“‘Demodex – that old story,’ groaned an old colleague of mine,” recalled Teifi James: “The debate around their role in lid inflammation has being going on for a very long time.” There are many reasons why this debate has gone back and forth over the years, the main ones being we just don’t fully understand the relationship between this mite and their human host – some people who harbor the mite are totally asymptomatic, whereas others suffer terrible problems. So what exactly do we know about the role Demodex plays in disorders like blepharitis and should the eyecare community be paying more attention to it? Much like blepharitis, Demodex can come in anterior and posterior versions – D. folliculorum inhabits (unsurprisingly, given its name) the eyelash follicles, and D. brevis lives in the meibomian glands. In the vast majority of cases, the mites go unobserved and cause no untoward symptoms. But in some cases – usually related to co-morbidities like ocular rosacea and alterations of the immune system – mite populations increase dramatically (1), and that’s often when the problems start. Jesús Merayo explains: “Our focus isn’t on whether Demodex are present, but whether there is overgrowth.” For example, one study (2) identified 0.69 mites per lash in patients with blepharitis, compared with 0.08 mites per lash in those without (p=0.006). Jesús Merayo remarks that “Demodex alone is probably not guilty – but their overgrowth probably is.” Serge Doan explains the diagnostic dilemma: “Finding one or two Demodex in one patient doesn’t imply infestation – but what is the threshold for defining an overgrowth of Demodex? It seems that a reasonable threshold could be more than five Demodex for 10 eyelashes, or more than three Demodex on one eyelash.”

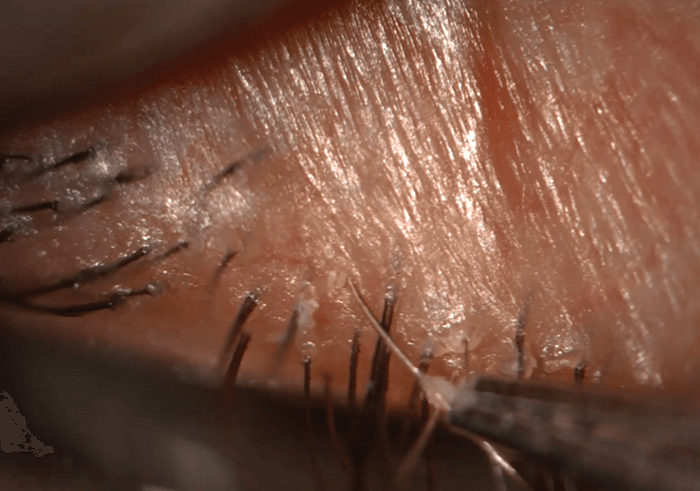

Figure 1. Using a 40 × objective on a slit lamp, Demodex tails can be observed protruding from the lash follicles once cylindrical dandruff is removed. Credit: Teifi James.

Demodex: doing more harm than good

It is clear that the presence of Demodex can make blepharitis worse. For example, severe itching is a commonly-reported symptom reported by patients with blepharitis, but it’s significantly (p<0.001) more common when Demodex are present than when they’re absent (3). However, the Demodex “rap sheet” doesn’t stop at blepharitis; it’s also associated with a number of other eyelid disorders such as chalazia and rosacea (4, 5), and multiple ocular manifestations have been identified too, including superficial corneal neovascularization, marginal corneal infiltration, superficial corneal opacity and corneal scarring (6). Precisely why Demodex associates with these conditions is unclear, but the likely culprit is that they cause inflammation. Although it’s possible that the mites themselves cause mechanical irritation of sebaceous glands and hair follicles (and may even block them), it’s thought that Demodex can cause rosacea by introducing bacteria like Bacillus olerionius into sebaceous glands and hair follicles, which then initiate host immune responses and inflammation (5). Serge Doan believes that “The bacteria are probably the key, because we know that rosacea is treated with topical or systemic antibiotics such as doxycycline, which we know have no effect on Demodex.” On the other hand, Serge Doan notes that “When we analyze the meibomian secretions of patients with blepharitis and rosacea, we see modified meibum and fatty acids. We know the mites feed on this, so perhaps another element here is: are Demodex present in these cases precisely because it has something to eat?”- How Demodex interact with their human host

- Who is most affected by Demodex, and why?

