Many of you reading this will have implanted thousands, even tens of thousands of intraocular lenses (IOLs) over your career to date, and the last decade has seen some ferocious innovation in optical design. A great deal of that effort has been directed at trying to achieve better, multifocal IOLs, and there’s now a plethora of optic designs from many manufacturers. But have you ever wondered how these IOL designs come to be? What happens behind closed doors at the companies that make them? How do they decide what approach to take? How do they design, test and build them? If so, you’re in luck. We interviewed a team that have done just that. Here’s their story. In 2009, we were part of a team that was given a brief (that unfortunately didn’t self-destruct after reading) to examine all of the optical design concepts that might better suit the needs of patients and surgeons. We were told to go far beyond ophthalmology – to look at all kinds of industries that have technology pertaining to optics. A tall order, and a mission we had no choice other than to accept. With the match struck and the fuse lit, we commenced our “extended depth of focus” (EDOF) research program. Why EDOF? Patients tell surgeons what they want, and surgeons assess, interpret and pass on those requests to the IOL manufacturers.

What we were told was that they wanted better post-procedural near-to-intermediate vision, or in other words, EDOF. Our optical “landscape” research paid off: we came back with a number of viable optical candidates for achieving EDOF in an IOL. However, getting a large ophthalmic product manufacturer to commit millions of Euros of budget to developing an IOL based on some promising EDOF concepts isn’t easy. A financial commitment can only be made based on extensive market research. Which brings us to advisory boards.

Criticism and canapés

Advisory boards are simple in concept: find a group of qualified surgeons who are prepared to share their opinions, coordinate them all so that they’re all in the right venue – usually a small-to-medium sized conference room hotel near a well-served European or North American airport – at the same time, present what you have, and ask them structured questions to gain the benefit of their expertise to guide you on what needs to be done. There are sometimes canapés on offer. They are not glamorous events, but they are essential. We needed to know what complaints surgeons had with existing products so we could avoid those issues and develop a better offering. We also needed to know if we were still on the right track. An example, and probably the most important question that we asked the surgeons was “What would your ideal premium IOL look like?” This attributes list formed our design brief. The surgeons only asked for a full range of vision – for spectacle independence – with no clinically significant contrast loss, and significantly lower halo and glare than existing multifocal IOLs produce. Mission impossible?As a small team of about 10 engineers and scientists, it certainly felt like it was. We have a great working relationship, and produced some great products together, but this was a tall order. At first, it was met with a long list of reasons why it couldn’t be achieved. But soon, we started asking: what if we tried this? What if we did that? We tried anything and everything we could think of. We started cautiously with some rather conservative designs. At first, we managed to avoid dysphotopsia “at any cost,” but there was a cost: the lenses didn’t provide much spectacle independence either. But we kept exploring. Everything we’d learned from the EDOF “landscaping” was brought up and evaluated in team discussions. Eventually, after a lot of spitballing of ideas back and forth amongst us, what we had initially thought was impossible, actually wasn’t. Having said that, it wasn’t easy.

