The past fifty years have seen significant changes in the practice of ophthalmology. New diagnostic tools, pharmacological interventions, and surgical techniques have all been developed, and clinical trial and post-marketing surveillance data have almost always shown these to be of benefit to patients. However, patients only receive interventions if screening catches them or they present themselves to a physician, and drugs only work if patients take them as directed. Regimen non-compliance can strip the efficacy from even the most effective therapies.

So, have the advances of the last half-century percolated sufficiently through the health care system to make a difference at the population level? That question has been answered with a resounding “yes” in a recently-published analysis of long-term trends in glaucoma-related blindness (1). The Olmsted County Study (OCS) data used was originally designed to follow the incidence of cardiovascular events, and was subsequently expanded to cover other disorders. The database has almost complete local medical history coverage of patients presenting to Mayo Clinic hospitals in the Olmsted County region of Minnesota, dating back for over six decades. Mehrdad Malihi, an ophthalmologist at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN, and his colleagues analyzed OCS medical records in order to determine the historical incidence of open-angle glaucoma (OAG) diagnoses over two OCS time periods: 1965 to 1980 and 1981 to 2000.

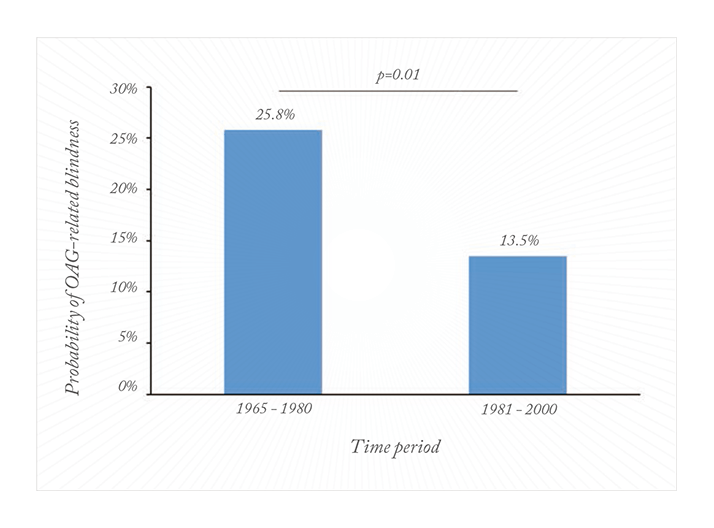

Compared with the earlier period, the probability of glaucoma leading to blindness in at least one eye in the later period fell by almost one-half (see Figure 1). Between 1965 and 1980, the probability of OAG-related blindness was 25.8 percent; this dropped to 13.5 percent in the period 1981 to 2000 – and the difference was highly significant (p=0.01).

Progression to blindness also slowed significantly. The incidence of blindness within 10 years of first glaucoma diagnosis was reduced from 8.7 per 100,000 for patients in the LBJ-Nixon-Carter era, to 5.5 per 100,000 for patients diagnosed under the Reagan-Bush-Clinton administrations (p=0.02). As for many other diseases, older age was a significant risk factor for blindness (p<0.001), although gender was not. This study demonstrates that the interventions made in timolol era worked (timolol was first approved for use in the US for glaucoma treatment in 1978). Russell Young, Chairman of the International Glaucoma Association, in commenting on how the trend might continue, observed that, “The combination of improved surgery and more convenient and effective eye drops may lead to further reductions in these figures in the future. However, these results are still highly dependent on the patient’s commitment to using their drops daily, which continues to be a significant issue. Thankfully, with patient commitment, this means the vast majority of patients with glaucoma can look forward to a decent quality of life for the rest of their days.”

References

- M Malihi, ER Moura Filho, DO Hodge and AJ Sit, “Long-Term Trends in Glaucoma-Related Blindness in Olmsted County, Minnesota”, Ophthalmology, 2013 (ePub ahead of print).