- Monthly anti-VEGF agent dosing generates optimal visual outcomes – but this comes at a cost

- Visits are a burden on patients, carers, and healthcare resources

- Pro re nata regimens can help with this, but still require monthly monitoring

- Treat-and-extend adds considerable complexity to scheduling appointments, but for many patients, the extension of treatment intervals decreases the burden of visits to all involved

There is a big difference between the clinical trial setting and the real world. Clinical trials are closely monitored, and patients are actively participating in the study – regimen adherence is high and outcomes are as good as can be expected. But the real world is different: patients are less stringently selected, their adherence is poorer, and inevitably, so are their outcomes. There is an additional layer of complexity: shrinking healthcare budgets. By way of an ophthalmic example, the pivotal clinical trials that formed the basis of the regulatory approval of ranibizumab in wet AMD used fixed dosing regimens – and yielded excellent visual outcomes (1,2). But the resources that need to be devoted to monitoring patients’ maculae, drug and administration costs are not trivial, and so the pressure is to try to extend the dosing intervals in patients that can tolerate this.

Pro re nata isn’t enough

A modification of the fixed dosing model was a monthly monitoring scheme with pro re nata (PRN) dosing, which appeared to provide results comparable with monthly dosing regimens (3). This held the potential of reducing the number of injections required, but it still meant patients needed to be monitored monthly. In the UK (where I am based), the practicalities of monthly dosing regimens – or even monthly monitoring with PRN injections in our National Health Service (NHS) – are limited. There are 40,000 new cases of wet AMD diagnosed every year here (4), and this figure will only continue to rise (5). A staggering 94 percent of NHS trusts with eye clinics say there are significant capacity issues and they are understandably concerned about not being able to meet the rising demand for services (6). A report by the Royal College of Ophthalmologists suggests that the thing most units are concerned about is accommodating reassessment appointments (7), although the pressures on the system will vary according to each individual unit’s resources. The capacity issue is compounded by the fact that year upon year, discharge rates amongst patients with wet AMD have not matched the number of new patients entering the scheme.Treat-and-extend

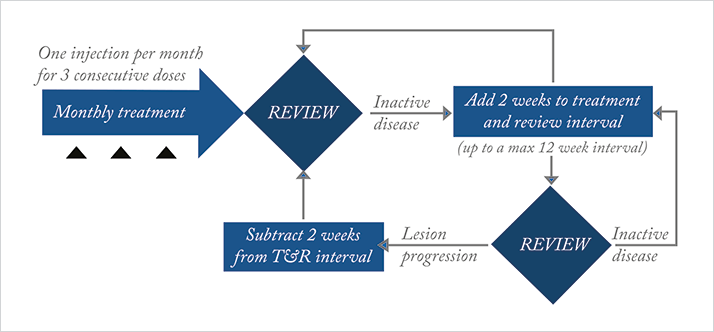

One approach to try and tackle the ever-increasing number of patients within an AMD service is to modify the treatment paradigms to allow extended intervals between monitoring visits as well as treatments (as long as visual and anatomic stability is achievable and maintainable). Various models have been tried to address this, including an approach to treat patients when stable, and then extend the monitoring interval – the so-called “Treat-and-extend” regime. The approach has two objectives: 1) to ease burden on patients, staff and healthcare resources by reducing the number of visits; 2) once the macula has been stabilized, to ensure continued treatment of the dry macula at an interval optimized to that patient. The aim is to prevent recurrences of fluid and hemorrhage, ensuring that the visual benefits already gained with previous fixed dosing regimens are maintained.We have started a treat-and-extend scheme, with selected patients being treated with ranibizumab in our service (Figure 1). Our regime involves administering the standard loading phase of three monthly injections, and then on review a month later if the lesion is inactive, the patient is treated with a stabilizing injection, whereupon the monitoring interval is extended to six weeks. At each subsequent review, if the disease is inactive, the treatment interval is increased by two weeks until a maximum interval of 12 weeks. At this point, if two 12-week intervals are achieved, a decision is made based on the patient’s previous activation history whether to monitor and extend (rather than give a stabilizing injection), or whether to continue 12-weekly, fixed dose injections. At any point during the treatment schedule outlined above, if the patient reactivates, retreatment is started – but the exact regime depends heavily on the degree of new activity and length of the interval that the patient has managed to achieve. We will expand this further in the examples to follow, but in essence, the treat-and-extend protocol that we provide – whilst starting out as a quite a prescriptive regime – has ended up being a more bespoke service that deals with each patient on an individual basis. I believe this approach provides a better treatment pathway overall.

