Although bionic technology already exists within ophthalmology, the journey towards commercial viability has been problematic. One of the major players involved has already veered dangerously close to bankruptcy; Second Sight Medical Products, which developed the only extant FDA-approved bionic eye implants (1), had to discontinue both their Argus I and Argus II models in 2019 due to financial difficulties, leaving more than 350 blind users with implanted technology that was essentially obsolete (2). With its stock price rapidly falling, Second Sight’s commercial future looked bleak until February 2022, when the company announced a merger with biopharmaceutical company Nano Precision Medical (NPM).

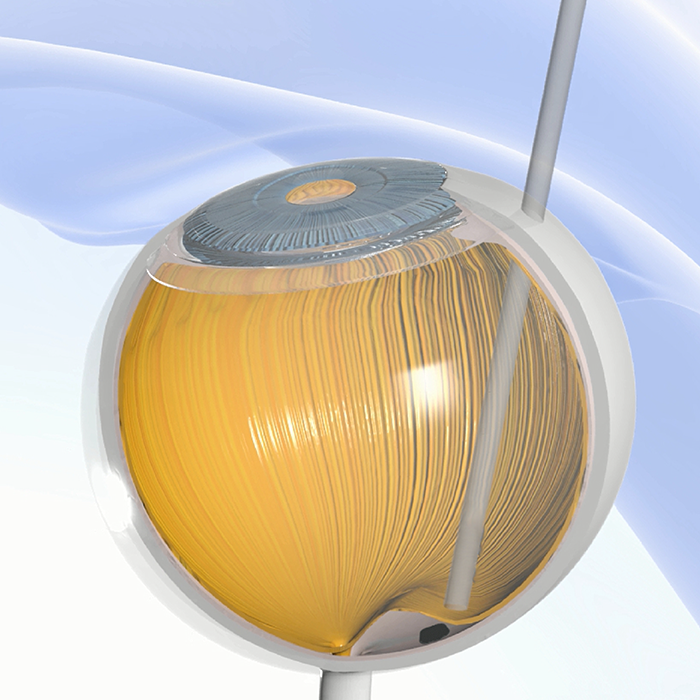

Despite these setbacks, companies outside the US continue to develop their own retinal implants. In Paris, for instance, Pixium Vision is currently undergoing feasibility trials for their Prima System (3) – an implant proposing to offer age-related macular degeneration (AMD) patients bionic vision. Pixium’s CEO, Lloyd Diamond, believes its device represents further advances for the technology: “The Prima System has demonstrated restoration of form vision, and that’s very important because other technologies created phosphenes, but now we are talking about the patients actually being able to see forms and shapes.” As if reiterating Diamond’s claims at the developmental capabilities of such technology, the market for retinal implants remains set to see a “steady growth rate of 7.5% by 2031” (4).

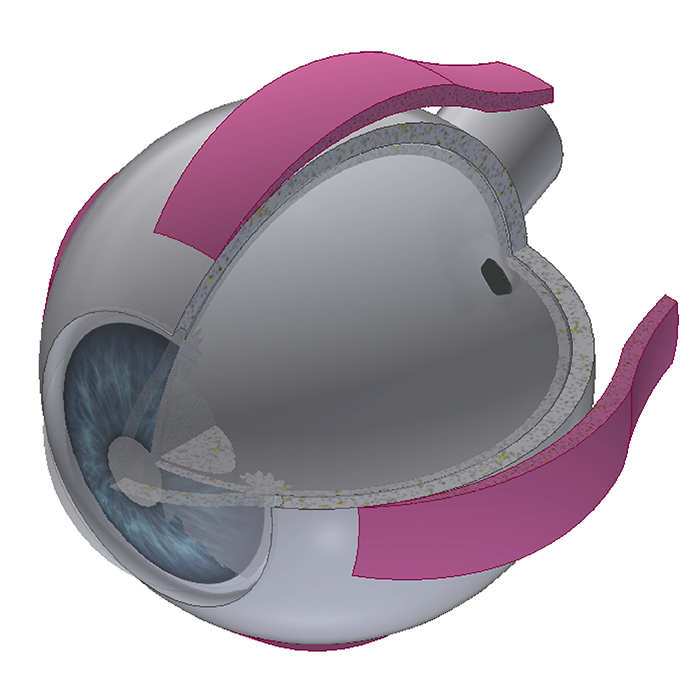

Running parallel to retinal implant development, research into neural implants – which bypass the visual processing of the eyes to send signals straight to the brain’s visual cortex – continue to make headway. Indeed, before Second Sight’s 2022 merger, the company had already begun to divest R&D time into the Orion Visual Cortical Prosthesis System (5).

