At A Glance

- Professor Twinamasiko is the founder of the Mbarara University of Science and Technology Department of Ophthalmology, responsible for training ophthalmologists from east African countries and beyond

- He also started a residency program with the Ruharo Eye Centre, and admitted the first resident in 2003

- Professor Twinamasiko managed to secure funding for the department, and develop the infrastructure

- In May 2019, the largest group of graduates since its conception will leave the department.

Mbarara University of Science and Technology (MUST) is not the largest university in Uganda – it is not even close. Set over two campuses on the banks of the Rwizi River in southwest Kampala, MUST has just 3,000 students, yet is recognized as one of the best training institutions in East Africa – teaching ophthalmologists from Uganda, Burundi, Democratic Republic of Congo, Ghana, Guyana, Rwanda, Sierra Leone and South Sudan. The reason why can be attributed, almost entirely, to one professor: Amos Twinamasiko.

Twinamasiko founded the MUST Department of Ophthalmology in 1993 and has been devoted to it ever since. He transformed MUST from a makeshift office to what is now a free-standing eye hospital, providing excellent patient care, a vibrant residency program and multi-year funded research programs in microbial keratitis and diabetic retinopathy.

In Sub-Saharan Africa, one of the most commonly referenced human resources challenge is the unequal geographic placement of providers, especially of specialists. Twinamasiko could have stayed in the capital, Kampala, where he qualified in medicine and ophthalmology, but he chose to return to his home region and commit himself to the public sector.

His decision shaped the lives of more than just his patients. Arlene Bobb-Semple, winner of the 2017 ophthalmology resident research award – a prize recognizing research among the regional College of Ophthalmology of Eastern, Central, and Southern Africa (COECSA) – credits her success to Twinamasiko.

“When I was a student, I admired his excellent work ethic and his humility,” she says. “I aspire to be an exemplary ophthalmologist who can leave a legacy in my country, upholding my ethical duties and responsibilities while remaining humble.” Bobb-Semple went on to train as a vitreoretinal surgeon in Tanzania, and has since returned to Guyana to practice. Day in day out, she maintains the philosophy and approach to patient care that Twinamasiko instilled in her and all of his mentees.

As the Department nears its 25th anniversary – and as Twinamasiko approaches his retirement – Bobb-Semple and fellow mentees, Simon Arunga and Tu Tran, interview him about his inspiring career.

What were the major obstacles for establishing and expanding the department?

AT: At the start, I felt like being asked to cultivate the fields without any tools. It was up to me to figure out how to take care of patients. Infrastructure was lacking. We had one room as an office that I shared with another lecturer, and another room that doubled as the clinic and teaching space for medical students. In time, we were given a bigger room, and later a second room when I took on an administrative role. Eventually, the government provided a fair amount of ophthalmic equipment, but we could not deploy it without an operating theater space.

Recruiting ophthalmologists was another major challenge. Not only was there a ban on recruitment of additional faculty because of a shortage of funds, the job contracts that did exist were so poor that nobody would apply. For several years, I was the only full-time faculty member. To train medical students and residents, we depended on the grace of Dr. Keith Waddell and the other ophthalmologists at Ruharo Eye Centre, which is a storied, church-based eye hospital a few kilometers away from MUST.

I realized the only way to attract and retain ophthalmologists was to start a residency program. Ruharo Eye Centre generously offered to host residents for in-service training, and we admitted the first resident in 2003.

To expand the faculty beyond just me, Christoffel-Blindenmission (CBM) agreed to support the first one to two years of faculty salaries, then transition them to the university payroll. One of the first to join was Professor Kenneth Kagame. Later, the fourth faculty member was added when MUST hired a resident who graduated from our program.

In July 2013, the Ophthalmology Department moved into the Mbarara University and Referral Hospital Eye Centre (MURHEC). This was a game changer that could have not been achieved without the Eastern Africa College of Ophthalmologists (EACO), which has since merged with the Ophthalmological Society of Eastern Africa (OSEA) to form COECSA. The EACO received a European Union/Sightsavers/Light for the World grant that included infrastructure development. This grant allowed us to establish an eye hospital with space for outpatients, inpatients, operating theaters, investigations, imaging and teaching. It opened up opportunities for expansion that we never had before.

