- The eyes of patients with glaucoma have always been challenging to operate on, as the disease and its medications can both induce adverse anatomical changes

- If a patient has a functioning bleb, and needs cataract surgery, inflammation and subsequent scarring can jeopardize the bleb

- There are a number of ways you can minimize the risk of bleb failure – and I list them in this article

- Glaucoma treatment has been rapidly evolving, and certainly the advancing technologies should start to improve our outcomes really soon.

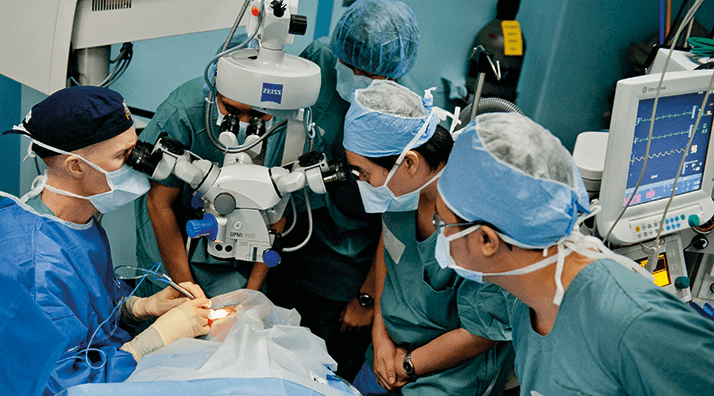

Performing cataract surgery in patients with glaucoma is almost inevitably more problematic than doing the procedure in similar patients without the disease. You may find pupil abnormalities, pseudo-exfoliation, posterior synechiae, weak or loose zonules, glaucoma medications might have given rise to a brittle capsule… and all are associated with intraoperative complications, including vitreous loss. It’s always been the case that doing the surgery is not the easiest option. During my residency program, one of the most challenging decisions I faced was: do I offer an extracapsular cataract extraction to patients with glaucoma and a pre-existing, functioning trabeculectomy? If I don’t, the cataract remains; if I do, I risk inducing bleb failure. It was also a difficult call in patients without previous glaucoma surgery, as the conjunctival manipulation risked poorer prognosis with any future filtering surgery.

Today’s cataract surgery in patients with glaucoma can be different…

Today, cataract surgery can be a good, initial surgical option for reducing intraocular pressure (IOP) in some patients with glaucoma (1). We can get IOP reductions in the range of 2–4 mmHg, with potentially greater reductions in patients with higher pre-operative pressures, and the procedure tends to produce the best results in patients with primary angle closure glaucoma. When we add micro-invasive glaucoma surgery (MIGS) to the cataract extraction, we can often – without the need for medication – reduce IOP down to around 15 mmHg. This is a great advance – even the ASCRS recognized this, awarding the 2014 Binkhorst medal to the glaucoma surgeon and investigator, Ike Ahmed, for his MIGS work. I would say that MIGS is here to stay: the surgery causes minimal trauma, has demonstrated a good safety profile, has no impact on refractive outcomes, and patients experience rapid recoveries. The future of MIGS looks promising, and with it the outcomes of the patients that are suitable to receive it.… but still difficult if prior trabeculectomy has been performed

Cataract surgery in eyes previously operated for glaucoma is a different story – particularly those with prior trabeculectomy or tube shunt surgery, and the approach to those patients is necessarily different. Here are seven key concepts you should bear in mind:1. Cataract surgery in eyes with functioning filtration blebs increases the risk of bleb failure Even nowadays phacoemulsification in an eye with a functioning trabeculectomy risks causing the trabeculectomy failure, principally due to scarring, inflammation, or complications thereof (2,3). When you consider that half of all patients who undergo trabeculectomy develop significant cataract within 5 years, it’s extremely important to have a comprehensive discussion with them about the risks involved, to ensure you truly have informed consent for the procedure. 2. Cataract surgery in eyes that have already undergone tube shunt surgery won’t reduce IOP When you’re performing cataract surgery in such eyes, you need to ensure that the tube shunt remains fully functional (4,5). Consider flushing the tube – or even a plate revision, in cases of borderline function. 3. The shorter the time between trabeculectomy and cataract surgery, the greater the risk of bleb failure The optimum timing is not known, but a delay of one to two years is protective against bleb failure (2,3). Understandably, there are many circumstances where cataract surgery has to be performed during the “high risk for bleb failure” period – but the general principle is: postpone the cataract surgery for as long as you can.

