The human eye has somewhat limited contrast sensitivity, but those perceptions of differences that we do possess help us to recognize and differentiate objects. To assist, contrast adaptation changes with lighting conditions, which is why we experience short adjustment periods when a bright light is switched on or when we enter a dark building on a bright summer’s day. That speed of adaptation, especially from light to dark, is known to degrade with age. But how is it affected by glaucoma? The disease is characterized by progressive neurodegeneration of retinal ganglion cells, structural changes at the optic nerve head and optic nerve lesions (1), and two logical neurological consequences of this damage are contrast adaptation and discrimination. So a group of researchers in the University of Melbourne recently assessed the effect of glaucoma (and aging) on rapid contrast adaption (1).

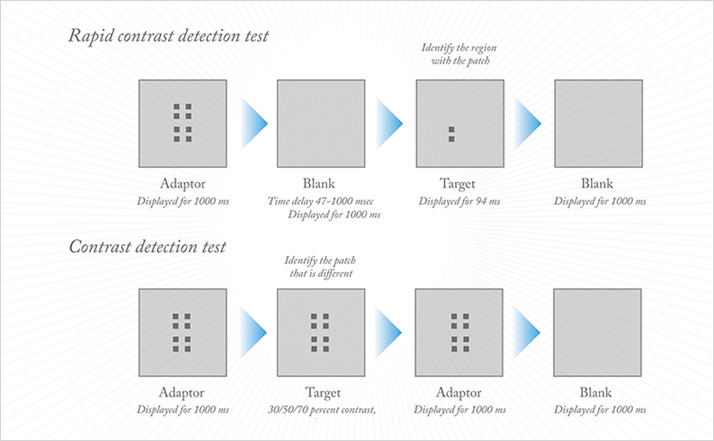

The team recruited three subject groups: fourteen subjects with glaucoma (aged between 58 and 77 years); seventeen age-similar controls (aged 50 to 72 years), and nineteen “young individuals” aged between 20 and 31 years. Rapid contrast detection was assessed using a psychophysical method to measure the time-course of contrast detection recovery on a specially-calibrated computer monitor. Subjects were shown a Gabor patch for a short (94 ms) period that’s most relevant for natural visual tasks, and asked to identify which quadrant of the computer screen it was displayed in (Figure 1). Contrast discrimination was determined using the same equipment; subjects were briefly shown four Gabor patches, with one having a different contrast to the others, and asked to identify which patch was the odd one out (Figure 1).

What the researchers found was that test subjects with glaucoma required far greater levels of contrast to detect and discriminate the Gabor patches compared with the age-similar and younger control subjects, and it took them longer to perceive the patches. Thus glaucoma significantly impairs rapid contrast adaptation. In subjects without glaucoma (that is comparing young versus old), aging was associated with increased unadapted contrast thresholds. Thus it gets harder to discriminate contrast as you get older. The research also confirms just how central the retinal ganglion cells are for contrast sensitivity. They are a basic essential of vision. Research into their repair or replacement could be a key part of successful future treatment for glaucoma.

References

- J.J. Lek, A.J. Vingrys, A.M. McKendrick, “Rapid Contrast Adaptation in Glaucoma and in Ageing”, Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci., Epub ahead of print (2014). doi: 10.1167/iovs.13-13229.