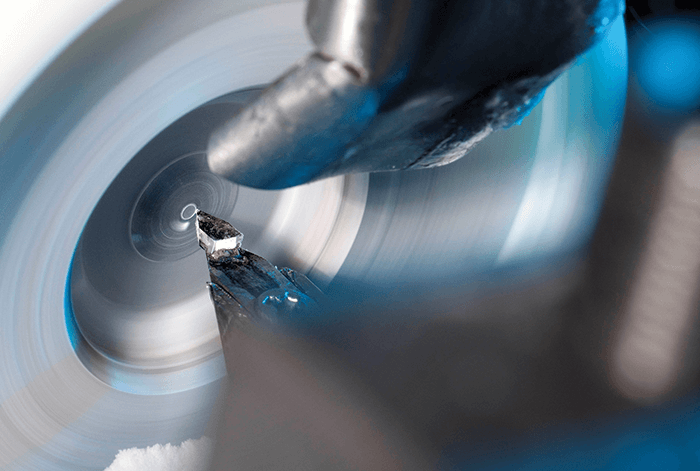

Fifty shades of lathe – and adding to the ensemble

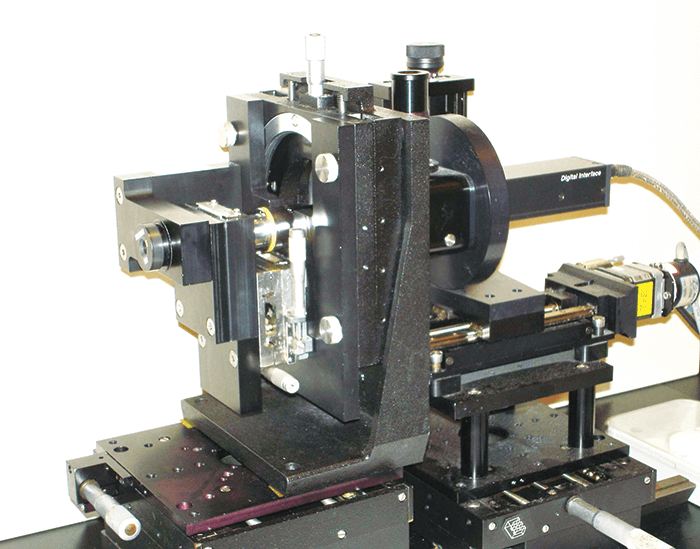

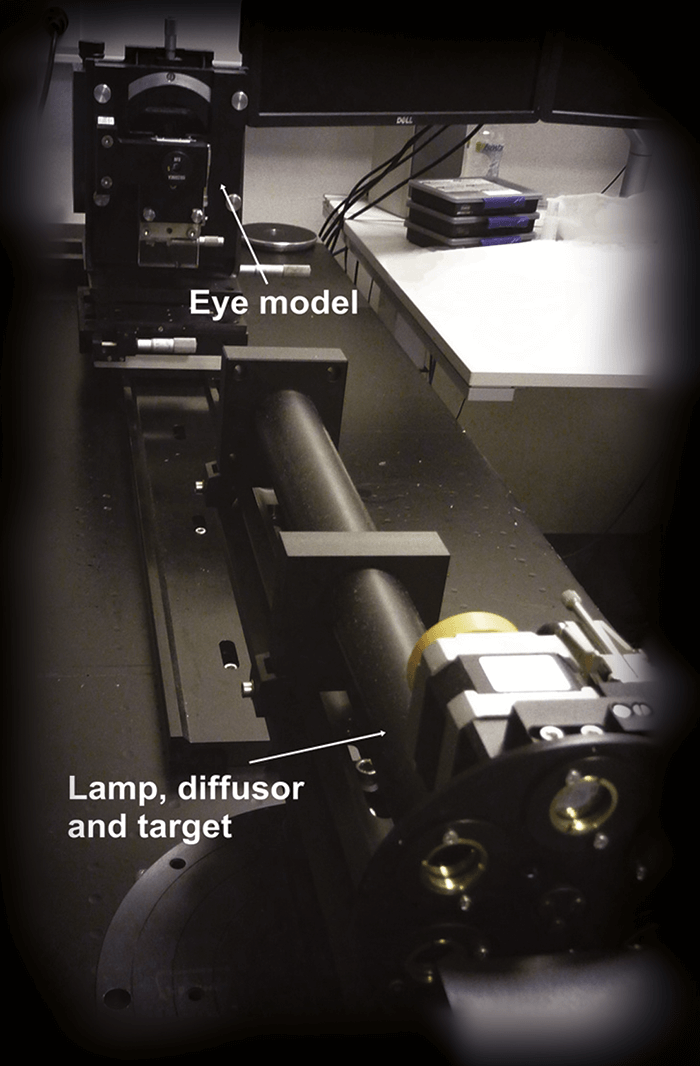

We are lucky: we have the ability to investigate ideas together under one roof, as we have manufacturing, our optics lab, and prototyping next to each other. This meant we could iterate really quickly and get things done – ideal when the ideas were coming thick and fast. In February of 2011, we started a cycle of taking a design, making a prototype (by using a programmable lathe to etch the optics onto the IOL platform), examining it in our optics laboratory (which is not a trivial task – see “Building a Better Optical Bench”), and improving the design. Of course, the consequence of making so many prototypes and assessing many different optical parameters meant that we had reams of data to analyze. We went through this information together as a team. People would say: “Hey! Have you seen this? What do you think of this one? Why is this one like this, and why is this one like that? What if we combined these two?” These were actually very fun, and incredibly productive weeks – keeping up with the quick progression of everything was the hardest, yet the most enjoyable part of the process. In the end, we went through almost 50 iterations before we came up with the final optic design candidates – including the one that eventually made it to the market. The next step was to have the design looked at from regulatory, clinical, and marketing perspectives, so the team grew to include people with those responsibilities too. Together, we picked the design that eventually went into our proof-of-concept clinical trial.The team found out early that standard optical bench setups weren’t able to measure the full optical performance of their new optic designs. Here’s what they did. There are standard ways to measure optics, and we learned early on in our work, that what we (and our competitors) measure on the optical bench isn’t really related to an IOL’s clinical performance – especially in terms of intermediate vision or defocus curve assessments. This meant that our mission wasn’t just developing an EDOF IOL, we had to find ways of measuring and simulating our lenses that were more predictive of clinical performance. At the moment, this is still an issue we face. People take our lenses and measure them on the bench, and say to us, “That doesn’t look the same as it does in your clinical results, are you guys faking it?” Of course we aren’t! We put a lot of effort into looking at how the measurements from the optical bench relate to clinical performance, and some of the critical parameters that you have to put in there in order to simulate the performance of lenses like ours.

What do patients actually see?

