Managing glaucoma has changed tremendously over the past 20 years! I can see this change very clearly when I compare today’s available options with the time I started my work in glaucoma, when I only had medications, canaloplasty, trabeculectomy, and some tube shunts to offer to patients. Since then, the introduction of MIGS procedures has consistently improved glaucoma patients’ outcomes, and the evolution of MIGS has given glaucoma surgeons many new tools in their armamentarium. The development of new devices – and new surgical techniques and procedures – continues apace, often overloading surgeons with choice. It almost seems like manufacturers are releasing new MIGS devices and improvements every fortnight – so do we really require any more MIGS options?

Trabecular or conventional pathway

The traditionally used trabecular outflow pathway as a target to lower IOP has both benefits and disadvantages. Firstly, it is a physiological approach that requires no bleb management, and it is the source of 75 percent of outflow resistance. On the other hand, targeting the conventional outflow pathway has no effect on resistance distal to collector channel entrances, and IOP lowering is limited due to the episcleral venous pressure and distal outflow capacity floor effect (1).

Our understanding of outflow resistance shows it to be a combination of three factors: loss of permeability of the trabecular meshwork, collapse of Schlemm’s Canal, and closing of the collector channel entrances. The difficulties with the conventional, trabecular pathway include the fact that Schlemm’s canal isn’t a simple tube, but it has a more complex cylindrical structure, making targeting and circumnavigating the canal more challenging (2).

Subconjunctival filtration

Let’s move on to the subconjunctival filtration pathway, which also boasts some advantages and disadvantages. It doesn’t compromise physiological outflow as it creates a new artificial pathway for drainage via a bleb, thus preserving remaining physiological filtration. Filtering procedures are also not negatively impacted by the limitation of episcleral venous pressure floors and are independent of the suprachoroidal pressure gradient. Thus, these procedures have the most potent outflow potential, resulting in IOP lowering to less than 10 mmHg. Nevertheless, due to the risk of fibrosis and despite the use of anti-metabolites during the procedure, there is a great variability in the IOP lowering effect, and bleb management is still often necessary, requiring close patient management. Patients may have a predisposition to fibrosis due to previous therapy with prostaglandin analogues or preservatives from drops, or due to the nature of the surgical procedure itself. Subconjunctival flow constitutes persistent mechanical stress, with aqueous humor present in the subconjunctival space (1).

