- Early multifocal IOLs were something of a mixed bag – variations in vision caused by pupil diameter and problems achieving good intermediate vision made true spectacle-independence a challenge

- The long-term data on mixing refractive and diffractive IOLs produced good results and revealed important lessons to apply to newer mIOLs

- Refractive accuracy, achieving good near and intermediate vision, and careful patient selection are crucial factors to take into account

- Surgeons who have achieved good results (despite the limitations of past mIOLs) should see even greater successes in the future

When multifocal IOLs (mIOLs) were first introduced, the idea of giving my patients good vision without glasses really excited me. But as I soon discovered, first and even the second generations of presbyopia-correcting IOLs weren’t without their limitations.

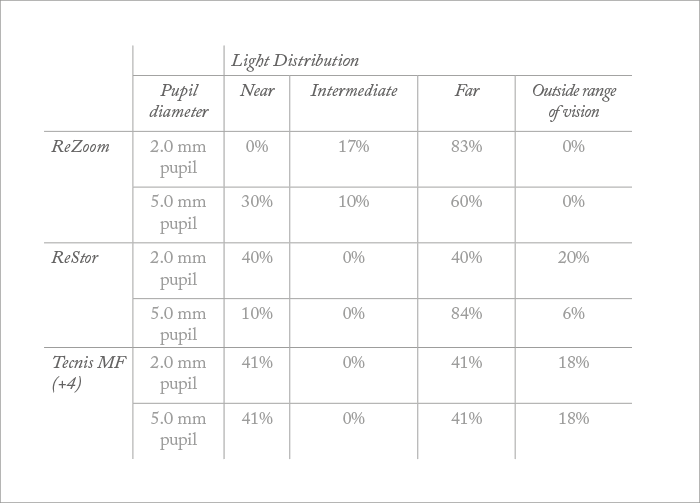

The variation patients experienced in their vision as their pupil diameter changed was a major challenge. At a pupil diameter of 3.0 mm, most mIOLs work very well. But our patients don’t live in a static world – light intensity changes throughout the day and in different environments – so their visual experience with certain IOLs can change dramatically. Some designs also result in significant loss of light that is outside the range of vision at larger or smaller pupil sizes (as described in Table 1). The other limitation of many of the earlier mIOLs was intermediate vision. Vision at about 70 cm is critical for many daily tasks, such as using computers or handheld devices like smartphones and tablets. Finding a way to overcome this limitation and provide truly spectacle-free vision for my patients was the reason I decided to try mixing refractive and diffractive mIOLs.