Speaking of whether neural implants might indeed supplant retinal implants, Yan Tat Wong - Biomedical Engineering Course Director at Monash University and lead author of a Journal of Neuroengineering study investigating how more efficient phosphene mapping might improve neural prosthetic outcomes (6) – elaborates on the differences between the two types. “I don’t think there is a simple ‘better or worse’ when comparing retinal to cortical implants. The cortical implants are typically targeted towards blindness conditions that cannot be aided via retinal prostheses, so incidences where the optic nerve or the ganglion cells in the eye are damaged or removed,” he explains. “Cortical implants are currently more invasive than retinal implants, so I think they should be viewed as a complimentary technology. In terms of engineering development, the cortical approach does provide some advantages in that the surface area representing central vision in the brain is much larger than on the retina, which just makes designing the implant electrodes slightly simpler.”

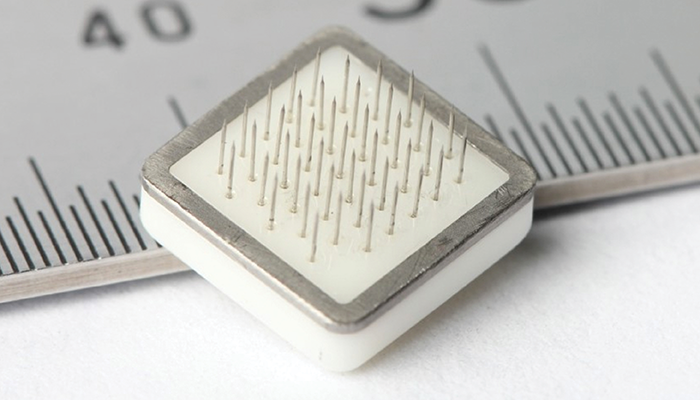

However, Wong is adamant there’s still work to be done. “The last few decades have seen amazing leaps forward in technology, but major ‘discovery science’ questions remain unanswered,” he says. “My prediction is that we will see a greater linking between implant development – smaller implants with more electrodes that don’t damage bodily tissue – and the neuroscience of how our brains work.”

With caveats, specialists like Wong appear confident in the evolution of these implants, but the near future of the technology remains uncertain. As witnessed with Second Sight, the principal hurdle to mainstream market adoption is the issue of scalability. “The challenge isn't so much in the performance of the technology; the challenge will be in the ability to efficiently manufacture the implant,” says Diamond. “Our next-generation implant will have up to 10,000 electrodes and these electrodes are three-dimensional; and so the industrialization of the technology will be our primary challenge.”

Can this mass production challenge be overcome by the companies still heavily invested in bringing the technology to market? Well, if utilitarianism edges forward as the primary motivating factor behind production, implants – both retinal and neural – may eventually result in vision restoration for people all over the world.

References

- Forbes, “FDA Approves First Bionic Eye,” (2013). Available at: https://bit.ly/3G0BQjn.

- IEEE Spectrum, “Their Bionic Eyes are now obsolete and unsupported,” (2022). Available at: https://bit.ly/3SI3sRL.

- Pixium Vision, “Prima Bionic Vision System,” (2023).

- Business Wire, “Revolutionizing Vision Care: Global Artificial Retina Market Grows Amid Rising Prevalence of Retinal Diseases,” (2023). Available at: https://bwnews.pr/47g9LAu.

- Cortigent, “Orion,” (2023). Available at: https://bit.ly/3MHxBNe.

- HZ Wang, YT Wong, “A novel simulation paradigm utilizing MRI-derived phosphene maps for cortical prosthetic vision,” J Neural Eng, 20, 046027 (2023). PMID: 37531948.