Naïve patients

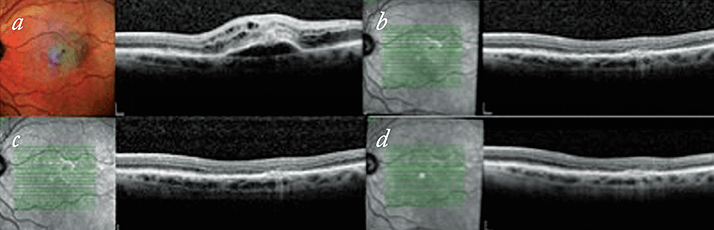

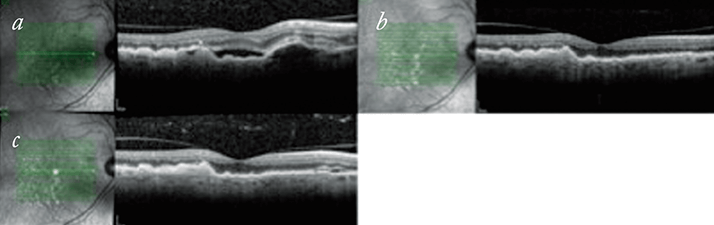

We have started treat-and-extend have on treatment-naïve patients and found responses to be variable. Figure 2 shows a patient’s response from their baseline OCT images through to a 12-week extension. Treat-and-extend is not suitable for all patients, with some patients not stabilizing after the initial three injections and therefore not able to start on the regime for some months (Figure 3). In other patients, a degree of stability can be achieved after six or eight weeks, but when there is recurrence, the decision on best retreatment strategy is made based on the patient’s previous recurrence record and the degree of activity noted. So some patients will be put back on a loop of three injections for large degrees of activation (although we have found that these situations are uncommon). More commonly the recurrences are small and patients are either treated and kept on the same length of extension, or have their extension period shortened by two weeks. On the subsequent review, if stability is achieved, but the patient is known to recur if the extension period is stretched any longer, then the patient may be kept on a fixed dosing scheme at six, eight or 10 weekly intervals for a period of time.

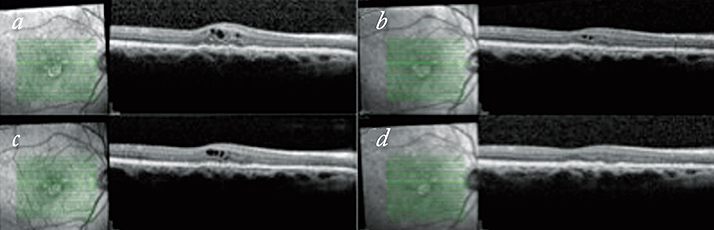

In some respects we have found that it is the patients started on the treat-and-extend regimen after previously being on a PRN regimen that have benefitted the most. Figure 4 shows a patient who had previously required monthly review appointments and unpredictable treatment schedules, with periods of watching and waiting for fluid recurrences. On a treat-and-extend regime they are maintaining stable visions and have a dry macula. In addition to the obvious time and cost benefits to patients, their carers and families, there are other practical benefits to running a treat-and-extend system. As already mentioned, for those patients that do stabilize and manage to progressively extend their monitoring phase, the number of visits is reduced. In a one-stop clinic set up, injection numbers can be rather variable using a PRN regime, but they are predictable in a treat-and-extend regime, thus allowing better use of resources.

Additional complexity

There are, however, multiple challenges in establishing and running an efficient treat-and-extend service. The treatment algorithms are quite complex, and the coordinating staff who book appointments for patients need to be familiar with the intricacies of the protocol in order to arrange the appointments correctly. The system itself is best suited to a one-stop setting, with monitoring and injection on the same day, but if the gap between assessment and injection can be minimized, this does not exclude running a treat-and-extend regime in a two-stop system. Furthermore, not all patients stabilize adequately to allow an extension phase. So monthly monitoring with PRN dosing regimens will need to run alongside the patients on treat-and-extend regimens as well as any patients who may be on fixed dosing regimens, making the clinic coordinator’s job very complicated.Since treatment responses can be so variable in wet AMD, bilateral cases can be difficult to accommodate on a treat-and-extend regime, but not necessarily excluded. Even bilateral cases can be managed with treat-and-extend protocols. Good clinic coordination is required, and you need to ensure that the monitor and treatment duration is kept to the shorter interval of the two eyes, but it is possible. Also, second eye monitoring is made more difficult when the monitoring phase extends out, but we are careful to counsel patients about self-monitoring the other eye. Activation of the second eye can bring complicated treatment regimes when both eyes have to be accommodated as bilateral cases described above. There will be cases or situations however, when it may be worth considering reverting back to monthly PRN visits to keep the booking of appointments simple and avoid confusion for the patients and staff. In addition, the notion of treating a dry macula does not sit comfortably with some clinicians – especially in view of suggestions that continued used of anti-VEGF agents may accelerate atrophic changes. But overall, we have found that for certain patients, a treat-and-extend regime works well. This system allows treatment regimens to be tailored specifically to each patient, ensuring that care is optimized to their disease pattern and responses.

Niro Narendran is a consultant ophthalmologist at the Eye Infirmary, Royal Wolverhampton Hospitals NHS Trust, Wolverhampton, UK.

References

- PJ Rosenfeld, et al., “Ranibizumab for neovascular age-related macular degeneration”, N Engl J Med, 355, 1419–1431 (2006). PMID: 17021318. DM Brown, et al., “Ranibizumab versus verteporfin for neovascular age-related macular degeneration”, N Engl J Med, 355, 1432–1444 (2006). PMID: 17021319. AE Fung, et al., “An optical coherence tomography-guided, variable dosing regimen with intravitreal ranibizumab (Lucentis) for neovascular age-related macular degeneration”, Am J Ophthalmol, 143, 566–583 (2007). PMID: 17386270. CG Owen, et al., “The estimated prevalence and incidence of late stage age related macular degeneration in the UK”, Br J Ophthalmol, 96, 752–756 (2012). PMID: 22329913. DC Minassian, et al., “Modelling the prevalence of age-related macular degeneration (2010-2020) in the UK: expected impact of anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) therapy”, Br J Ophthalmol, 95, 1433–1436 (2011). PMID: 21317425. RNIB, “Saving money, losing sight. RNIB campaign report”, November 2013, http://bit.ly/RNIBreport. Last accessed September 10, 2015. W Amoaku, “The Royal College of Ophthalmologists. Maximising Capacity in AMD Services”, July 2013. Available at: http://bit.ly/maxcapAMD. Last accessed September 10, 2015.