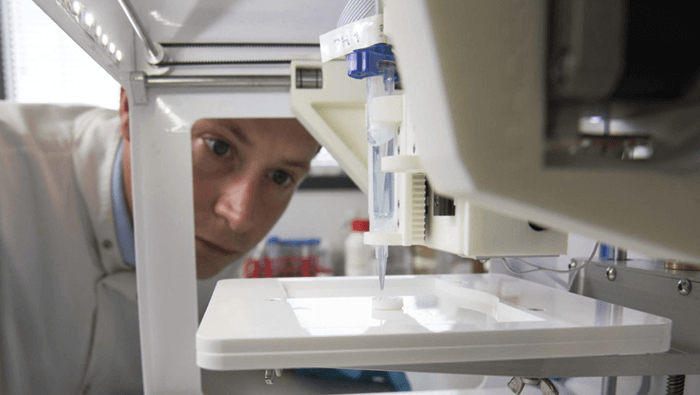

Corneal transplants are among the most common solid tissue transplants – over 30,000 are performed each year in the US alone (1). But with around 10 million people in need of transplants globally, the number of donor corneas cannot meet cut demand. Now, a team at Newcastle University in the UK has succeeded in 3D-printing a human cornea equivalent (2). The proof-of-concept study, led by Che Connon, Professor of Tissue Engineering, mixed stem cells from a healthy donor cornea with alginate and collagen to create a “bio-ink”, which was 3D printed in concentric circles to form the shape of a cornea in less than 10 minutes. We spoke with Connon to find out more...

Why 3D print a cornea?

I’ve been working in corneal biology for over 20 years, and it has recently been observed that stromal cells can be influenced by the shape of the cornea – specifically, a curved surface creates alignment of these cells, and alignment is important for maintaining the transparency and function of the cornea. We believe that the shape of the cornea is not only important for refraction and so on, but also for the way the cells behave. So we needed to find a way to create a curved tissue to facilitate the right cell behavior as well as its refractive properties – and 3D printing has been gaining a lot of attention recently, so we decided to try it. One of the benefits of this approach is that you can have fine control over the final product you produce, and you can produce a tissue with multiple features. We have been looking at the mechanical properties of the limbus and the effect of stiffness on epithelial differentiation – and from our understanding, on a printed cornea we wanted to create a different degree of stiffness at the edge than in the center.How did you create your “ink”?

This was probably our biggest challenge – we needed a “bio-ink” with which to print our 3D construct, and it needed to have specific properties. It needed to keep the stromal cells alive, and be extrudable, so that it could get through the printer needle. Finally, once printed it needed to retain its structure and remain stiff. We achieved this using a unique combination of collagen – which is, of course, the main structural component in the cornea – and alginate, which is a polysaccharide extracted from seaweed.How do you envision the 3D-printable cornea being used?

We hope that eventually the corneas will be printed on demand, as 3D printing offers this flexibility, and the machines we’ve been working with are relatively cheap. We’ve been collaborating with the Newcastle University spin off company, Atelerix, which offers a hydrogel that keeps cells alive at room temperature for several weeks in a sealed storable tube. So thinking ahead, we could see our technology on the shelf in the doctor’s surgery. One day, you could potentially have a printer in the corner of your surgery – simply plug in a tube of bio-ink containing the live cells, creating the tissue you need on the spot!References

- National Eye Institute, “NEI Support for Corneal Transplantation”, (2011). Available at: bit.ly/NEICornea. Accessed June 6, 2018. A Isaacson et al., “3D bioprinting of a corneal stroma equivalent”, Exp Eye Res, 173, 188–193 (2018). PMID: 29772228.