- You might admire – and even aspire to have – the skills of ophthalmology’s rock stars, but where do you start?

- No amount of skin suturing or bowel retracting as a medical student can prepare you for microsurgery inside an eyeball – simulator use and plain old study are cited as the keys to success

- But simulated surgery and actual surgery are two very different beasts – and the transition from one to the other can be terrifying

- Here, I “live-blog” the terror I felt in my first cataract case!

I lost points on instrument velocity and eye centration. Although my capsulorhexis was improving, I still occasionally shot my instruments wildly across the eye or torqued everything out of view. A computer simulated female voice would repeat, “Do not operate without the red reflex,” sometimes so frequently, she would fail to finish the first scolding before starting in with the second. “Do not operate without the—Do not operate without the red reflex.” Eventually, I expected her to get tired of providing constant reminders and go completely off script: “Excuse me, Doctor. Please take your instruments out of the bionic eye. This is embarrassing. Have you considered a non-surgical specialty? It’s not too late!”

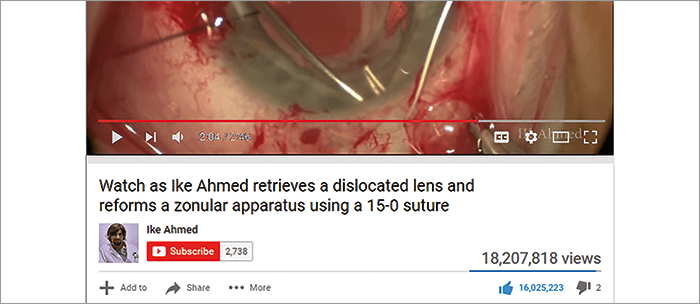

For most residents, the EyeSi simulator provides the most realistic cataract surgery experience. It’s a point of emphasis during residency interviews. Every tour includes a quick glimpse of the beloved simulator. During my first year of residency, I spent hours creating a little flap with my fake cystitome, followed by a fake capsulorrhexis with my fake Utrata forceps. I would play games on the simulator designed to improve the dexterity of my left hand, maneuvering two virtual chopsticks into a tiny dumbbell and holding it there until it turned green. I would either be rewarded or punished with a grade based on my performance, all with the goal of preparing me for the real deal. In hindsight, the simulator training actually led to much more irrational thinking and anxiety than surgical skill proficiency. I remember thinking, “If I can’t corral these little spheres into a tiny circle in the middle of this virtual eye, how will I ever be able to divide and conquer a nucleus?” In my mind, as a first year resident with no ophthalmic surgical experience, this was a completely reasonable concern. Why do we do this training? Some studies have shown a decrease in phaco times, fewer intraoperative complications, and a shorter learning curve in residents who trained with a simulator (1). Ultimately, it’s our best opportunity to prepare for a surgery that medical education is unable to. No amount of skin suturing or bowel retracting as a medical student can prepare you for microsurgery inside an eyeball. Because of the difficulty with providing pre-residency training, there is so much self-doubt surrounding our first handful of cataract surgeries. Is it normal to look this way? Is it normal for this to be so difficult? Shouldn’t my tremor at least help with nucleus disassembly? Throughout residency, we are inundated with videos of beautiful surgeries on social media. We see YouTube videos of famous surgeons doing extraordinary things inside an eye. “Watch as Ike Ahmed retrieves a dislocated lens and reforms a zonular apparatus using 15-0 suture.” “Amazing! David Chang chops a brunescent lens into 50 pieces while blindfolded with one hand tied behind his back.” In the months leading up to my first cataract surgery, I feasted on open access surgical videos, aspiring to be the next Ike Ahmed. However, after my first few cases, all I wanted to know was that my hands were just as shaky as my peers – and that my case times were just as long, and my rhexis just as oddly shaped. I kept telling myself, there’s no way Amar Agarwal ever took 40 minutes to do a routine case. It’s hard to reconcile what we see in high definition videos of surgeons doing their 8,000th case with that of a second-year resident trying desperately to insert a cannula into a paracentesis wound. We need to let novice ophthalmic surgeons know that it’s normal to struggle. Nobody is born a cataract surgeon. To that end, I am excited to share my first cataract surgery with a minute-by-minute commentary on my thought process, hopes, and fears during the case. At the time of writing, I am three months away from finishing residency. My surgeries look a lot different now than they did in the beginning. By sharing my first surgery, I hope to reassure those residents heading to the operating room for the first time that it’s ok to be shaky; it’s okay to be slow. Will I be the next Ike Ahmed? Who knows? But I’m willing to bet he looked like me right out of the gate.