Long-term lessons

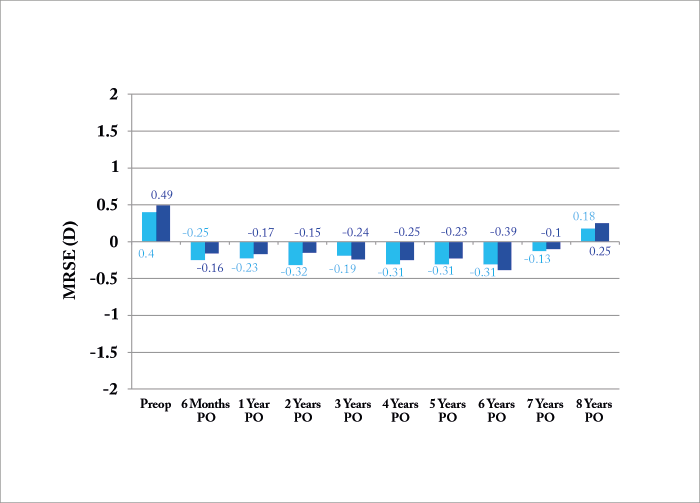

I now have eight-year results of the mix-and-match approach in 52 patients (32 female and 20 male, 104 eyes). The average age of the patients studied was 69.33 ±11.35 years, and all returned to the clinic annually for follow-up examinations. These patients all had a refractive mIOL (ReZoom, Abbot Medical Optics) implanted in one eye, and a diffractive multifocal (Tecnis Multifocal, Abbott Medical Optics) implanted in the other. Patients with pupils >5.0 mm in dim light were excluded from the study, because the lens used in this study does not perform well at larger pupil sizes. Eyes with astigmatism of more than 0.50 D were also excluded.So far, the results I’ve seen are very promising – eight years postoperatively, the best-corrected visual acuity (VA) outcomes of these patients are stable, with no variation. Mean manifest refraction spherical equivalent (MRSE), which is a useful way to demonstrate postoperative refractive results, was approximately -0.25 D, and has been very consistent throughout the eight-year follow-up period (see Figure 1). Finally, and most importantly, patient satisfaction was very high. This method isn’t perfect though, as monocular near vision was J3 to J5 at all time points – which is not as good as our typical experience with bilateral diffractive multifocal IOLs. However, with both eyes open, 94 to 95 percent of patients said they could function without glasses at intermediate distance, which was the goal of mixing these two different IOL types in the first place.

Top tips for refractive success

Today, we have new and better options to achieve uncorrected vision at all distances with fewer visual compromises, eliminating the need for diffractive/refractive combinations. But there are some lessons from this long-term data that remain relevant today.1. Refractive accuracy is key

The patients in this study were very happy with their vision following IOL implantation, because they achieved plano results that allowed them to have great distance vision. In refractive cataract surgery in general, and when using mIOLs in particular, performing precise biometry and excellent surgery, in order to get a plano result, are crucial steps. Some years ago, Jack Holladay explained the relationship between pupil size and quality of vision (1). With a small pupil (<5.0 D), minor residual error of -0.50 D after surgery has little effect on VA, and the patient will still have VA of about 20/24. But that same amount of residual error provides a theoretical best acuity of only 20/30 if the pupil is 7.0 mm, which is possible in younger refractive lensectomy patients. With a diffractive mIOL, the penalty doubles, meaning that just -0.50 D of residual error can reduce vision by a full two lines – something that most patients will definitely notice. If you combine residual error with larger pupils in a mIOL patient, you’re creating a recipe for dissatisfaction and complaints. “Get a plano result.” This might be a direction that is easy to give and difficult to follow, but make no mistake that it is absolutely mandatory for spectacle-free vision, and a happy patient.

2. Never ignore intermediate vision

In this study, the refractive IOL provided far and near vision, while the diffractive provided far and intermediate vision. The results demonstrate that the aim of ensuring that patients get both near and intermediate vision was achieved. A great advantage of all the newer, advanced-technology IOLs, such as lower-add diffractive multifocals, trifocal IOLs, and mIOLs that extend the range of vision, is that they provide much better intermediate vision, again highlighting the importance of this gap in older technology.3. Know your technology – and know your patients

Although today’s presbyopia-correcting IOLs are more forgiving and have fewer visual tradeoffs than the lenses we had eight years ago, it’s just as important now as it was then to understand how they work, and to carefully select patients who will benefit from these lenses. For example, it is very unlikely that you’ll achieve a good result using a mIOL with a patient with ≥0.75 D of corneal astigmatism – you need to correct the astigmatism with incisional or laser ablation methods, or perhaps opt for a toric lens instead. Understanding the degree to which new lenses are pupil dependent, and how that might affect visual performance for patients with unusually large or small pupils is another consideration. A big disadvantage of the refractive lens used in this study is that it may not provide high quality far vision in patients with larger pupil sizes, because of an increase of halos. In my practice, we have decided not to implant them in patients with pupils of diameters greater than 5.0 mm.Past lessons for future success

Through different focal points, better optics, and new light distribution strategies, newer generation IOLs are beginning to address the challenges of intermediate vision and pupil independence that previously made it necessary to take a mix-and-match approach. They may also be able to address some of the additional challenges we see with mIOLs, such as reduced contrast sensitivity, and reduced available light.I believe that these new technologies will allow many more patients to take advantage of presbyopia-correcting IOLs. And even though previous generations of these lenses had some downsides, surgeons who have learned from the challenges and limitations of the IOLs of the past, and achieved successful outcomes despite them, are likely to find even greater success in the future. Matteo Piovella is Medical Director of CMA (Centro Microchirurgia Ambulatoriale) in Monza, Italy, and serves as President of the Italian Ophthalmological Society.

References

- JT Holladay et al., “The relationship of visual acuity, refractive error, and pupil size after radial keratotomy”, Arch Ophthalmol 109, 70–76 (1991). PMID: 1987953.