Cataracts present a massive and worsening healthcare and societal problem. Of the 39 million people today who are blind, half have lost their vision because of cataracts, with the burden disproportionately affecting developing countries (1). As the demographic bulge that is the baby boomer generation ages, things are only going to get worse. Over the next two decades, the demand for cataract surgery (already the world’s most frequently performed surgical procedure) is set to double. It has been estimated that delaying the onset of cataract formation by a decade would halve the demand for cataract surgery (2,3) – but that’s easier said than done.

Part of the problem is that, for lens fiber cells to be transparent, they have to consist almost entirely of highly ordered crystallin proteins. To achieve that, as the cells develop, they degrade their organelles, minimize extracellular space, and change the density of their cell membranes to levels approaching that of the cell’s cytoplasm – all in the name of reducing light scattering (4). This makes for fantastically transparent cells, but ones that lack the synthetic apparatus to produce new proteins. So what does this mean? Crystallin proteins, unlike others, age: they are not turned over and are some of the oldest in the body, and disruptions to the highly ordered crystallins over time leads to crystallin aggregation, opacity… and cataract.

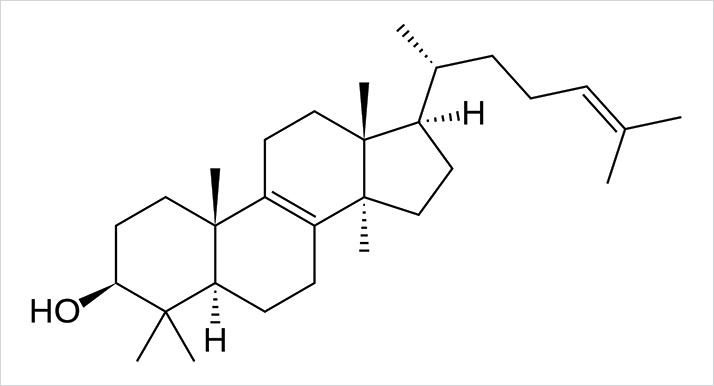

Kang Zhang is both a physician and a genetics researcher, so when two young children with cataracts walked into his clinic, he was able to do something most physicians couldn’t – sequence their genomes (5). When he did, he found mutations in the gene that encodes lanosterol synthase (LSS). Since little was known about the role of lanosterol (Figure 1) in the eye, he and his team performed tissue culture experiments in a number of cell lines that expressed “six known cataract-causing mutant crystallin proteins” – which resulted in collections of misfolded proteins called aggresomes. The application of lanosterol (or the co-expression of wild-type LSS) went a long way to dissolving the protein aggregates and rescuing the phenotype. Further, isolated cataractous rabbit lenses significantly increased in clarity following incubation with lanosterol over a six-day period. But cell culture and in vitro experiments are one thing; activity in vivo is another, so the team decided to see if they could use lanosterol to treat dogs with age-related cataract. An initial 100 µg dose of a nanoparticle formulation of lanosterol was injected into the vitreous cavity, followed by the administration of one 50 µl drop of lanosterol every three days over a six-week period. All seven lanosterol-treated dogs exhibited decreased cataract density relative to both baseline levels and the vehicle-only treated fellow eyes.

So how long will we have to wait until patients’ cataracts are cured with eyedrops? Zhang thinks not very long, telling Nature that, “since lanosterol is a molecule produced by our own body, the toxicity issue of such a drug is minimal,” and that, “I think we will go forward to commencing a clinical trial in humans within the next year” (6).

References

- World Health Organization, “Priority eye diseases: Cataract”, (2015). Available at: http:// bit.ly/1rTbp2S. Accessed July 27, 2015. A Taylor, “Cataract: relationship between nutrition and oxidation”, J Am Coll Nutr, 12, 138–146 (1993). PMID: 8463513. B Garry, T Hugh, “Cataract blindness: challenges for the 21st century”, Bull World Health Organ, 79, 249–256 (2001). PMID: 11285671. JF Hejtmancik, “Ophthalmology: Cataracts dissolved.” Nature, 523, 540–541 (2015). PMID: 26200338. L Zhao, et al., “Lanosterol reverses protein aggregation in cataracts”, Nature, 523, 606–611 (2015). PMID: 26200341. G Marsh, “Vision: Eye drops shrink cataracts in dogs (N&V)”, Nature (2015). Available online at bit.ly/naturecataracts.