In the quest to move away from topical management of glaucoma – and the associated issues, including non-compliance – the field has seen a shift towards surgical management, with a boom in minimally invasive technologies transforming glaucoma care. One such option is cyclophotocoagulation – a procedure which targets the ciliary body epithelium to modulate aqueous production and lower IOP. Here, two surgeons share their preferred cyclophotocoagulation approaches, and talk through how – and why – they perform them.

- Many surgical approaches focus on reducing IOP by improving outflow

- Cyclophotocoagulation reduces inflow – and thus IOP – by decreasing aqueous production

- Endoscopic cyclophotocoagulation (ECP) directly targets the ciliary processes for treatment via an ab interno approach

- Gain top tips from my own experiences, and learn how ECP has benefited my patients.

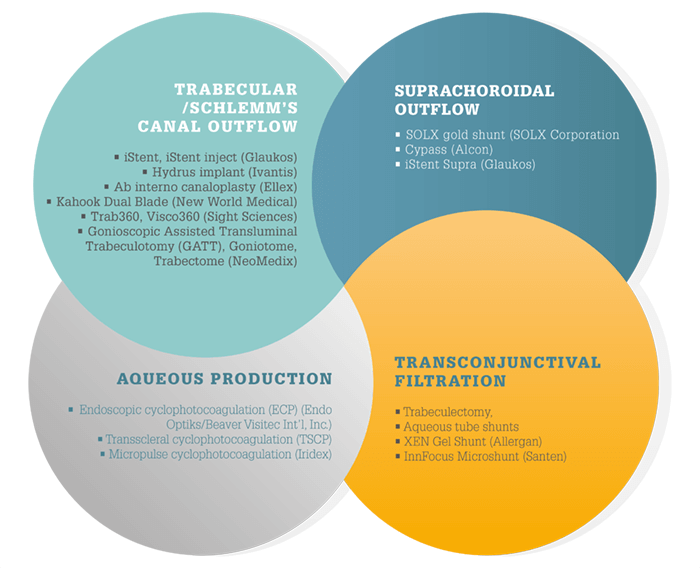

Glaucoma is epidemic worldwide – and the number of people affected is set to increase to 79.6 million by 2020 – 74 percent of which will have open angle glaucoma (OAG) (1). Although a multifactorial disease, the primary treatment approach is IOP reduction to prevent further damage to the optic nerve. First-line therapy with topical hypotensive medications is effective when used according to direction; however, these can be limited by poor compliance or insufficient efficacy. It’s why multiple surgical IOP-lowering treatment options are also available and in development, each of which targets different outflow and filtration pathways (see Surgical management of IOP). Of these, treatments that target aqueous production are gaining in popularity.

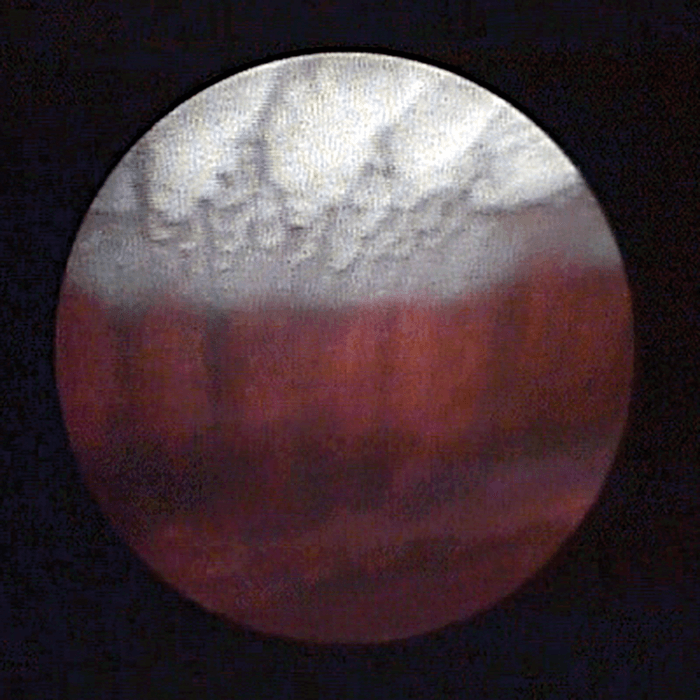

It was first discovered in 1905 that severing the ciliary body could decrease IOP (2). In the 1960s, transscleral ultrasound radiation was used to achieve the necessary destruction (3). Since then, multiple methods of cyclodestruction have been popularized, including cyclophotocoagulation through a transpupillary route, or a contact or non-contact transscleral route (4). Transscleral cyclophotocoagulation (TSCP) – in which ciliary processes are targeted from an external approach with a Nd:YAG or diode laser – has been through several iterations since it was first introduced in the 1970s. In 1992, Martin Uram introduced the use of an intraocular endoscope paired with a diode laser to achieve cyclophotocoagulation using an ab interno approach (5). Endoscopic cyclophotocoagulation (ECP) applies 810 nm wavelength light directly onto the ciliary processes, with positioning visualized by the surgeon through the endoscope. Here, I overview my top tips for performing ECP, and share some case studies of its use.

