- Rubbing your eyes is bad.

- Some say eye rubbing is the cause of keratoconus, others say it just reveals and exacerbates it.

- There is total consensus on one matter: eye rubbing is bad – and our patients need to know.

- The “Don’t Rub Your Eyes” message needs to become part of our cultural heritage – like carrots being good for night vision. Spread the word!

What corneal and refractive surgeons can do is incredible. I can imagine going back in time and telling my father who was a pioneer in refractive surgery in Brazil but passed away prematurely in 1994, what we can routinely do and achieve today – safely, with reproducibly great outcomes – thanks to the corneal imaging and advanced laser technologies that we have at our disposal. Would a surgeon from the 1980s believe you if you told them that you could help patients with corneal ectasias by selectively ablating the cornea with a laser? Or that we could halt corneal ectasias with UV light and vitamin B2? And yet, that’s what we’re able to do today. But we have to be clear about what we’re doing for these patients, and why. Treating diseased corneas is a whole different world from enabling patients to throw away their spectacles and contact lenses. While there are no guarantees or risk-free procedures in Medicine, I wrote an editorial in the Brazilian Journal of Ophthalmology (RBO) back in 2013 (1), stating that we must educate our patients and highlight the fundamental differences between elective (non-aesthetic) treatments with a refractive purpose, and those for the visual rehabilitation of patients with corneal disease. For the latter, the education of patients and their families is fundamental to the success of your intervention, as it enables patients to manage their disease better, and it also helps them maintain realistic expectations of what treatment can achieve. We created a website in Portuguese for this very purpose: www.tudosobreceratocone.com.br.

But there’s an equally important message: one that can have a major impact in reducing keratoconus-related vision loss, and one that receives relatively little exposure. It is about educating patients about the grave risk to their cornea of an almost unconscious action: rubbing their eyes. The first person credited with an accurate description of keratoconus is the British physician, John Nottingham, who in 1854, published his landmark treatise “Practical Observations on Conical Cornea and on the Short Sight and Other Defects of Vision Connected With It” (Figure 1). The increased curvature, thinning (and possible loss of corneal transparency) described by Nottingham are now known to be manifestations of a weakening cornea, and we also know that there are both genetic and environmental factors that can lead to keratoconus developing (2).

International accord

The Global Delphi Panel of Keratoconus and Ectatic Diseases met in 2014 (3) to produce a consensus statement on the definition, concepts, clinical management and surgical treatments of these diseases. There was a great deal of vigorous debate over the causes of corneal ectasias like keratoconus (believe me, I was there!) but we unanimously agreed that the habit of eye rubbing aggravates the disease, increasing the chance (or rate) of progression – with a consequent worsening of vision. Further, it was agreed that the continuous trauma to the cornea that’s related to this habit may even cause biomechanical decompensation and ectasia evolution in patients without the primary disease! Advances in corneal imaging are enabling corneal specialists to begin documenting the fact – but let me be clear: there is no doubt that eye rubbing is bad and should be avoided. There was one other important take-away from the Global Delphi Panel: we all agreed that rigid gas permeable (RGP) contact lenses – which improve patients’ vision greatly – unfortunately do not bring the benefit of stabilizing the disease. In fact, it was agreed that lenses, when poorly adapted to the patient’s cornea, may even aggravate ectasia and therefore RGP lenses absolutely need to be well adapted to each patient – and this includes appropriate and adequate patient guidance (3). The literature on keratoconus is increasing exponentially, and there are already over one hundred articles that point to the relationship between eye rubbing and corneal ectatic disorders. Damien Gatinel asked a fundamental question in his editorial, “Eye rubbing: a sine qua non for keratoconus?” (4). Though the statement ‘sine qua non’ – something that is absolutely essential – may be an exaggeration, we prefer to maintain the two-hit hypothesis (an underlying genetic predisposition coupled with external environmental factors, including eye rubbing and atopy) described by McGhee (5). In fact, the severity of keratoconus was already related to the dominant hand (6)(7)(8)(9), and rubbing by the hand is also thought to be a possible cause of unilateral disease (10)(11)(12). Such a consideration of unilateral ectasia should not contrast with the consensus that keratoconus is an asymmetric but also bilateral disease. In fact, it was also agreed that ectasia secondary to mechanical causes can occur unilaterally and in any cornea (3).