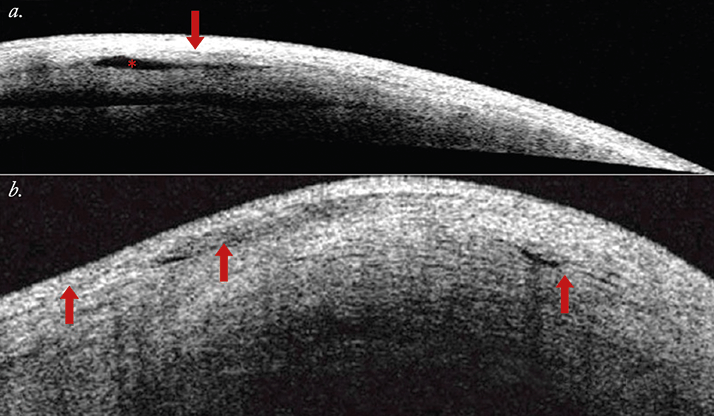

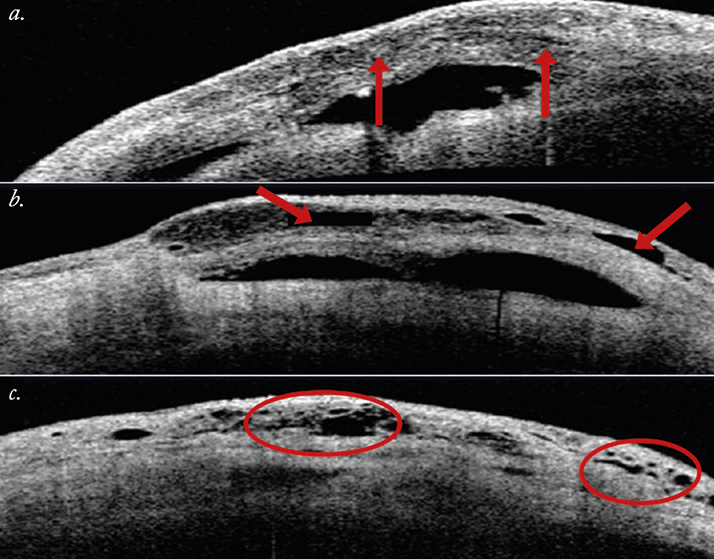

4. The higher the IOP prior to cataract surgery, the greater the risk of bleb failure The literature reports that 10–61 percent of trabeculectomies fail between 12–36 months after cataract surgery – but if you look more closely at the data, some of those trabeculectomies had already failed prior to the procedure – as many as 40 percent of cases in some studies (2,3). Clearly, we need to identify blebs with borderline function, as they are more susceptible to scarring and failing. How do you achieve this? Ultrasound biomicroscopy (UBM) or anterior segment (AS)-OCT (6,7), if you can (Figures 1 and 2) – with UBM, you want to see a visible route under the scleral flap and a low-reflective bleb – if you cannot visualize a tract under the flap or you see a highly reflective bleb surface – the bleb is not working properly (8). With AS-OCT, you’re looking for multiform reflectivity, multiple internal layers, subconjunctival separation and microcysts as a sign that the bleb is functioning. Having said that, you can’t blame cataract surgery for producing bleb failure in a patient with a previous trabeculectomy, who was using four drugs to keep IOP around 21 mmHg before phacoemulsification. Nevertheless, if you are able to identify those borderline blebs, you can use injections of 5-FU or mitomycin C (to reduce scarring; Online Video 1) – or even needling (Online Video 2) to keep them functioning. In patients with underfunctioning blebs, simultaneous phacoemulsification and needling has been reported with bleb recovery in 89 percent of patients (9).