ECP: Top Tips

Anterior segment approach- The key to this approach is to treat as many ciliary processes as possible. Even with a 360 degree treatment, the posterior aspect of the processes can be missed. For a significant effect it is advisable to treat 360 degrees, including in between each process. Many surgeons do not treat the intervening space between each process, but as the ciliary epithelium completely encompasses each process – including between the peaks and valleys – it is advisable.

- Titrate the power to achieve a good effect with whitening and shrinking of each process, taking care not to over-treat and cause them to ‘pop’. Laser power can be adjusted manually and length of delivery controlled by the foot pedal. Proximity of the probe to the process being treated is important as being too close can result in delivering too much energy – I have found that it is ideal to have six to 10 processes within view.

- Thoroughly inflate the ciliary sulcus with a heavy viscoelastic until the iris nearly touches the cornea. Healon GV (Johnson&Johnson Vision) is my choice, because there is no bubble formation, the higher molecular weight maintains the space, and I find it easier to remove than others. Pushing the iris forward and the lens back will give you the space in which to work.

- A 2.2 mm limbal clear corneal incision works well. Too large an incision may cause the loss of viscoelastic, resulting in poor inflation. When complete, ensure the removal of all the viscoelastic. I have found that some form of irrigation and aspiration is typically needed to avoid pressure spikes. Flushing with BSS and trying to ‘burp’ it out may not be sufficient.

- For the anterior approach, I prefer the patient to be pseudophakic. It is possible to treat a phakic eye, but it is much more difficult. If the patient is aphakic and vitrectomized, do not try to inflate the sulcus with viscoelastic – use an anterior chamber maintainer, which will preserve the integrity of the globe while the surgery is performed.

- Execute a pars plana incision, generally with a 20 or 19 G MVR blade or a 2.2 mm keratome. Perform the procedure through a standard three port vitrectomy or a two port vitrectomy with an anterior chamber maintainer. Place the vitrector in one port and the endoscope in the other. View with the endoscope and perform a limited vitrectomy. Then perform the ECP procedure. Once accomplished, switch hands and perform a vitrectomy and ECP with the other hand from the opposite side. I find this technique works quite well even for anterior segment surgeons.

- For the pars plana approach, it is advisable to avoid 360 degree treatments – a greater portion of the ciliary epithelium is treated due to improved access to the entire length of the ciliary processes. This is especially true with ECP Plus (see below), which includes not only the pars plana approach but treatment of all of the ciliary processes along with approximately 1–2 mm of pars plana. This treatment may result in acute IOP reductions and should be used with care to avoid hypotony.

- To facilitate treatment of the ciliary processes via the anterior or posterior approach, scleral depression may be used. This maneuver splays out the processes, allowing for more complete treatment of the processes and the areas in between. If ECP becomes challenging due to significant anterior segment pathology, such as posterior synechiae, consider the pars plana approach.

- Anterior and posterior synechiae can typically be severed to facilitate access to the ciliary sulcus. In some cases, residual lens material or posterior iris synechiae are discovered. Removal is possible if necessary, however, these can sometimes be circumvented by manipulation of the probe. This will require an adjustment of the power as the probe tip will generally be in close proximity to the ciliary processes. As previously stated, if these are severe consider a pars plana approach.

- The most common complication of ECP is inflammation, and this needs to be managed thoroughly. Treatments can include intracameral dexamethasone (600–1,000 µg), subconjunctival dexamethasone, and IV or topical steroids. Oral prednisone can also be administered postoperatively. I find it best to treat aggressively at first, and then taper relatively quickly to avoid extended treatment. As steroid response can occasionally mask IOP lowering, taper the steroid once inflammation is controlled and reevaluate the IOP if the desired IOP has not been reached.