- What the pathological consequences of Demodex infestation are, and how this leads to blepharitis and other mite-related conditions

- What the threshold is that defines “Demodex overgrowth?”

- What are the most effective ways to easily diagnose infestation and related conditions?

Identifying and managing Demodex

Whether it’s through cause or effect, it’s likely that Demodex are present if you see cylindrical dandruff the base of patients eyelashes (7). The presence of these mites has traditionally been established through microscopic examination of epilated lashes. But you don’t have to pluck your patients’ eyelashes; they can be examined in situ by rotating the lashes within the follicle (8), using confocal microscopy (9), or even with a slit lamp. “Demodex is best seen at the slit lamp using 40 × magnification,” says Teifi James (Figure 1). “In the absence of a 40 × magnification, a smartphone can even be used to zoom down the eyepiece to visualize the mites.” Once you know Demodex are present, the key to management is to reduce the mite burden. As lid hygiene is linked to Demodex infestation, daily eyelid scrubs (often with baby shampoo) have traditionally been recommended, but there’s evidence to show that this fails to effectively remove the mites (10). Tea tree oil is probably the most effective management option available today, and treatments containing the most active Demodex-killing component, 4-terpenieol (11), are now available. Finally, oral ivermectin was shown to be effective in eradicating Demodex in 12 patients with blepharitis (12).Where to next?

“Ophthalmologists are fighting a tidal surge of patients, and blepharitis usually takes a back seat in the presence of other more sight-threatening conditions,” notes Teifi James, adding that “In the UK, most slit lamps do not go up to 40 × magnification, meaning many ophthalmologists have never seen a Demodex mite, and are neither seeing nor treating this condition.” He adds, “We need to consider treatment options. The public are unaware that they are infested with parasites, and there may be an element of revulsion thatmay drive them to want to eradicate them completely.” There is still more to learn about the role Demodex plays in blepharitis (See Box: What We Don’t Know), but one thing seems clear: Demodex shouldn’t be overlooked when managing patients with unresolved blepharitis. Jesús Merayo has a simpler message: “If there is chronic lid inflammation with Demodex overgrowth that does not respond to conventional therapy, please remove the mites.” Teifi James is an ophthalmologist in Halifax, UK; Jesús Merayo Director and Professor of Ophthalmology at Instituto Universitario Fernández-Vega, University of Oviedo, Spain; and Serge Doan is an ophthalmologist at Hôpital Bichat et Fondation A. Rothschild, Paris, France.

References

- N Lacey et al., Biochem (Lond), 1, 2–6 (2009). PMID: 20664811. AE Rodriquez et al., Arch Soc Esp Oftalmol, 80, 635–642 (2005). PMID: 16311952. N Kabatas et al., Eye Contact Lens, [Epub ahead of print] (2016).PMID: 26783981. L Liang et al., Am J Ophthalmol, 157, 342–348 (2014). PMID: 24332377. N Lacey et al., Br J Dermatol, 157, 474–481 (2007). PMID: 17596156. J Liu et al., Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol, 10, 505–510 (2010). PMID: 20689407. YY Gao et al., IOVS, 46, 3089–3094 (2005). PMID: 16123406. KM Mastrota, Optom Vis Sci, 90, e172–174 (2013). PMID: 23670124. M Randon et al., Br J Ophthalmol, 99, 336–341 (2015). PMID: 25253768. YY Gao et al., Br J Ophthalmol, 89, 1468–1473 (2005). PMID: 16234455. S Tighe et al., Transl Vis Sci Technol, 2, 2 (2013). PMID: 24349880. FG Holzchuh et al., Am J Ophthalmol, 151, 1030–1034 (2011). PMID: 21334593.