Corneal diseases are responsible for around 5 percent of blindness worldwide, but a shortage of corneas suitable for transplantation, particularly in the developing world, leaves patients waiting an average of five years for surgery (1). As a consequence, research teams around the world are in competition to develop artificial corneas that are suitable for mass production. Could 3D printing win the race?

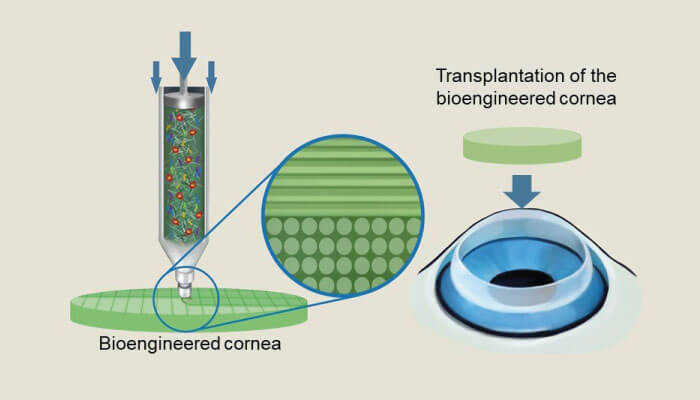

Dongwoo Cho, Professor of Mechanical Engineering at Pohang University of Science and Technology in South Korea certainly believes so. “Many artificial corneas and associated studies are based on synthetic biocompatible materials, yet studies have reported severe side effects,” says Cho. “To overcome such limitations, we have developed tissue-engineered corneas with 3D cell printing technology (2) (3).”

Cho’s team is not the first to trial such approaches, so what makes their work unique? “Some researchers have developed artificial corneas using collagen and alginate hydrogel, but the layers of these corneas are easily peeled apart, so the structure cannot be sustained,” he says. “Others have developed corneas with good cellular performance, yet the actual cornea remains opaque.”

To address these concerns, the team started fine-tuning the printing process, using different sized printing nozzles to manipulate the arrangement of collagen fibers – a process not without its own challenges. “One of our concerns was that different levels of sheer stress would cause cellular apoptosis, cell-cycle arrest, or cytoskeletal network alteration,” says Cho. Fortunately, the team were well prepared; they’d previously developed a qualified corneal bio ink and 3D printing system, so only minor modifications were required.

“We hypothesized that variance in sheer stress upon 3D printing would enforce the alignment of collagen fibrils in our cornea constructs,” says Cho. A prediction that appears to be correct: “Our printed cornea exhibited high capability in cellular alignment, and this resembled tissue-specific structural organization.” Indeed, the resulting lattice pattern showed high levels of similarity to native human corneal tissue – albeit after four weeks in rabbit in vivo models.

The next step is “make or break” for the team. Studies in beagles – a more developed animal model – are already underway with two aims: to improve the mechanical properties of the 3D-printed corneas and to ensure good biocompatibility. Cho is clearly confident in the long-term success of his team’s work. “With some further demonstration, we believe that this biomimetic cornea could be a substitute for patients waiting for transplant. We’ve also developed a 3D printing process that we believe to be easily replicable,” he says. “We believe our studies will contribute to a breakthrough in corneal transplantation practice around the world.”

References

- World Health Organisation, “Priority Eye Diseases: Corneal Oppacities” (2019) Accessed June 12, 2019.

- H Hong et al., “Compressed collagen intermixed with cornea-derived decellularized extracellular matrix providing mechanical and biochemical niches for corneal stroma analogue”, Mat Sci Eng, 103, 109837 doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2019.109837(2019)

- H Kim et al., “Shear-induced alignment of collagen fibrils using 3D cell printing for corneal stroma tissue engineering”, Biofabrication, 11, 035017 (2019). PMID: 30995622.