CASE #1 Disclaimer: The residents at my program receive tremendous instruction from our comprehensive faculty. In these videos, whenever you see an instrument come onto the screen that is moving fluidly and with purpose, please assume that it is my intrepid attending – making my life easier and his blood pressure lower. 20 s: After collecting my thoughts, I ask for the paracentesis blade in my best impression of a confident surgeon. I grab the blade with my dominant right hand and the fixation ring in my left, followed by a quick switch that I hope my attending didn’t notice. 25 s: I make my paracentesis. It goes according to plan. I mentally congratulate myself for successfully completing three percent of a routine cataract surgery. I am then instructed to fill the anterior chamber with viscoelastic. However, it takes me several seconds to register this request as I remain transfixed by the tremendous paracentesis I have just created. 1 minute: The 2.8 mm keratome is handed to me. I am nervous about making the incision. The concept of a three-tiered incision within 800 µm of cornea seems daunting. I tunnel forward, thankful to be securely embedded in the cornea where my tremor was less noticeable. I stop at the end of my tunnel for about five seconds before deciding to enter the eye. Like a child learning to swim, my attending coaxes me a little to get me to jump in. 3 minutes: The capsulorhexis goes surprisingly well. I take my time with it, creating a flap while maintaining a healthy fear of the pupil edge. At some point, I realize I haven’t taken a breath in a while, so I use the transition from cystitome to Utrata forceps to reoxygenate my blood. Four minutes and an entire syringe of viscoelastic later, I’ve finished a (mostly) circular capsulorrhexis. 7 minutes: I call this video “The Art of Helping a Resident Insert a Phaco Handpiece Through a 2.8 mm Incision” 8 minutes: Making a groove for the first time is terrifying. Beginning residents haven’t developed the keen sense of lens depth that comes with experience. Every pass seems impossibly close to breaking through the posterior capsule. After a quick 32 passes through the nucleus resulting in what I would call the grand canyon of grooves, the nucleus is ready for disassembly. I should point out that for our first 5–10 cases our attending performs the nucleus rotation during phacoemulsification. We have to learn how to use our dominant hand before we earn the privilege of operating with both hands. 17 minutes: I remove the final nuclear fragment then take my second breath of the case. I have successfully divided and conquered a cataract. Streamers and confetti rain down from above.

What every Ike Ahmed YouTube video appears like to a newbie surgeon.

20 minutes: Irrigation/aspiration goes according to plan. I exhibit all the telltale signs of a brand new surgeon: staying too light on the pedal, afraid of extending the instrument tip beyond the iris into the equator of the capsular bag, and going slowwwwwww. 25 minutes: The lens is inserted and rotated into position. After hydration, my first clear corneal incision seals without difficulty. 31 minutes: As I pull off the drapes, I take my third – and perhaps deepest – breath of the case. One down, a career to go.

William E. Flanary II is a final year resident at the University of Iowa Department of Ophthalmology & Visual Sciences, Iowa City, IA, USA, and is Chief Medical Editor of the University of Iowa’s EyeRounds.org. He reports no conflict of interests relating to the products discussed in this article.

To view the videos online, please visit top.txp.to/issues/0717/701/

References

- DA Belyea et al., “Influence of surgery simulator training on ophthalmology resident phacoemulsification performance”, J Cataract Refract Surg, 37, 1756–1761 (2011). PMID: 21840683.