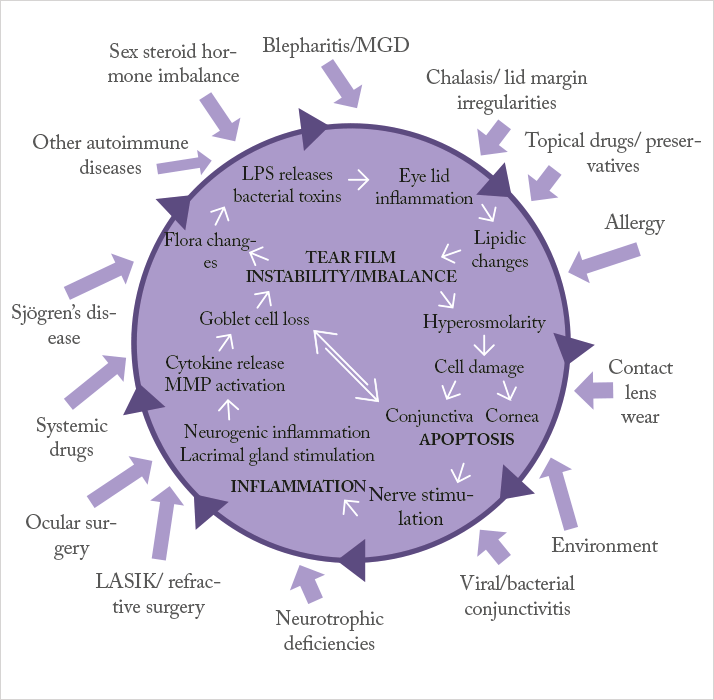

Managing dry eye disease becomes disproportionately more difficult as the severity of the disease increases: artificial tears and lubricants are not enough to help patients with severe dry eye disease. So what’s currently on offer? The management of patients with mild-to-moderate dry eye disease (DED) is relatively simple (1): symptom control with artificial tears and lubricants. However, once DED starts to become classified as severe, it becomes much harder to control; you need to address not just the symptoms, but also the cause: inflammation. Dampening the inflammation present in the ocular surface of patients with severe dry eye is key to achieving better outcomes. If we refer to Figure 1 – the vicious circle theory of dry eye – artificial tears and lubricants can help address the dry eye symptoms caused by the factors on the outside of the vicious circle, but they do nothing to address the disease processes at its core. Anti-inflammatory agents can get inside the vicious circle and disrupt it, resulting in a therapy that addresses the causes of DED, not just the symptoms (2).

In terms of topical anti-inflammatory treatment options for DED-related inflammation, there are essentially only two: corticosteroids and ciclosporin A. Corticosteroids have a rapid and powerful anti-inflammatory effect, and have been shown to improve both the signs and symptoms of DED (3). However, this can come at a cost: their ocular side-effect profile. In the short term, topical corticosteroid therapy use risks increasing patients’ intraocular pressure (4), and chronic use increases the risk of phakic patients developing cataract (5). This means that topical corticosteroid therapy is usually only a short-term measure, and one that requires close supervision by an ophthalmologist. The other option is ciclosporin-containing eyedrops. As ciclosporin controls inflammation by a completely different mechanism of action to that of corticosteroids, it avoids the potentially deal breaking side-effects of corticosteroid therapy, yet yields the anti-inflammatory efficacy that’s so needed in patients with severe DED. Although ciclosporin takes longer to produce an anti-inflammatory effect than corticosteroids, its use carries fewer risks and should be safe for chronic application. There is one big problem with ciclosporin eyedrops – availability. Until recently, there was no EU-approved, commercially available topical eyedrop formulation of ciclosporin. This meant that ophthalmologists either had to prescribe off-label, unapproved-in-the-EU commercial ciclosporin formulations obtained from international pharmacies, or rely on compounded formulations produced by some – mostly hospital – pharmacies. The latter option often comes with a number of issues that confound its use. With some exceptions, most compounded formulations require refrigeration and typically have a shelf-life of 7 days. When that is the case, the pool of patients that could benefit from such formulations is limited to those within a reasonable distance of a pharmacy that’s both willing and capable of producing such eyedrops. If patients live far away, and the formulation lasts only a week… then that’s just not an option. Clearly, for European patients with severe DED, there has been a considerable unmet need for a better option – an EU-approved, commercially available, ciclosporin-containing eyedrop.

Next month

Ikervis: the first and only EU-approved topical ophthalmic formulation of ciclosporin Very recently, the first – and only – topical ophthalmic ciclosporin product was approved in the EU: Ikervis. Next month, we will learn more about Ikervis, its innovative ciclosporin formulation, and the reason why the European Commission approved Ikervis for the following indication: the treatment of severe keratitis in adult patients with dry eye disease, which has not improved despite treatment with tear substitutes.

References

- G Van Setten et al., “Severe Dry Eye Disease – Facing the Treatment Challenges”, European Ophthalmic Review, 8, 87–92 (2014). C Baudouin, “A new approach for better comprehension of diseases of the ocular surface”, [Article in French], J Fr Ophtalmol., 30, 239–46 (2007). [No authors listed], “Management and therapy of dry eye disease”, Ocul Surf., 5, 163–78 (2007). R Jones, DJ Rhee, “Corticosteroid-induced ocular hypertension and glaucoma: a brief review and update of the literature”, Curr Opin Ophthalmol., 17, 163–167 (2006). PMID: 16552251. L. Bielory, “Ocular Allergy Treatment”, Immunol Allergy Clin N Am., 28, 189–224 (2008).