The question we asked ourselves was, what should you measure on the optical bench that’s actually reflective of clinical performance? We looked at three issues.“What should you measure on the optical bench that’s actually reflective of clinical performance?”

First, an accurate reflection of the aberrations of the cornea. We found that you absolutely must have chromatic aberration in there. All eyes impart chromatic aberration, and a lot of off-the-shelf optical benches (and therefore a lot of companies) only measure at one wavelength, typically green light. But with these IOLs with advanced optics, it’s very, very important that you’re able to reflect a clinically realistic situation – and chromatic aberration is a very big part of that.

Second, we had to consider that people exist in a world full of white light, not green light – a typical human eye will respond to wavelengths from about 390 to 700 nm – not just the 546 nm that’s the ISO standard wavelength of an optical bench illumination source.

The third aspect – and one that we’ve really come to understand much better in recent years – is real-world eyesight. When people are reading, looking at a visual acuity chart, or even walking around in day-to-day life, they’re looking at things that don’t really reflect what’s on the optical bench. On an optical bench, we measure spatial frequency response (also known as modulation transfer function [MTF]), which essentially looks at high frequency stripes. But that’s not necessarily reflective of how we see the world. Objects are actually made up of all kinds of spatial frequencies, and if you don’t include that information, you don’t get a good reflection of what people are seeing.

Failure to take these aspects of testing into account is the reason why people are measuring our EDOF IOL on the optical bench, and seeing results that aren’t reflective of what we’ve published. There’s currently a huge disconnect between the way certain people, certain companies, and certain standards, tell you how to measure an IOL. This became part of our learning process during the design stage – if you want to create an IOL that can give certain results, optical testing only makes sense if it can accurately predict

real-world performance.

Since then, we’ve published a paper on this topic (1), and it’s been getting a fair amount of attention, even from the standards organizations. Which is good, as people and instrument manufacturers often fall back on standards, even when that standard has been shown not to predict clinical performance! But it’s hard to move people from measurements that are considered “standard” where you just buy an instrument off-the-shelf, into a situation where they have to build their own setup, validate it, and change the entire way that lenses have been measured to date.

