Patching might be the mainstay of treating amblyopia, but it isn’t perfect. The dominant eye is unused; both eyes aren’t taught to work together, and there’s no guarantee of a decent outcome at the end of the process – up to half of all patched children never achieve normal visual acuity (VA) at the end of even lengthy courses of treatment, and normal binocularity is rarely achieved. This need for a better approach to amblyopia treatment has spurred on a number of research teams to try and do something a little bit smarter.

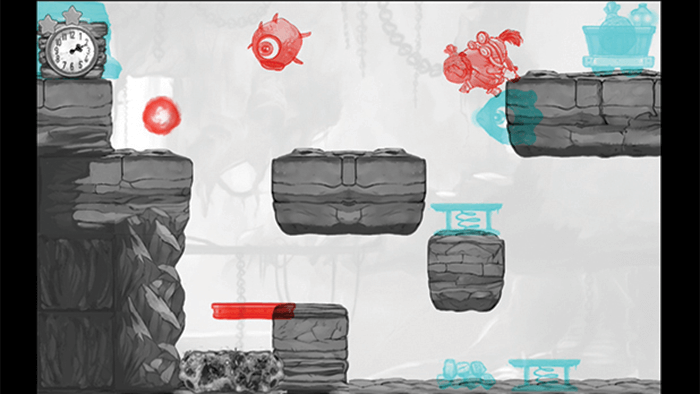

But there are alternatives to patching – binocular approaches to treating anisometropic and strabismic amblyopia have shown promise. The basic principle is this: high-contrast images are presented to the amblyopic eye; low-contrast images are presented to the fellow eye. Together, the images form a binocular percept. But keeping young, amblyopic children engaged with these eye training tasks isn’t easy – which is why many researchers, including those at the Retina Foundation of the Southwest, Dallas, Texas, have turned to computer games to hold their attention during this dichoptic “contrast-rebalancing” training (1). Their game, “Dig Rush,” sees players direct miners to dig for gold, while navigating obstacles and avoiding threats like fire and monsters. Red-green anaglyphic glasses are worn to enable each eye to see different contrast elements of the game. But does it work as well as patching? The team performed a randomized, controlled trial to find out. Twenty-eight children with amblyopia aged 4–10 years were randomized in a 1:1 ratio to either gameplay or patching. After two weeks, mean BCVA improved by 1.5 lines in those who played the game – more than double the improvement seen in the patching group (0.07 lines, p=0.02). Children who were patched could switch to the game after two weeks, and by week four, their visual gains matched those achieved by the children originally randomized to the gameplay group. “Here, both groups improved by 1.7 lines in just four weeks, and incredibly, 39 percent recovered normal vision for their age,” notes Krista Kelly, lead author on the paper (1). “This may be attributed to the excellent compliance with this engaging game – children responded very well and genuinely enjoyed trying to beat all of the levels.” There’s still more work to be done. Kelly explains “it’s extremely important to determine how contrast changes should occur, how long treatment should last, and how children will respond long-term.” As well as investigating how to achieve maximal VA improvements, the group hopes more people will develop games aimed at treating amblyopia. “Most children finished our game’s 42 levels within the 4-week study treatment period – providing a variety of games could help with long-term treatment. We also need to explore options such as animations for younger children who cannot play the games.”

References

- KR Kelly et al., “Binocular iPad game vs patching for treatment of amblyopia in children: a randomized clinical trial”, JAMA Ophthalmol (2016). [EPub ahead of print]. PMID: 27832248.