With new facilities, we could offer a wider variety of eye care services to a greater number of patients, we could attract more applicants to the residency program and more international collaborators, who have helped in the training of both faculty and residents, provided more equipment, and opened up opportunities for research collaborations. Of course, not all is perfect. A major challenge is the shortage of dedicated morning, evening and night shift nurses, which greatly affects quality of care.

During the Department’s first decade, donors turned you down because they didn’t see the need for another eye service when the well-established Ruharo Eye Centre was nearby. What changed?

We have to be thankful for the former EACO. Approaching international donors as a united consortium of university eye departments made all the difference. Indeed, potential donors initially felt that there was no need to develop another eye unit in Mbarara when Ruharo was doing so well. Most donors thought training ophthalmologists was too expensive and the focus should be on training mid-level providers.

In 2000, I was invited to a WHO meeting that brought together representatives from different university eye departments and major NGOs involved in eye care. The meeting resolved in a call for increased output of ophthalmologists and harmonization of quality, but the NGOs would not entertain funding requests from individual institutions. Hence, EACO was launched in 2005 to mobilize financial support and harmonize training programs. For the first time, the eye departments came together to present a united proposal for the development of ophthalmology departments at universities in East Africa. Even the oldest residency program at University of Nairobi needed support to develop further.

Establishing an eye hospital to house an academic ophthalmology department has broadened our horizons massively, leading to a more self-sustaining system. We can now train and retain ophthalmologists within Southwestern Uganda, leveraging our new capacity to build partnerships with the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints, Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary, Orbis, and the Fred Hollows Foundation. We have also sustained outreach for high volume surgical camps with support of the Pentecostal Church in the USA.

Acquiring the funding for infrastructural development was a battle, but implementing the project was also taxing on you. Can you tell us about that experience?

It took a high degree of vigilance and persistence. I served as an accounts auditor, architectural consultant and even a quantities surveyor. I cared for our eye hospital as if it was my personal home. Towards the latter stage, 90 percent of the funds were paid but only 60 percent of the promised work had been done. After an audit of the books, we concluded that the consultant and contractor had conspired to defraud the funding agency.

Our construction project was not the only one succumbing to this, but to overcome this obstacle, our selfless friends at the Kilimanjaro Christian Medical College (Moshi, Tanzania) gave us a share of their allocated grant budget for construction. This allowed us to finish the building and purchase furniture, equipment and supplies.

Any construction project involving multiple beneficiary countries, international donors and diverse stakeholders is susceptible to being slowed by bureaucracy. I must congratulate the MUST university administration for working expeditiously to seize this opportunity. They promptly signed the commitment to participate in the project, allocated us land, and supported us at every stage of the construction, so that we were able to get the most benefit from the project. I will forever be grateful.

You have welcomed many international collaborators over the years. What makes a successful partnership?

For a collaboration to work well, it must be mutually beneficial. Partners from more well-resourced institutions may mobilize resources and provide sub-specialty and technical support. In return, they enhance their professionals by exposing them to a wider working environment, which provides them with opportunities to expand their research fields and to make a greater contribution to humanity. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and the National Health Service Bristol Hospitals are the most recent examples; they procured posterior segment lasers for us, and will bring their specialists to train our faculty and residents.

In the future, foreign specialists and trainees can rotate through our department to provide this treatment. Lastly, the European Union authorized this project in 2009, not long after the 2008 Great Recession. What we have been able to achieve is a reminder of what good their support has done for humanity, despite the challenges and instability their nations faced.

What were the most influential moments in your early career?

My first career turning point was moving to the Church of Uganda Kisiizi Hospital in April 1981. I qualified as a doctor from Makerere University in 1980, during some of the most difficult days of Uganda. The country was transitioning from Idi Amin’s rule and several government changes in a short period. Like all other sectors, the medical services were run down. It was difficult to practice medicine in the public sector and Kampala was very insecure. While on vacation, I rotated at a church-based hospital in southwestern Uganda: Kisiizi Hospital.

I learned that they were looking for a Ugandan doctor to join the two expatriates running the hospital. I was attracted to the superlatively high-quality services they offered and the positive attitude they had, even under difficult conditions. I requested to be posted to Kisiizi after medical school, and it was there I learned many aspects of medicine and surgery.

