- VMA can be benign, but its seriousness increases as it progresses to VMT

- The standard of care treatment, victrectomy, is both risky and unpleasant, needing weeks of recovery

- Ocriplasmin is an intravitreally-administered protease that dissolves the protein matrix responsible for vitreomacular adhesion and traction

- Not all patients will benefit, but those who do are spared vitrectomy

Vitrectomy is the standard surgical intervention for the treatment of vitreomacular traction (VMT) and macular hole (MH) – completely removing the vitreous often works well. The procedure itself isn’t particularly pleasant and it carries a risk of complications. In addition, the majority of phakic patients who undergo vitrectomy will require cataract surgery within the next couple of years – so if the lens isn’t replaced during the procedure, it will in all likelihood have to be later. If the vitrectomy has been performed to treat MH, a gas bubble is often placed in the vitreous cavity to encourage the hole to close. To keep the bubble in place, many patients have to lie face down for fifty minutes of each hour for up to – and sometimes over – a week. This is obviously uncomfortable and greatly inconvenient.

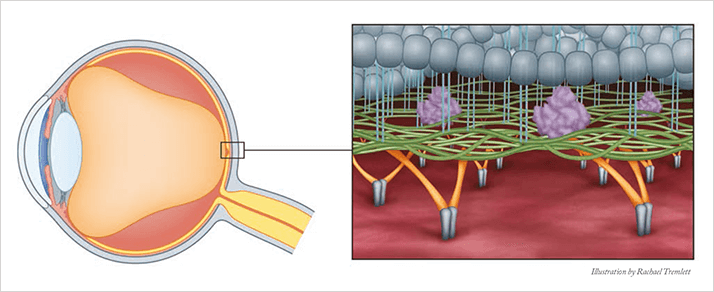

As the eye ages, syneresis and synchisis (vitreous body liquefaction and collapse) commence, a process that, typically, is benign. If concurrent syneresis and weakening of vitreoretinal adhesion occur, the posterior vitreous cortex may separate from the internal limiting membrane. Eventually, this will result in posterior vitreous detachment (PVD); again, typically a benign development. Incomplete posterior vitreous separation, however, leaves residual sites of vitreoretinal and vitreomacular adhesion (VMA). VMA is not ideal. In the early stages its influence on vision is minimal but as it progresses metamorphopsia

can develop.

Tim Jackson, consultant eye surgeon at King’s College Hospital, London explains that, “A continuum exists between VMA, VMT and MH. VMA can progress into VMT, as adhesions to the retinal surface carry pulling forces – traction – that damages the retina. This can ultimately pull a hole, turning it from VMT to MH.” This damage can then lead to tractional macular edema. There is potential for irreversible vision loss, hence the surgical intervention. “If a patient presents with MH, provided it’s treatable, they will usually undergo vitrectomy,” Jackson says. However, as this intervention carries significant risks, and the recovery can be burdensome, the standard of care for VMT has been watchful waiting – delaying surgery until the disease had progressed to a point where it was severe enough for the benefits of vitrectomy outweighed the risks. With MH, the benefits already outweigh the risks, so vitrectomy is performed whenever possible – “we don’t watch and wait with macular hole,” adds Jackson. The standard of care may be about to change. A new therapeutic option, ocriplasmin (Jetrea®, Alcon/Thrombogenics), is now available that might avoid the need for surgery in some cases. Ocriplasmin is a recombinant truncated form of human plasmin, a serine protease that’s best known for dissolving fibrin-rich blood clots. It retains plasmin’s proteolytic activity; when injected intravitreally, it degrades protein components of the vitreous body and the vitreo-retinal interface (VRI), namely laminin, fibronectin and collagen. Thus, it dissolves the protein matrix responsible for VMA and VMT, liquefying the vitreous and, in so doing, ending the disease state (Figure 1). Furthermore, the drug raises the concept of treating VMA before it progresses to VMT – in theory, improving outcomes and minimizing risks.

