- The IC-8 small aperture IOL has been available in Europe since 2014 and provides a novel method of giving patients undergoing cataract surgery “depth of focus”

- The interim results of a post-marketing clinical follow-up study are reported here

- The lenses also seem more forgiving of residual astigmatism or deviation from target refraction

- Surgical procedures on the retina can still be performed with the IC-8 in situ with minimal additional difficulty; stereopsis is unaffected

Patients who wish spectacle-independence following cataract surgery can choose from an ever-increasing number of premium – bifocal and trifocal – intraocular lenses (IOLs) to replace their clouded, crystalline lenses. No IOL available today can match the performance of a clear natural lens, but these premium IOLs do utilize some very complex and clever optical designs to guide the incoming light and give patients multiple fixed optical foci. However, this multifocality comes at a price: compared with monofocal IOLs, patients receiving multifocal IOLs tend to report greater levels of photopic phenomena, lower contrast sensitivity and decreased visual range.

There is an alternative approach: small-aperture optics. Initially deployed as a presbyopia-correcting corneal inlay, but now incorporated into an IOL, the small-aperture IOL (IC-8, AcuFocus Inc., Irvine, California) offers a new approach to providing good visual quality across a range of distances. Like the KAMRA corneal inlay before it, these lenses have an opaque annular mask that blocks unfocused peripheral light rays, but still allows paraxial central light rays to penetrate through its aperture. The IC-8 IOL has been under post-market evaluation in Europe for over a year now, and I am involved in a post-approval clinical follow-up study that has assessed the visual outcomes of patients who have received it.

The IC-8 Post-Market Study

The IC-8 IOL Post-Market Study (1) involves the contralateral implantation of the IC-8 small-aperture IOL in the non-dominant eye, plus any aspheric, colorless monofocal IOL in the dominant eye. The IC-8 IOL is a one-piece hydrophobic acrylic IOL with a 5 μm hydrophobic mask, 3.23 mm in diameter with a 1.36 mm aperture. The surgical technique – a minimally invasive cataract removal and lens-in-the-bag implantation – is standardized across 12 sites in Spain, Italy, Belgium, Norway and Germany (Video: http://bit.ly/ic-8). Ultimately, our goal is to enroll 130 subjects, who are evaluated at one, three and six months postoperatively. At the moment, we have interim results from the one- and three-month evaluations – but they give us a good idea of the direction our final results might take.Study outcomes

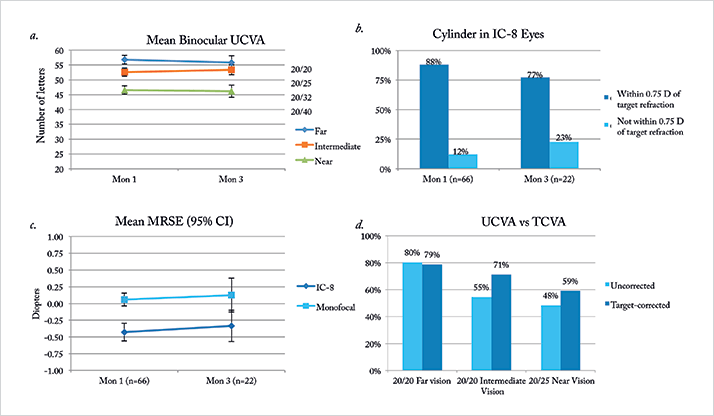

So far, we’re seeing binocular uncorrected visual acuities with a mean of about 20/20 far and intermediate and 20/32 near – results that have remained stable at one and three months post-implantation (see Figure 1a). In terms of postoperative refraction, we recommend that patients have a spherical refraction target of -0.75 D – but we believe that small-aperture lenses have the ability to correct cylinder, so we have been allowing enrollment up to 1.75 D of cylinder. We’ve found that 88 percent of our patients have a cylinder between -0.75 and 0 D after one month, and 77 percent maintain that after three months (see Figure 1b). We’re also seeing that a cylinder of as much as 1.25 D has little to no effect on visual acuity in IC-8-implanted eyes – which is really interesting, because this level of cylinder can have a dramatic effect in many lenses. This has the potential to simplify things for the surgeon, as it minimizes the guesswork involved in getting the lens on a certain axis, and a slight deviation won’t degrade the optics and can alleviate the potential for surgically induced astigmatism. Figure 1c compares postoperative refraction in the dominant (monofocal) and the non-dominant (IC-8) eye. Our target for the monofocal eye was 0 D of refractive error; for the eye receiving the small-aperture lens, we aimed for -0.75 D (“target correction”). A small amount of myopia in that eye improves near and intermediate visual acuity without compromising distance vision – although patients with monovision would see a decrease in distance visual acuity with such a target, those with the small-aperture lens are still able to achieve 20/20. At the moment, we’re currently achieving a mean error of about -0.37 D in that eye – so it’s not quite where we want it yet, but because the lens is tolerant to small deviations, the results are good nonetheless. After the procedure, we compared patients’ uncorrected to target-corrected vision and found that, with our target correction, a higher proportion of patients achieved 20/20 far and intermediate and 20/25 near visual acuity (see Figure 1d).