Uveoscleral outflow – suprachoroidal space

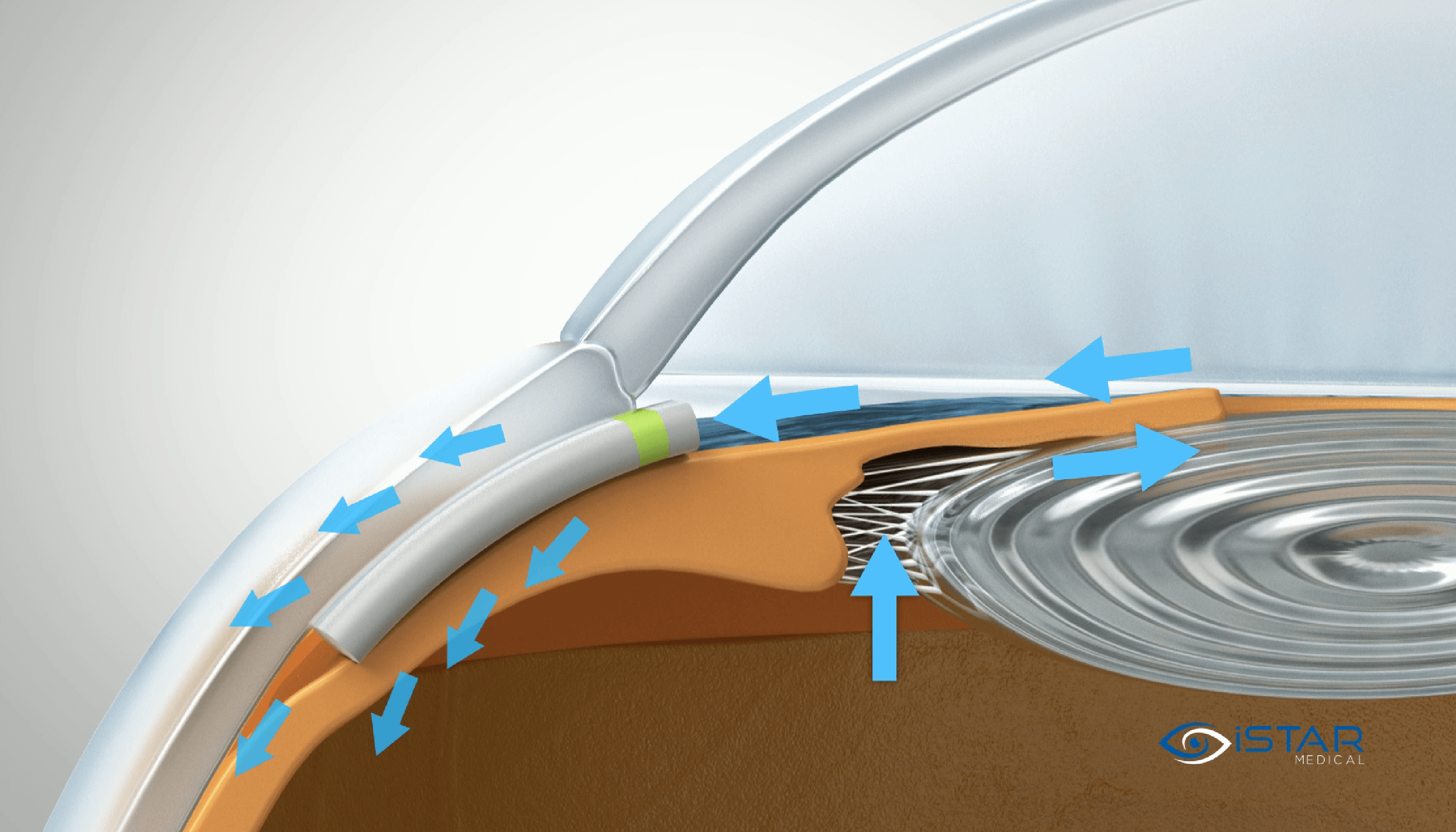

In 1905, Leopold Heine published an article on the strong IOP-lowering power of his ab externo cyclodialysis procedure, which created a drainage corridor between the anterior chamber and the supraciliary space (3). Over the years, there has been a lot of interest in this pathway as it has multiple benefits, including the fact that no bleb management is required – the outflow is physiological. There is also the potential for greater IOP lowering compared with the conventional outflow, as the aqueous absorption is rapid into the suprachoroidal space, and there is no risk of distal resistance or a floor effect that could limit the extent of IOP reduction. Up to 50 percent of aqueous drainage in normal, younger eyes is via the uveoscleral pathway (4, 5, 6). So why has this method of lowering IOP not been more commonly used? There is a risk of choroidal detachment or iris cleft, and the exact risk of fibrosis is still unclear, making the long-term effectiveness of devices targeting this pathway uncertain (1).

There is no epithelial barrier in the angle between the anterior chamber and the ciliary muscle, but as eyes age, muscle fibres are lost, and there is an increase in extracellular fibrillar material. That means that the uveoscleral outflow is much lower in older patients (7). This is why improving this pathway can give great pressure reductions – a great space and function for a new MIGS device.

Emi and colleagues (8) showed the stable pressure gradient between the anterior chamber and the suprachoroidal (pressure difference of around 4 mm) and supraciliary (pressure difference of around 1 mm) space, enabling a continuous outflow into the suprachoroidal space with effective IOP lowering, and with a proportionally greater degree of lowering at higher levels of IOP. The area of resorption within the suprachoroidal space is 160 times larger than in the trabecular meshwork, with a single entry opening the full space giving greater potential for IOP lowering. This is also evident in the therapeutical approach of prostaglandins, which lower IOP more effectively than any other topical drug, with their mechanism of action improving the uveoscleral outflow (9).

