- Evidence-based medicine is important, but looking at things from a different angle can lead to new discoveries – and young ophthalmologists should be encouraged to do this

- Berger’s space was first described in 1887, but even today its existence is questioned, despite it playing a key role in bag-in-the-lens cataract surgery

- It’s important to think critically about our current knowledge and to remain open to new ideas – otherwise we are doomed to repeat our mistakes

- Creative thinking, collaboration – and taking a break from the caseload – are all crucial to allow young ophthalmologists to develop original ideas that could progress the field

Thinking outside of the box is a beautiful thing. If you want to be an inventor or a pioneer, you have to look at things differently. In my opinion, today’s almost ceaseless focus on evidence-based medicine (EBM) might be holding young ophthalmologists back by stifling their creativity. Of course, EBM is still essential and should remain at the heart of our practice – but it shouldn’t be the only type of thinking we do. Throughout my own career, I have greatly benefitted from adopting a different perspective.

Out of the box… but in the bag

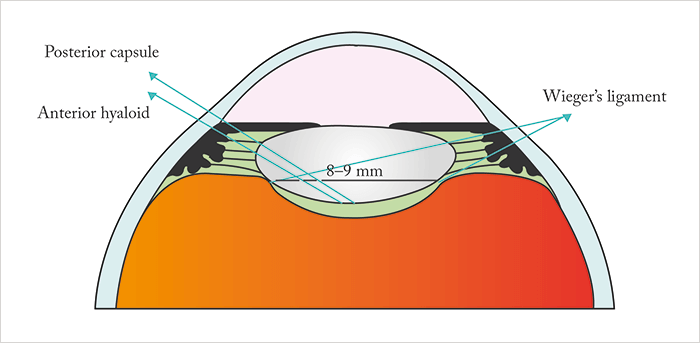

As cataract surgery evolved, much debate was centered on the capsular bag. Initially, we asked: do we keep it or remove it? Later, the consensus became that it was better to keep the capsular bag and leave it untouched as much as possible, keeping the posterior capsule intact, and thus reducing the risk of complications. But a piece of the puzzle was still missing. What many people didn’t know – even though the science was already emerging – was that there is a space between the posterior capsule and the anterior vitreous, known as Berger’s space. I believe that studying this part of the eye’s anatomy can help us better understand the posterior segment complications we see after cataract surgery. My own involvement in studying Berger’s space (Figure 1) began when I was still in training. I met Jan Worst, a brilliant ophthalmologist from the Netherlands who invented the iris claw lens at a meeting of the Belgian Ophthalmological Society. It was back in the 1980s, and the YAG laser had just been introduced; I had used it to treat a patient with a premacular hemorrhage. When I finished giving my case presentation, Jan Worst came on stage, embraced me, and said “You see! This young ophthalmologist understands my work!”At the time, I knew nothing about his work! He invited me to his lab, and I remember that it was in a basement. When he had finished showing me his lab, he took me upstairs to talk over all of the different ideas occupying his incredibly busy brain, showing me slide after slide on the old 35 mm projector he kept up there. Even then, I still wondered: why was he so moved by my presentation? What I didn’t realize at the time was that my patient’s hemorrhage was in the bursa premacularis, a hollow space in front of the macula – the existence of which Jan had demonstrated with some clever studies using white Indian ink. But there was another structure that he was interested in investigating: Berger’s space. It was first described by the Austrian anatomist Emil Berger in 1887, and I asked him if he thought it existed. He said he didn’t know, which bothered him, of course – and he was determined to find out!

Anatomy that isn’t there

Unfortunately, we didn’t find Berger’s space while I was in Jan’s lab, but later he sent me an image of it, with the message “I’ve got it, it’s there!” And now I believe that bag-in-the-lens cataract surgery uses that space (1). When I first suggested this, I received a lot of criticism – and I still receive some to this day. People say to me “During surgery, you are entering the vitreous!” I always tell them, “No, I’m in Berger’s space – and we’ve known about it since 1887!” Even today, most textbooks describe it as a “virtual” space – even though Jan Worst showed it to me back in 1987. Nowadays, we have surgical microscopes with intraoperative OCT, and I can watch what happens behind the capsule in real time (2). After I have emptied the capsular bag of the lens contents during cataract surgery, what do I see? A beautiful space, of course! But the question remains: why is it there and how is it useful? I believe that one answer is that it can help us implant bag-in-the-lens IOLs, but we need to study it further; for example, from my own work, it appears that dysgenesis of this surface results in a specific kind of congenital cataract.Swap cases for collaboration

Collaboration is another crucial component of discovery – you need to find the right people to help you, because you never achieve as much alone as you do with other people. Yes, you want to work with other ophthalmologists, but also people from other disciplines, such as physics and engineering. A multidisciplinary team can provide a range of fresh perspectives to your work, which is a huge advantage. The beauty of a university setting is that you have all these different people gathered together, and you can network and find the right people to help you meet your goals. However, learning to “speak the same language” is necessary to be as creative and productive as possible – and building that bridge between disciplines can take years, so it’s important to start early. I’ve learned a lot from studying these structures in the eye and arguing the case for them with my colleagues. I always tell my students – think! Remember that everything in the body is there for a reason. When you see something unusual… start asking questions, and see if anyone in the literature is asking them too. Don’t accept conventional wisdom. If everybody says that something doesn’t exist, that doesn’t make it true – it might even already be in the literature. In medicine, as in any field, we sometimes make our mistakes over and over again, in papers, books and lectures. We must always remain critical. And I also think we need to give our young ophthalmologists more time to get creative. If you’re constantly seeing cases and operating, there is little time for other pursuits. So stop, take a deep breath, and make the time you need to work towards answering your questions.Marie-José Tassignon is Chief and Chair of the Department of Ophthalmology at Antwerp University Hospital, Antwerp, Belgium. She holds intellectual property related to bag-in-the-lens IOLs, and is a consultant for Théa, Zeiss and PhysIOL.

References

- M-J Tassignon, “Don’t fear the posterior capsule”, The Ophthalmologist, 5, 29–31, (2014). Available at top.txp.to/issues/2014/402. M-J Tassignon, S Ní Dhubhghaill, “Real-Time intraoperative optical coherence tomography imaging confirms older concepts about the Berger space”, Ophthalmic Res., 56, 222–226 (2016). PMID: 27352381.