Disease: Report of the Definition and Classification Subcommittee of the International Dry Eye Workshop (2007). Ocul Surf 5, 75, (2007). PMID 17508116.

- 7. L Jones ,et al., TFOS DEWS II Management and Therapy Report, Ocul Surf, 15, 575, (2017) PMID: 28736343.

- 8. MM Hantera, Trends in dry eye disease management worldwide, Clinical Ophthal, 15, 165 (2021), PMID: 33488065.

- 9. MR Nilforoushan et al.,. Effect of Artificial Tears on Visual Acuity, Am J Ophthalmol, 140, 830 (2005), PMID: 16310460.

- 10. Z Liu, SC Pflugfelder, Corneal surface regularity and the effect of artificial tears in aqueous tear deficiency, Ophthalmology. 106, 939 (1999), PMID: 10328393.

- 11. S Cohen et al., Evaluation of clinical outcomes in patients with dry eye disease using lubricant eye drops containing polyethylene glycol or carboxymethylcellulose, Clinical Ophthalmology. 8, 157 (2014) PMID: 24403819.

- 12. U Benelli, Systane lubricant eye drops in the management of ocular dryness, Clinical Ophthalmology. 5, 783 (2011) PMID: 21750611.

- 13. AD Pucker et al., Over the counter (OTC) artificial tear drops for dry eye syndrome, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (2016) PMID: 26905373.

- 14. C Matossian et al., Dry Eye Disease: Consideration for Women’s Health, J Womens Health. 28, 502, (2019) PMID: 30694724.

- 15. MVMR Ribeiro et al., Effectiveness of using preservative-free artificial tears versus preserved lubricants for the treatment of dry eyes: a systematic review, Arq Bras Oftalmol. 82, 436 (2019) PMID: 31508669.

- 16. M Kahook, The Pros and Cons of Preservatives. Review of Ophthalmology. Published 2015. Accessed March 17, 2021 Available at http://bit.ly/3jbobyc.

- 17. A Hedengran et al., Efficacy and safety evaluation of benzalkonium chloride preserved eye-drops compared with alternatively preserved and preservative-free eye-drops in the treatment of glaucoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. British Journal of Ophthalmology. 104, 1512 (2020) PMID: 32051133.

- 18. N Schrage et al., The Ex Vivo Eye Irritation Test (EVEIT) in evaluation of artificial tears: Purite®-preserved versus unpreserved eye drops. Graefe’s Archive for Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology. 250, 1333 (2012) PMID: 22580989.

- 19. 2007 Report of the International Dry Eye WorkShop (DEWS), Ocul Surf, 5, 65, (2007) PMID: 17508116.

- 20. A Hommer et al., Effect of changing from preserved prostaglandins to preservative-free tafluprost in patients with glaucoma on tear film thickness, Eur J Ophthalmol, 28, 385, (2018) PMID: 29592773.

- 21. DA Sullivan et al., TFOS DEWS II Sex, Gender, and Hormones Report, Ocul Surf, 15, 284 (2017) PMID: 28736336.

- 22. M Rosenfield, Computer vision syndrome: a review of ocular causes and potential treatments, Ophthalmic and Physiological Optics. 31, 502, (2011) PMID: 21480937.

- 23. K Walsh, L Jones, The use of preservatives in dry eye drops, Clinical Ophthalmology. 13, 1409 (2019) PMID: 31447543.

- 24. H Uusitalo H, et al., Benefits of switching from latanoprost to preservative-free tafluprost eye drops: a meta-analysis of two Phase IIIb clinical trials, Clinical Ophthalmology 10, 445, (2016) PMID: 27041987.

- 25. SA Alanazi SA, et al., Effect of Refresh Plus® preservative-free lubricant eyedrops on tear forming patterns in dry eye and normal eye subjects, Clinical Ophthalmology, 13, 1011, (2019) PMID: 31354235.

- 26. D Jee D, et al., Comparison of treatment with preservative-free versus preserved sodium hyaluronate 0.1% and fluorometholone 0.1% eyedrops after cataract surgery in patients with preexisting dry-eye syndrome, J Cataract Refract Surg, 41, 756, (2015) PMID: 25487027.

- 27. L Nasser, et al.,Real-life results of switching from preserved to preservative-free artificial tears containing hyaluronate in patients with dry eye disease, Clinical Ophthalmology, 12, 1519 (2018) PMID: 30197497.

- 28. D Jee et al., Antioxidant and Inflammatory Cytokine in Tears of Patients With Dry Eye Syndrome Treated With Preservative-Free Versus Preserved Eye Drops, Investigative Opthalmology & Visual Science, 55, 5081, (2014). PMID: 24994869.

- 29. N Jaenen, et al., Ocular Symptoms and Signs with Preserved and Preservative-Free Glaucoma Medications, Eur J Ophthalmol, 17, 341, (2007). PMID: 17534814.

- 30. MQ Rahman et al., Microbial contamination of preservative free eye drops in multiple application containers, British Journal of Ophthalmology, 90, 139, (2006), PMID: 16424520.

- 31. A Bagnis et al., Antiglaucoma drugs : The role of preservative-free formulations, Saudi Journal of Ophthalmology, 25, 389, (2011) PMID: 23960953.

- 32. M Safarzadeh et al., Comparison of the clinical efficacy of preserved and preservative-free hydroxypropyl methylcellulose-dextran-containing eyedrops, J Optom, 10, 258 (2017) PMID: 27989693.

- 33. D Marx, M Birkhoff, Ophthalmic Squeeze Dispenser – Eliminating the Need for Additives in Multidose Preservative-Free Eyecare Formulations. Accessed March 17, 2021. Available at http://bit.ly/3wGm2gR.

- 34. Aptar Pharma’s Preservative-Free Multidose Dispenser Approved in the US for Allergan’s REFRESH® RELIEVATM PF Artificial Tear Formulation. Accessed July 30, 2021. Available at https://bit.ly/402vsB7.

- 35. A Campolo et al., A Review of the Containers Available for Multi-Dose Preservative-Free Eye Drops, Biomed J Sci & Tech Res, 45, 36035, (2022)

- 36. L Saidane Ben Petit, B Quaglia, How to deliver preservative-free eye drops in a multidose system with a safer alternative to filters? Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci, 58, 4460 (2017)

- 37. K Ozulken et al., The comparison of bacterial contamination and antibacterial efficacy of the anti-glaucomatous eyedrops with and without preservatives, Journal of Glaucoma and Cataract. 15, 118, (2020)

- 38. ABAK Pure technology in a bottle - Laboratoires Théa. Accessed March 17, 2021. Available at https://bit.ly/405UeQL.

- 39. hydraSense®. An innovative, PRESERVATIVE-FREE, MULTI-DOSE BOTTLE delivery system. Accessed March 17, 2021. Available at https://bit.ly/3WJ8uvG.