Enter the MINIject

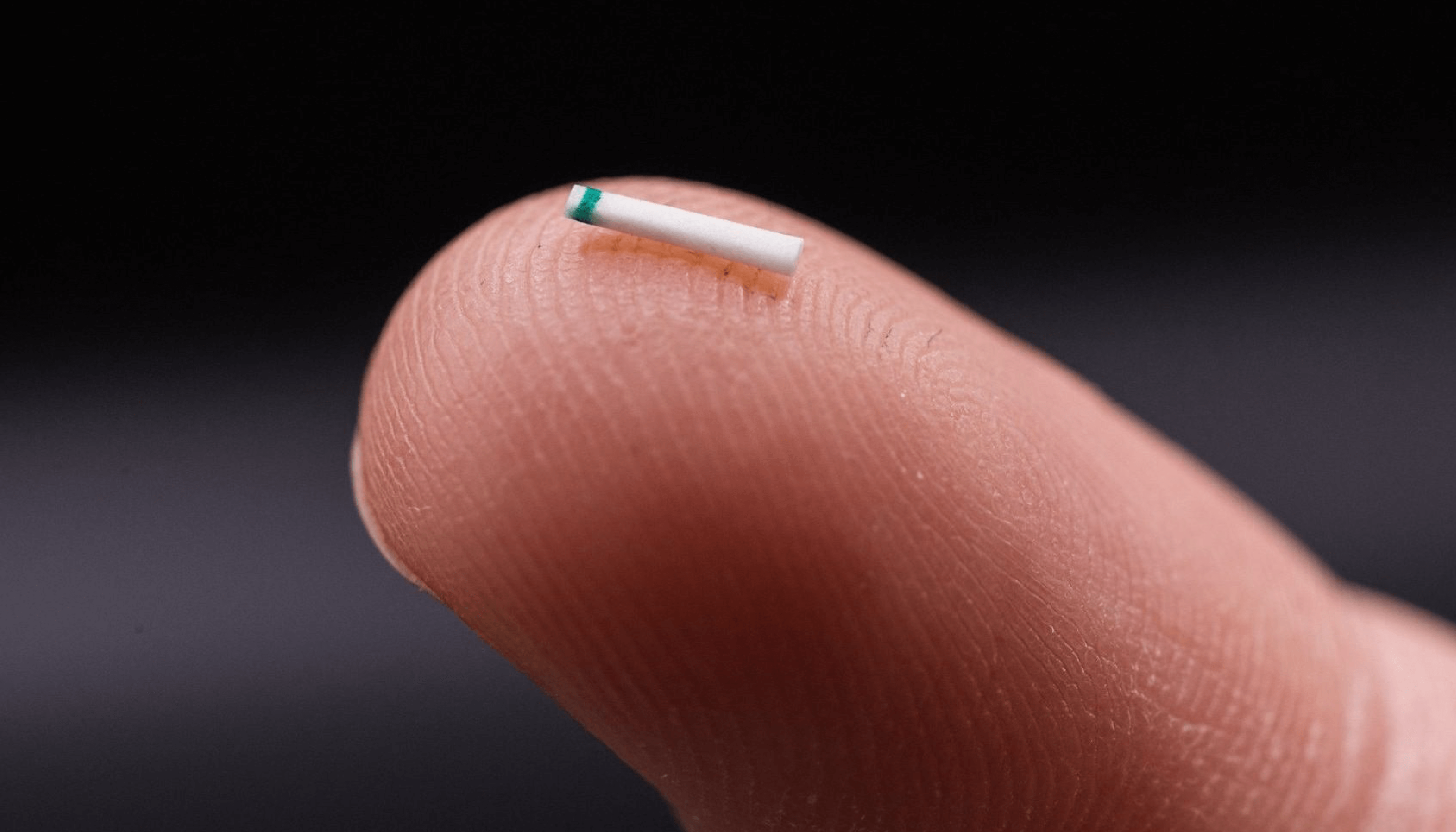

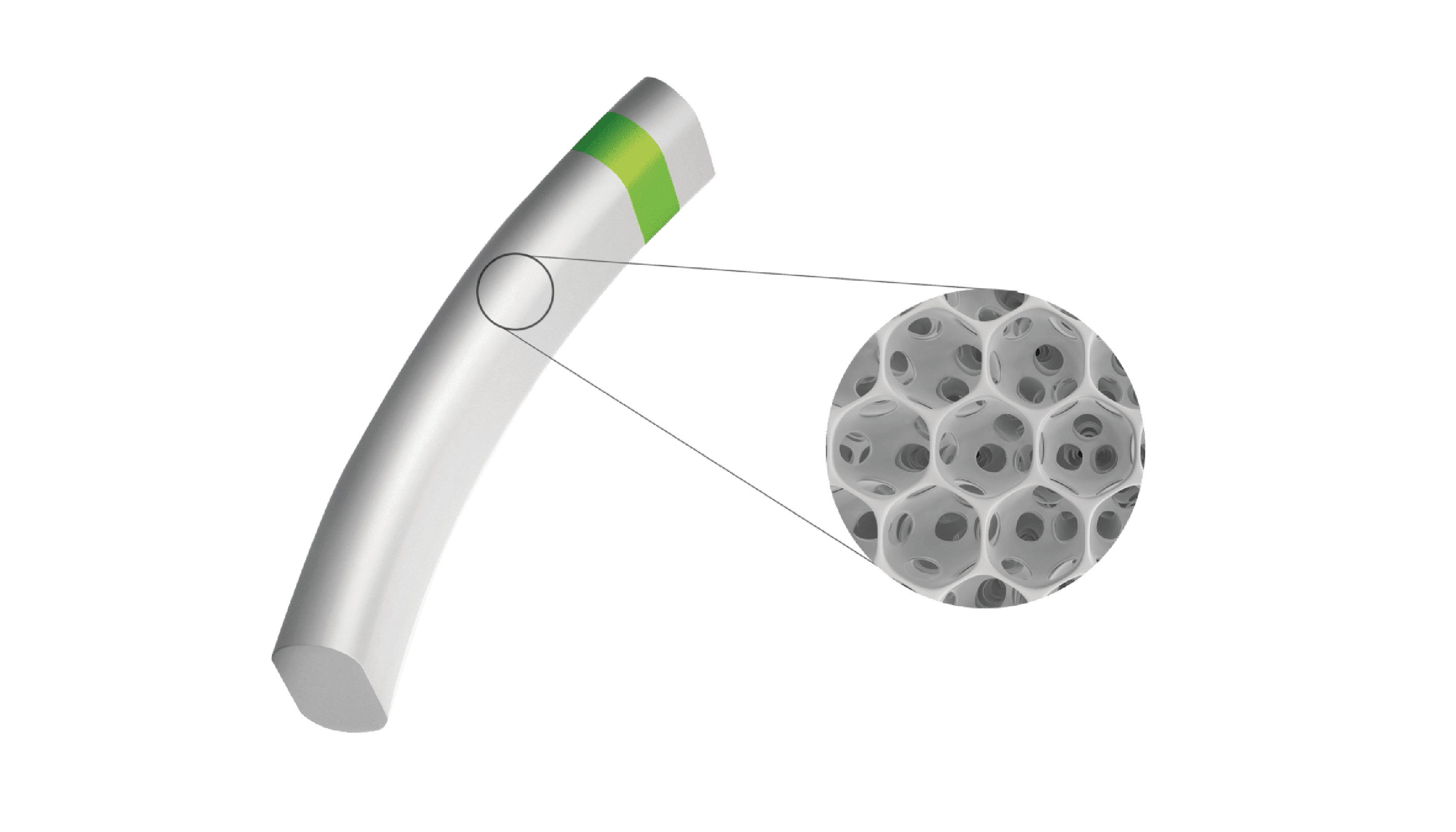

This is where the MINIject® device can truly make a difference. MINIject is iSTAR Medical’s innovative MIGS device for patients with open-angle glaucoma. It is currently the only commercially available MIGS device targeting the supraciliary space, which has been shown to deliver safe, meaningful, and sustained control of intraocular pressure. In contrast to the previously available CyPass Micro-stent (Alcon), which was implanted in the same region, MINIject is different thanks to its innovative and proprietary STAR® material that the device is made of – which minimizes scarring, fibrosis and encapsulation, and thus sustains the efficacy of the implant over time (10, 11).

So, do we need more MIGS?

As glaucoma surgeons, we need a long-lasting MIGS option that offers a great balance of efficacy and safety: with a better safety profile than subconjunctival devices where a bleb is necessary, yet also more effective than trabecular meshwork-based MIGS options. MINIject’s favourable safety profile and meaningful efficacy already looks promising up to two years, thanks to the power of the uveoscleral outflow pathway accessed via an ab interno route, as well as the novel STAR material used (11).

So finally – what is my answer to the question opening this article? Yes, we really do need this new MIGS solution using the suprachoroidal approach! I, for one, will continue to implant MINIject and follow its long-term results in my patients, and I encourage my colleagues to do the same.