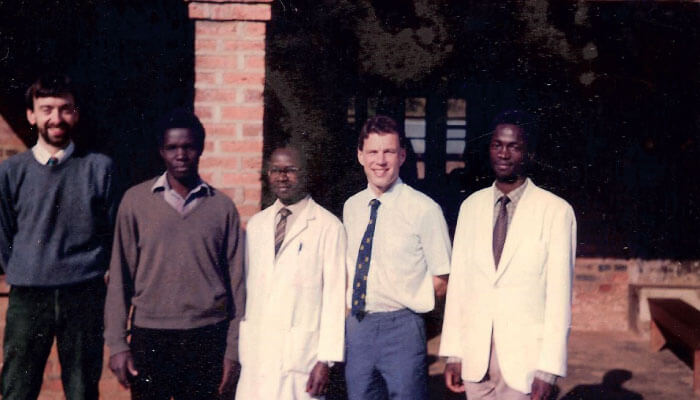

While contemplating how to further my career, we were visited by an ophthalmologist from CBM, the late Dr. Joseph Taylor. He offered me a six-month trial training as a cataract surgeon in Mvumi Hospital in central Tanzania under the enthusiastic lead ophthalmologist, Dr. Allen Foster. Realizing the shortage of ophthalmologists in East Africa, I saw it as an area where I had the potential to make a real impact. I then returned to Kisiizi Hospital to strengthen the eye care services we already offered. We ran many mobile outreach clinics and surgical camps throughout southwestern Uganda and it was then I made up my mind to train as an ophthalmologist.

The second career-turning point was my move to MUST. CBM sponsored me to undergo one-year training at the University of Zimbabwe, and later residency training at Makerere University. Upon finishing, I was committed to move to Mbarara to work at Ruharo Eye Centre. CBM determined Ruharo was the optimum base to provide coverage for the Southwestern region, but Ruharo was not ready to receive me.

By chance, I discovered MUST needed an ophthalmologist. I hesitated slightly because working conditions in government hospitals at that time were notoriously bad for healthcare providers. Nevertheless, I had no desire to work in Kampala. So, with my heart set on rural Uganda, I moved to Mbarara and became the sole MUST ophthalmology faculty member in December 1993. The first piece of equipment I used was borrowed from Kisiizi Hospital.

What advice do you have for young ophthalmologists in Uganda and other low- and middle-income countries?

I should start by saying there are greater opportunities for training and career improvement than there were 25 years ago. In Uganda, the potential for improved welfare is also rising with renewed interest in health insurance. However, the profession is also becoming more demanding, with the emphasis shifting from quantity to quality. For those in training institutions, the focus is now on workload analysis. There is also increased emphasis on having more formal research training through PhDs and publications.

Ophthalmology is still one of the marginalized specialties in Uganda. We need to keep pressing to raise the profile of ophthalmology, as we have tended to sit back and let other specialties and non-healthcare professionals determine our course. Ophthalmologists should advocate for the elevation of health care in general, with ophthalmology having a role in public health.

Much as there is potential for better earning capacity for ophthalmologists in the near future, the practice of medicine always involves sacrifice. Even as a more senior practitioner, you will always find times where you are required to serve much more than you will be remunerated for directly. But do not worry; you will be blessed in other ways. Always remember to find a career and other aspects of life like family, health, and faith. In the final analysis these determine the quality of your life.

In 2014, you gave up your position as Head of Department. What motivated your decision?

I transitioned the Head of Department position to a younger ophthalmologist: Dr. John Onyango. It was appropriate because I had a colleague who was extremely qualified to take over and thus, share the responsibility, so I could pay attention to other aspects of professional life that had lagged behind because of my administrative duties. It is very gratifying to see the department running at a faster pace under such young, enthusiastic leadership.

As my retirement approaches, I feel comfortable that the department is in good hands and supported by active ophthalmologists who will be able to take it to greater heights, especially with the ever-increasing opportunities for international collaborations. I am confident that, under Dr. Onyango’s leadership, we will realize the vision of MUST Ophthalmology Department to become a center of excellence for training eye care professionals and research.

Last year, we treated nearly 9,000 patients, operated on 464, and examined 1,513 patients in outreach. In May 2018, we graduated a class of six residents – the largest in our history. We will also graduate six in May 2019. The future is bright.