Fibronectin, laminin and collagen are present throughout the eye, raising the potential for adverse events. Ocriplasmin is a new product, so post-launch safety and efficacy information is sparse. The phase III trial (known as MIVI TRUST) that formed the basis of ocriplasmin’s regulatory approvals provided a good sense of the safety and efficacy of ocriplasmin, and post-marketing studies are said to be consistent with trial data.

Clinical trial data

MIVI TRUST comprised two multicenter, randomized, double-blinded trials (1). It compared the efficacy and safety of ocriplasmin with placebo injections for the treatment of symptomatic VMA. Resolution of VMA, as determined by optical coherence tomography (OCT), was the primary efficacy assessment. By this measure, ocriplasmin was significantly better than placebo injection; 26.5 percent of patients in the ocriplasmin group achieved VMA resolution – with release being achieved within 1 week for 72 percent of these patients. The placebo injection group fared less well; VMA resolved in only 10.1 percent of patients. Similarly, ocriplasmin use was associated with full-thickness MH closure in 40.6 percent of patients at day 28, compared with 10.6 percent of patients who received the placebo injection [p<0.001]). Gains in visual acuity of ?3 lines occurred in 12.3 percent of patients in the ocriplasmin group compared with 6.3 percent of the placebo injection group (p=0.02). Many patients with VMA have only mild to moderate impairment of visual acuity (VA), making a 3-line VA gain hard to achieve.The rate of ocular adverse events was higher in patients treated with ocriplasmin than in the control group (68.4 percent versus 53.5 percent, p=0.001), although ocriplasmin was associated with a reduced risk of serious adverse events, such as MH and retinal detachment. The data showed that across the whole trial population, just over one in four patients who received ocriplasmin experienced resolution of VMA, raising the question: why did some people benefit and others not? Part of the reason is adhesion size, with smaller adhesions more likely to be effectively treated. A MIVI TRUST subgroup analysis showed that VMA resolution occurred with ocriplasmin only 10.3 percent of the time if the adhesion size was greater than 1500 µm, but occurred 33.6 percent of the time if the adhesion size was 1500 µm or smaller (2). A similar story was seen with MH size: if the hole was 250 µm or less, ocriplasmin treatment resulted in resolution 58.3 percent of the time; if it was larger, resolution occurred in 24.8 percent of cases. That knowledge of who will do well is valuable; according to Jackson, “That makes a big difference. The headline figure of 26.5 percent is fine, but if we can hit a 50 percent success rate by selecting the right patients, then ocriplasmin injections become an even more attractive intervention.” So ocriplasmin – like vitrectomy – isn’t for everyone. It appears that two patient populations will benefit most. The first is those with VMT that hasn’t yet progressed enough to justify surgery, as the risks of vitrectomy outweigh the benefits… but the benefit-risk balance of ocriplasmin favors its use. The second is patients with VMT or VMT and MH who require surgery – as if ocriplasmin works, it avoids vitrectomy

Vitrectomy success rates are unaltered by prior ocriplasmin use. Virtually all patients can go home after an ocriplasmin injection, and the MIVI TRUST data shows that if the injection is successful, it will be obvious within a week (and by 28 days at the longest). If ocriplasmin therapy doesn’t succeed, little is lost apart from the cost of ocriplasmin and the clinic visit. Jackson summarizes it thus: “If it works, great, you’ve saved yourself an operation, and if it doesn’t, you’ve not lost anything by trying”. Although post-marketing clinical experience is currently sparse, it looks like ocriplasmin will also save healthcare systems and society money. “You save money by avoiding vitrectomy – but the cost of vitrectomy is not just the surgical cost, it’s also the cost to the patient in terms of recovery time, lost work due to blurred vision after surgery, and the subsequent cataract surgery for those who need it,” Jackson explains. “You also have a quicker visual recovery than you’d see with vitrectomy.”