The link between intestinal microbial flora and autoimmune disease is well known, with multiple animal studies showing links between gut bacteria and arthritis (1), colitis (2) and nerve sheath demyelination (3). Now it turns out that uveitis can probably be added to that list (4). R161H transgenic mice are a particularly good animal model for studying the disease processes that underpin uveitis; their possession of T-cells specifically engineered to react to the conserved retinal protein, interphotoreceptor retinoid-binding protein (IRBP), allow them to spontaneously develop autoimmune uveitis. Researchers at the National Eye Institute used the R161H mice to try to address a particularly puzzling question: if the proteins targeted by these modified T-cells in R161H mice exist only in the immune-privileged space of the eye, then how do the attacking T-cells become activated and cross the blood-retinal barrier?

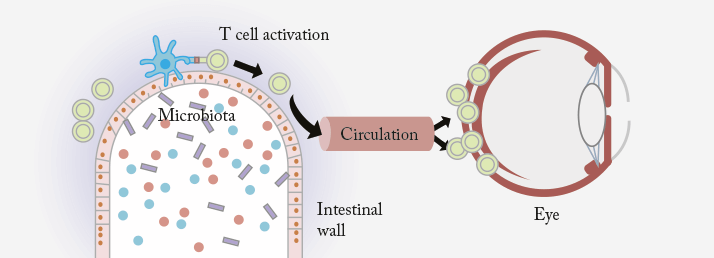

The researchers examined the mice before they showed any signs of uveitic disease, and noted a greatly elevated expression of autoreactive T-cells in their intestines – and it turns out that those T-cells were capable of producing IL-17A, a well known pathogenic cytokine in autoimmune uveitis. Hypothesizing that bacteria in the gut might be involved in T-cell activation, they tried raising mice in a germ-free environment where they were unable to acquire normal intestinal microbiota. What they found was that although some signs of uveitis were present in those mice under these conditions, it was very mild in comparison to mice raised in a normal environment. When the mice were moved from a germ-free to a regular environment, they fulfilled their destiny to develop full-blown uveitis. It’s not yet certain exactly how intestinal microbes prime T-cells to attack the eye, but the researchers suggest that the microbes may produce a molecule similar to IRBP. When the T-cells are exposed to this molecule, they begin seeking out and attacking it in other places – including in the retina (Figure 1). That theory was reinforced by another experiment the scientists conducted, exposing T-cells to a mixture of proteins extracted from gut bacteria. After intraperitoneally injecting those activated T-cells into normal mice not predisposed to uveitis, they developed a uveitic phenotype.

If this research can identify the bacterium, molecule or process that prompts T-cells to target the tissues of the eye, then perhaps one day we might have an effective and targeted therapy for ocular inflammation that could replace corticosteroids – and the collection of adverse events associated with chronic usage.

References

- HJ Wu, et al., “Gut-residing segmented filamentous bacteria drive autoimmune arthritis via T helper 17 cells”, Immunity, 32, 815–827 (2010). PMID: 20620945. WS Garrett, et al., “Enterobacteriaceae act in concert with the gut microbiota to induce spontaneous and maternally transmitted colitis”, Cell Host Microbe, 8, 292–300 (2010). PMID: 20833380. K Berer, et al., “Commensal microbiota and myelin autoantigen cooperate to trigger autoimmune demyelination”, Nature, 479, 538–541 (2011). PMID: 22031325. R Horai, et al., “Microbiota-dependent activation of an autoreactive T cell receptor provokes autoimmunity in an immunologically privileged site”, Immunity, 43, 343–353 (2015). PMID: 26287682.