This article summarises the views of Karsten Klabe from a lecture independently prepared by him and delivered during the iSTAR Medical symposium at the 2022 EGS Congress.

References

- K Gillman, K Mansouri, “Minimally invasive glaucoma surgery: Where is the evidence?” Asia Pc J Ophthalmol, 9, 203 (2020). PMID: 32501895.

- NH Andrew et al., “A review of aqueous outflow resistance and its relevance to microinvasive glaucoma surgery,” Surv Ophthalmol, 65, 18 (2020). PMID: 31425701.

- L Heine, “Die Cyclodialyse, eine neue glaukomoperation,” Dtsch Med Wschr, 824 (1905).

- CB Toris et al., “Aqueous humor dynamic in the aging human eye,” Am J Ophthalmol, 127, 407 (1999). PMID: 10218693.

- A Gigon, T Shaarawy, “The suprachoroidal route in glaucoma surgery,” J Curr Glaucoma Pract, 10, 13 (2016). PMID: 27231415.

- A Bill, CI Phillips, “Uveoscleral drainage of aqueous humour in human eyes,” Exp Eye Res, 12, 275 (1971). PMID: 5130270.

- A Alm, SFE Nilsson, “Uveoscleral outflow – a review,” Exp Eye Res, 88, 760 (2009). PMID: 19150349.

- K Emi et al., “Hydrostatic pressure of the suprachoroidal space,” Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci, 30, 233 (1989). PMID: 2914753.

- RN Weinreb et al., “Effects of prostaglandins on the aqueous humor outflow pathways,” Surv Ophthalmol, 47, S53 (2002). PMID: 12204701.

- I Grierson et al., “A novel suprachoroidal microinvasive glaucoma implant: in vivo biocompatibility and biointegration,” BMC Biomed Eng 2, 10 (2020). 33073174.

- P Denis et al., “Two-year outcomes of the MINIject drainage system for uncontrolled glaucoma from the STAR-I first-in-human trial,” Br J Ophthalmology, 106, 65 (2022). PMID: 33011690.