Myopia is one of the world’s most common eye disorders, with a prevalence of about 40 percent in Europe (1) and the United States and up to 90 percent in developed Asian countries (2). It’s a dramatic increase from numbers seen only a few decades ago, and while the refractive consequences of high myopia are easily corrected, the disease state brings with it an increased risk of retinal detachment, macular degeneration, cataract and glaucoma. This is especially true for children with rapid myopia progression – so investigators based in Singapore decided to see if they could somehow slow the development of myopia pharmacologically.

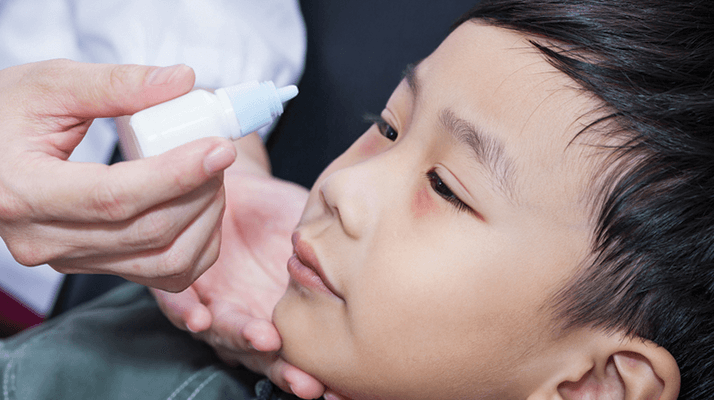

To do so, they turned to a drug first isolated from deadly nightshade: atropine. The drug has been shown to inhibit the axial growth of the eye (3), directly combating the development of myopia. But when given at high concentrations, atropine can have unpleasant side effects such as blurry, light-sensitive vision (resulting from pupil dilation), allergic conjunctivitis and dermatitis (4). In an effort to avoid these consequences, the researchers investigated the potential of low-dose atropine to slow the progression of myopia while (hopefully) minimizing side effects (5). The ATOM2 study began in 2006, with 400 children aged between six and 12 years being randomly assigned to receive a once-nightly atropine dose of either 0.5, 0.1 or 0.01% in a 2:2:1 ratio for a period of 24 months, after which atropine treatment was halted and children were monitored for a further 12 months. Children whose myopia progressed by -0.5 D or more during this washout period were restarted on atropine 0.01% for a further 24 months.

In a previous study of atropine use for myopia progression reduction, ATOM1, 1% atropine administration slowed myopia progression in children by 50 percent, compared with placebo (5). But when the first results of ATOM2 were published, the lowest dose of atropine proved most effective; children who received the 0.01% dose were less myopic at three years from baseline than those who received either the 0.1 or 0.5% doses. And so far, the 0.01% dosage appears safer for use in children than the higher doses (up to 1%) previously tested, minimizing pupil dilation and near-vision loss.

More research is needed to determine which children are the best candidates for the treatment (as not all respond), and to establish the safest and most effective starting age and total duration of atropine therapy. The study’s lead investigator Donald Tan said, “Combined with other interventions, this treatment could become a great ally in preventing myopia from causing serious visual impairment in children worldwide” (7).

References

- S Vitale, “Increased prevalence of myopia in the United States between 1971-1972 and 1999-2004”, Arch Ophthalmol, 127, 1632–1639 (2009). PMID: 20008719. IG Morgan, “Myopia”, Lancet, 379, 1739–1748 (2012). PMID: 22559900. VA Barathi et al., “Effects of unilateral topical atropine on binocular pupil responses and eye growth in mice”, Vision Res, 49, 383–387 (2009). PMID: 19059278. A Chia et al., “Atropine for the treatment of childhood myopia: safety and efficacy of 0.5%, 0.1%, and 0.01% doses (Atropine for the Treatment of Myopia 2)”, Ophthalmology, 119, 347–354 (2012). PMID: 21963266. L Tong, et al., “Atropine for the treatment of childhood myopia: effect on myopia progression after cessation of atropine”, Ophthalmology, 116, 572–579 (2009). PMID: 19167081. A Chia, et al., “Five-year clinical trial on atropine for the treatment of myopia 2: myopia control with atropine 0.01% eyedrops”, Ophthalmology, [Epub ahead of print]. PMID: 26271839. American Academy of Ophthalmology, “Nearsightedness progression in children slowed down by medicated eye drops”, (2015). Available at: http://bit.ly/1Hq6Vvy. Accessed November 26, 2015.