5. The more atraumatic the cataract surgery, the less risk of bleb failure You really need to do as little intraoperative iris manipulation as possible, in order to minimize the risk of inflammation and bleb scarring (2,3). The key point here is to stay away from the bleb. When performing cataract surgery, use a temporal, clear corneal approach, ensuring that the sites are at least three clock hours apart. In essence: do as little as possible – but be prepared for everything! 6. Use aggressive anti-inflammatory treatment in the postoperative period I usually use a pretty aggressive post-operative anti-inflammatory regimen: steroids for eight to twelve weeks (with slow tapering), and I always prescribe non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) for about three weeks after surgery, principally to dampen down any iris manipulation-related inflammation. I’d also suggest you consider 5-FU injections in the postoperative period in order to increase the success of the bleb. 7. Improve your gonioscopy skills! MIGS is advancing at a breathtaking pace – the technology is here to stay, and with the data that’s currently coming in, it’s easy to envisage that the future treatment of glaucoma will include the implantation of a MIGS device, with or without cataract surgery – so your gonioscopy will need to be in tip-top condition when performing these procedures! Dealing with cataracts in patients with glaucoma has always been challenging, and remains, even today, a difficult situation that needs careful and considerable attention in order to deal with it. But even today, if you make the right choices, most of the time, you can get good results. The future looks even brighter – the field of MIGS is expanding, many new devices and therapeutic options for glaucoma are under development, which holds promise of even better outcomes compared to the ones available today.

Juan Mura is an instructor for the Ophthalmology Department at the Universidad de Chile in Santiago, Chile.

References

- S.L. Mansberger, M.O. Gorfon, H. Jampel, et al., “Reduction in Intraocular Pressure after Cataract Extraction: The Ocular Hypertension Treatment Study”, Ophthalmology 119, 1826–1831 (2012). doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.02.050. R. Husain, S. Liang, P.J. Foster, et al., “Cataract surgery after trabeculectomy: the effect on trabeculectomy function”, Arch. Ophthalmol., 130, 165-170 (2012). doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2011.329. R.G. Mathew, I.E. Murdoch, “The silent enemy: a review of cataract in relation to glaucoma and trabeculectomy surgery”, Br. J. Ophthalmol. 95, 1350-1354 (2011). doi: 10.1136/bjo.2010.194811. H.Y. Patel, H.V. Danesh-Meyer, “Incidence and management of cataract after glaucoma surgery”, Curr. Opin. Ophthalmol. 24, 15-20 (2013). doi: 10.1097/ICU.0b013e32835ab55f. C.A. Bhattacharyya, D. WuDunn, V. Lakhani et al., “Cataract surgery after tube shunts”, J. Glaucoma, 9, 453-457 (2000). X. Wang, H. Zhang, S. Li, N. Wang, “The effects of phacoemulsification on intraocular pressure and ultrasound biomicroscopic image of filtering bleb in eyes with cataract and functioning filtering blebs”, Eye, 23, 112-116 (2009). T. Yamamoto, T. Sakuma, Y. Kitazawa, “An ultrasound biomicroscopic study of filtering blebs after mitomycin C trabeculectomy”, Ophthalmology, 102, 1770-1776 (1995). M.B. Khamar, S.R Soni, S.V. Mehta et al., “Morphology of functioning trabeculectomy blebs using anterior segment optical coherence tomography”, Indian J. Ophthalmol., 62, 711–714 (2014). doi:10.4103/0301-4738.136227. N. Kasahara, S.A. Sibayan, M.H. Montenegro, et al., “Corneal incision phacoemulsification and internal bleb revision”, Ophthalmic Surg. Lasers, 27, 361-366 (1996).