ECP: case by case

Many other surgical options are only available to patients with OAG, but ECP can be used in a wide spectrum of glaucoma patients – either OAG or chronic angle-closure – as well as at any disease stage. For patients with refractory glaucoma who have failed other procedures, the ECP Plus procedure (ECP via a pars plana approach combined with vitrectomy and pars plana laser treatment) has been shown to be effective (6). ECP can also be effectively combined with any other outflow surgery, and because techniques can be readily learned by anterior segment surgeons, it can be used in combination with cataract surgery. The flexibility of ECP in the glaucoma treatment paradigm is illustrated in the following three cases.Case 1

A 68-year old Asian female with a history of mixed mechanism glaucoma and chronic angle closure presented with moderate glaucoma damage. Her cup-to-disc ratio was 0.75, and her pressures were controlled at 16 –18 mmHg with two medications (latanoprost at night and timolol in the morning). Her visual field tests were stable with a mean deviation of approximately -6.0 dB. The patient manifested visually significant cataracts (best corrected visual acuity, 20/60). After discussion with the patient, we decided to combine cataract surgery with ECP; because of the patient’s angle closure, we determined that reducing aqueous production was a better option than angle-based outflow procedures. Following combined cataract surgery with ECP, she initially maintained her glaucoma medications. We then tapered off her medication, and her IOP now sits between 15–17 mmHg without any medications. Her visual field tests are stable and her visual acuity has improved to 20/20.Case 2

A 32-year old Caucasian female presented with symptoms of intermittent angle closure, including headaches, eye pain, and visual phenomenon – particularly at night time. Gonioscopy and anterior segment OCT revealed that she had appositional angle closure in three to four quadrants. The patient was also hyperopic with a +2.25 D correction. The first treatment, a laser iridotomy, was successful at creating a patent opening, but the patient was still experiencing symptoms of intermittent angle closure. Repeat gonioscopy verified that the angles were still quite narrow, and the patient had a plateau-type approach, some phacomorphic component, and that the peripheral iris was also very anteriorly displaced. Ultrasound biomicroscopy (UBM) verified the very narrow angles and also revealed some anterior lens vault. Very prominent, anteriorly rotated ciliary processes were pushing the peripheral iris anteriorly. Pilocarpine treatment was tried, but the patient had severe side effects including decreased vision. Repeat laser iridoplasty was an option as it was somewhat effective previously, but the patient considered this to be a “band-aid” measure that would not last, so we discussed incisional surgery. Even though her vision was 20/25 with a clear lens, we opted for lens extraction combined with endoscopic cycloplasty (ECPL) to improve her anatomical abnormality. The ciliary processes were treated with laser to shrink and flatten them and pull them more posteriorly, thereby deepening the angle and decreasing the amount of contact between the ciliary processes and the posterior iris. The treatment covered 270-300 degrees and was performed through the cataract incision. The patient is happy with her visual acuity of 20/20, and her pressure, optic nerve exams and visual field tests are stable. Most importantly, she has had total relief of her angle closure symptoms for three years.Case 3

This final case is a 72-year old Latino male with advanced primary open angle glaucoma (POAG). His cup-to-disc ratio was 0.90 in one eye and 0.95 in the other, with IOP at 16 –18 mmHg. Both eyes had previous trabeculectomies and Baerveldt aqueous tube shunt implants. Both of these surgeries failed to adequately control IOP, and the patient was receiving maximum topical medication to maintain his target pressure of below 15 mmHg. The patient was lost to follow-up for one year and when he returned, he was also taking oral acetazolamide 500 mg twice daily because the drops alone were not controlling his IOP. He was uncomfortable taking the acetazolamide and experiencing side effects, including tingling, fatigue and gastrointestinal symptoms, prompting him to return to me for a new option. At this point, his central vision was still 20/25 but he had severe visual field constriction. Talking through the options, we decided to perform ECP on each eye at separate sessions. Each received 360 degrees of ECP from an anterior approach. Two years following treatment his IOP is maintained at 12 mmHg, and though he is still on maximum topical therapy, he is no longer taking acetazolamide. Brian Francis is the holder of the Rupert and Gertrude Stieger Chair in Vision Research, and Professor of Ophthalmology at the Doheny Eye Institute and Stein Eye Institute, David Geffen School of Medicine, University of California Los Angeles. Francis reports that he is a consultant for Endo Optiks/Beaver-Visitec, Inc.References

- HA Quigley and AT Broman. “The number of people with glaucoma worldwide in 2010 and 2020”, Br J Ophthalmol, 90, 262–267 (2006). PMID: 16488940. L Heine. “Die Cyklodialyse, eine neue glaucomoperation”, Deutsche Med Wochenschr, 31, 824–825 (1905). EW Purnell et al., “Focal chorioretinitis produced by ultrasound”, Invest Ophthalmol, 3, 657–664 (1964). PMID: 14238877. SA Pastor et al., “Cyclophotocoagulation: a report by the American Academy of Ophthalmology”, Ophthalmology, 108, 2130–2138 (2001). PMID: 11713091. M Uram. “Ophthalmic laser microendoscope ciliary process ablation in the management of neovascular glaucoma”, Ophthalmology, 99, 1823–1828 (1992). PMID: 1480398. JC Tan et al., “Endoscopic cyclophotocoagulation and pars plana ablation (ECP-plus) to treat refractory glaucoma”, J Glaucoma, 25, e117–122 (2016). PMID: 26020690.