The team

Patricia Piers (R&D)Henk Weeber (R&D)

Carmen Canovas (R&D)

Sieger Meijer (R&D)

Peter van Wijk (R&D)

Robin Zonneveld (Operations)

Cyriel Vandeursen (Operations)

Jan Hermans (Operations)

Kendra Hileman (Clinical)

Anne Buteyn (Clinical)

Sanjeev Kasthurirangan (Clinical)

Kristen Featherstone (Clinical)

Roland Pohl (Clinical)

On location in the Caribbean

One of the most enjoyable parts of the Mission: Impossible television and film series was the exotic locations that Briggs, Phelps and Hunt ended up visiting. In our story, the action moved to the Caribbean, specifically in the Republic of Honduras, where our first proof-of-concept clinical trial was run. But we weren’t there to be international women and men of mystery. Our mission, while there, was solely to make certain that our product was both as safe and effective in patients. No matter how much work you’ve done beforehand, and how certain you are that it’s going to be safe and work, first-in-human trials are so very important, that they’re entered into with almost trepidation and definitely with tremendous care. Fortunately, we have a good working relationship with an American cataract surgeon who runs a clinic there, and the facility had everything we needed to test the patients’ visual outcomes. Now, with drugs, clinical trial programs start with safety assessments and slowly move over to efficacy assessments in the later phases. With this IOL, it’s somewhat different: our principal concern is efficacy. Even though we felt that our IOL’s optics were revolutionary and we were excited to see the results in patients, the platform it was built into was a well-known and long-established one: Tecnis. The material, size, shape, surgical process, even the delivery system was consistent with every Tecnis IOL that went before, so in this respect we weren’t venturing into the unknown. This would have been a different story if we were pioneering something like a new accommodative IOL or a brand new platform that was significantly different to what went before. But as the innovation was in the optics and not the platform, the only thing we had to worry about was how it would perform in living, breathing patients. Would all of our efforts pay off?Would it work as well as the optical bench suggested it would? The first investigation was a paired-eye study.

Had the scopes been successfully zeroed?

Just like with the optical lab assessments, the fact that we’d taken a new type of optical approach meant that the biggest challenge during these clinical trials was ensuring that we accurately measured how the lens performed. Once again, we were faced with a world of standard operating procedures that were designed to test either monofocal or multifocal IOLs, when ours was, optically, something else entirely. This meant that our clinical team had to develop new clinical testing methods that could effectively test visual disturbances, binocular effectiveness, and both subjective and objective visual outcomes: “off-the-shelf” testing methods couldn’t cut it. This meant that the clinical trials setup also went through many iterations just to get the information we needed – we’d start off with one set of visual assessment parameters, and we’d need to tweak the test method, or decide we weren’t getting enough information and have to take a fresh approach. At the same time the design team were working through those many iterations of the IOL, the clinical team were going through almost the exact same process, looking for innovative ways to assess performance. Our next journey took us to New Zealand, where we performed a binocular study and assessed patents’ tolerance to astigmatism with the new lens. Again, many of the measurements were new, and again, we had to keep building our clinical methodology too. But it was also very rewarding: reviewing the first-in-man study results, and hearing the enthusiasm of those initial surgeons and patients who let us know that we really were onto something promising. Long story short: our EDOF IOL worked, and we had both the clinical and the laboratory methodologies to prove it. After that, we moved to obtain a CE mark, which we achieved in 2014, and we sell the IOL today under the brand name Tecnis Symfony Intraocular Lens.The next mission

This was an incredible mission: it was exciting to come across new ways to design and apply diffractive optical technology, like combining chromatic aberration correction with extending depth of focus. But the impossible missions never end. We have a new one: to design and build the next IOL. It won’t be a “walk in the park” – but it should be easier. Everything we’ve learned, from the landscaping, lab testing and clinical evaluation is helping us with the next design. We’re always working on how we can simulate things – and every piece of information, from both the lab and the clinical assessments, goes back in to the model, and informs us on what to do for the next lens. We call it the “design circle” – nothing is wasted; we learn something new with every experiment and assessment, and it all goes towards improving the next iteration of our designs. In our world, information is all that matters, and we can’t perform our missions without it.References

- A Alarcon et al, “Preclinical metrics to predict through-focus visual acuity for pseudophakic patients”, Biomed Opt Express, 7, 1877–1888 (2016). PMID: 27231628.