An educational avenue

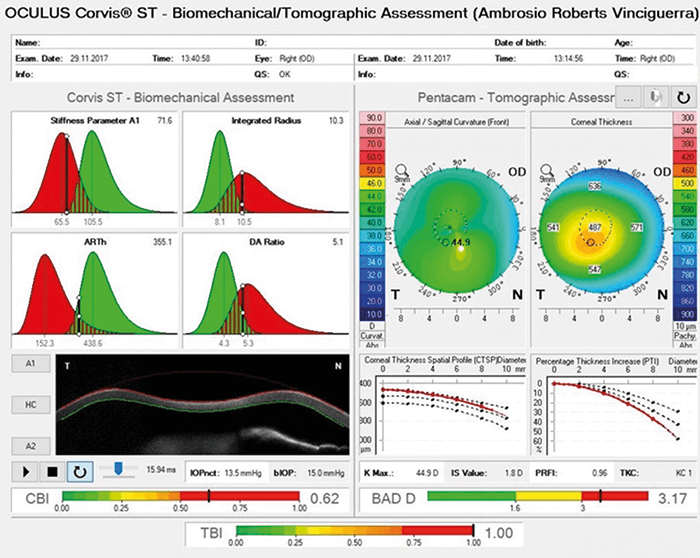

Much work has been devoted to screening for corneas that are susceptible to corneal ectasias (particularly those subclinical or forme fruste cases), with approaches like corneal topography, tomography, pachymetry and tonometry with biomechanical assessment (Figure 2). The resulting evidence has led us to believe that corneal ectasia occurs thanks to a failure in the biomechanical resistance of the cornea, and this is related to two primary factors: the structure of the cornea, and the trauma of the environment (13)(14). We can do a lot to help patients with keratoconus. Interventions such as corneal cross-linking (CXL) can help arrest disease progression, though there’s plenty more debate on when to perform CXL – perhaps before ectatic progression is documented (5)(15)(16). Procedures like PRK, intracorneal ring segments, RGP contact lenses and even phakic IOLs can help with the refractive consequences of a thinning (and increasingly cone-shaped) cornea (17). And if all else fails, there’s always keratoplasty, including the benefits of deep anterior lamellar keratoplasty or DALK (18). But the simplest – and perhaps the most effective – option could be to hammer a simple message into the mindset of the public: don’t rub your eyes. If the message could become as popular as “fish is food for the brain” and “carrots help you see better at night,” it would really make a difference. Beyond basic education, there are other ways we could make a difference; an “eyerubberometer” for example – a simple wearable device that could detect the characteristic motion of eye rubbing and alert the wearer that they’re risking their eyesight. Admittedly, people tend to rub their eyes if they have an ocular allergy or ocular surface disease – both of which are treatable, so it’s not all about raising awareness. But we have a duty to advise patients about the terrible consequences of what appears to be a fairly benign habit. After all, eye rubbing can cause and aggravate keratoconus – and it can even cause problems in the retina and aggravate glaucoma. “Don’t Rub Your Eyes!” It’s a simple message – one that may require a long-lasting campaign, I admit – but it will prevent vision loss. Please help spread the word! Renato Ambrósio Jr. Director of Cornea and Refractive Surgery, Instituto de Olhos Renato Ambrósio, Rio de Janeiro, and Adjunct Professor of Ophthalmology of the Federal University of the State of Rio de Janeiro (UniRIO) and Affiliated Professor of the Federal University of São Paulo (UNIFESP).References

- R Ambrósio Jr., Revista Brasileira de Oftalmologia, 72, 85–86 (2013). A Gokul, DV Patel, CN McGhee, Cornea, 35, 673–678 (2016). PMID: 26989959. JA Gomes et al., Cornea, 34, 359–369 (2015). PMID: 25738235. D. Gatinel, Int J Kerat Ect Cor Dis, 5, 6–12 (2016). Available at: bit.ly/gatinel. CN McGhee et al., Cornea, 34, S16–23 (2015). PMID: 26114829. CW McMonnies, GC Boneham, Clin Exp Optom, 86, 376–384 (2003). PMID: 14632614. B Jafri, H Lichter, RD Stulting, Cornea, 23, 560–564 (2004). PMID: 15256993. K Zadnik et al., Cornea, 21, 671–679 (2002). PMID: 12352084. JG Krachmer, RS Feder, MW Belin, Surv Ophthalmol, 28, 293–322 (1984). PMID: 6230745. AJ Phillips, Clin Exp Optom, 86, 399–402 (2003). PMID: 14632617. JH Krachmer, Cornea, 23, 539–540 (2004). PMID: 15256988. AS Ioannidis, L Speedwell, KK Nischal, Am J Ophthalmol, 139, 356–357 (2005). PMID: 15734005. R Ambrósio Jr. et al., J Cataract Refract Surg, 41, 1335–1336 (2015). PMID: 27079610. R Ambrósio Jr. et al., J Refract Surg, 33, 434–443 (2017). PMID: 28681902. KA Knutsson et al., Br J Ophthalmol (2017). PMID: 28655729. AC da Paz et al., J Ophthalmol, 890823 (2014). PMID: 25215226. F Faria-Correia, A Luz, R Ambrósio Jr., “Managing corneal ectasia prior to keratoplasty”, Expert Rev. Ophthalmol, 33–48 (2015). H Liu et al., “Efficacy and safety of deep anterior lamellar keratoplasty vs. penetrating keratoplasty for keratoconus: a meta-analysis”, PLoS One, 10, e0113332 (2015). PMID: 25633311