Interesting cases Visualizing the retina

One question that comes up when using a small-aperture IOL is: does it interfere with a clinician’s ability to do posterior segment diagnostics or retinal surgery? To address that, I’ve performed a range of procedures. For instance, I’ve performed a macular membrane peel – a challenge because of the surgeon’s need for pristine stereoacuity to verify membrane depth. I wanted to investigate whether or not the mask within the IOL would interfere with stereopsis, but it doesn’t. It allowed me to perform not only the epiretinal membrane peel, but also pars plana vitrectomies for diabetic retinopathy and central and peripheral retinal detachment. I’ve also tried three different systems for visualization during vitrectomy and seen no greater issues with any of them. It’s not as easy to perform these procedures as it would be with an ordinary monofocal IOL, but any posterior segment surgeon is capable of performing them after some adjustments

TASS

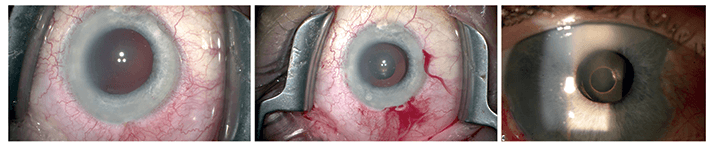

In one case, a 62-year-old patient presented after toxic anterior segment surgery (TASS) following complicated cataract surgery and subsequent IOL explantation. The patient was experiencing corneal decompensation with significant glare, excessive photophobia and 14 D of refractive error due to aphakia. With no improvement three months after surgery, the patient had no range of vision and was at risk of needing a corneal transplant. With the intention to minimize the dysphotopsias induced by the corneal changes, including irregularity, a small-aperture lens was implanted in the ciliary sulcus (see Figure 2). Four months after implantation, the patient’s near and distance acuity were each 20/25, and the refractive error was only 0.25 D. Small-aperture lenses are a good solution for patients with irregular corneas who might otherwise experience higher-order aberrations, because they allow central rays to pass through the aperture while limiting the peripheral rays that can impact focus.

Use as a secondary IOL to treat injury-induced dysphotopsia and glare

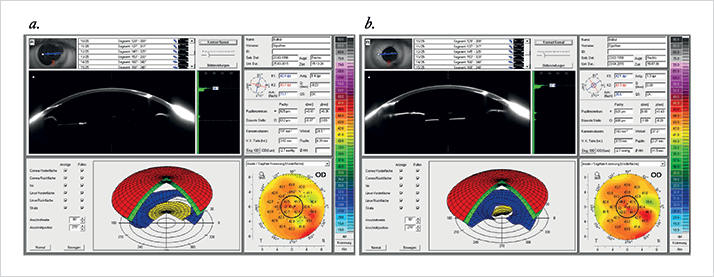

Another interesting case involved surgery on a 17-year-old patient’s eye after a wire caused paracentral perforation of the cornea, lens and iris. The cornea was sutured, the lens removed and an anterior vitrectomy had to be performed. Three months after surgery, the patient continued to complain of significant glare, light sensations and photophobia. Ordinarily, a surgeon might suture the iris and implant a secondary monofocal IOL – but this solution doesn’t address the irregular cornea (which can cause dysphotopsia and decreased vision), prevents pupil dilation for fundus visualization, and causes the loss of near and intermediate vision in a young, binocular patient. So instead, I opted to implant a secondary small-aperture IOL in the ciliary sulcus six months after the initial injury. The effect was clear. Corneal topography did not change significantly (see Figure 3) and, three days postoperatively, the patient had an UCDVA of 0.8 and no longer experienced glare or light blindness.Burkhard Dick is professor of ophthalmology and chairman of the University Eye Hospital Bochum in Bochum, Germany.

References

- HB Dick, T Schultz, “Postmarket trial, interesting cases and posterior segment surgeries in a small aperture implanted eye”. Presented at the XXXIII Congress of the European Society of Cataract and Refractive Surgeons; September 5, 2015; Barcelona, Spain.