After many years of collaborative preliminary research by its creators, the London Project to Cure Blindness (LPCB) was officially launched in 2007, with the aid of a large charitable donation. This collaborative R&D initiative seeks to manifest the promise of embryonic stem cell technology in the fight against vision loss, and to devise specific medical treatments, tools and techniques alongside its ongoing scientific investigation. In an interview with The Ophthalmologist, one of the project’s originators and ophthalmic surgeon Lyndon da Cruz explained the background, clinical trial success and future plans for the LPCB’s retinal pigment epithelial (RPE) patch to reverse blindness in patients with severe wet AMD.

Pete Coffey and I started the preliminary RPE project in the early 2000s, after melding his interest in retinal disease cellular therapies with my focus on surgical remedies for AMD. Our aim was to create retinal pigment epithelial cells that could be transplanted into patients with this condition. This was always the great hope of stem cell treatment and regenerative medicine in general: to create a part of someone and transplant it into them to repair damage from disease and restore function.

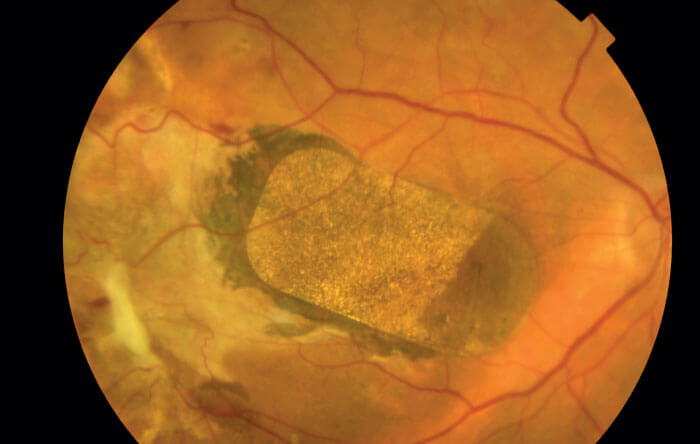

Over the past few years, we’ve been working together to both create the RPE cell layer or patch, and to develop the surgical trials, instruments and procedures necessary to actually put it into a human eye. We ran many preliminary surgical studies to determine the optimal installation time and tools for maximum therapeutic effect. We found that if we transplanted the RPE layer within the first six weeks after the sudden onset of vision loss, vision could be restored. All of this work led up to the two-patient trial that started in 2015, which enabled us to demonstrate clearly that our patients’ vision returned (1).

We were surprised and, of course, delighted to get such a clear signal of outcome from the first two patients. Usually when you're trying a totally new treatment, surgery and device, you just want to ensure it’s safe and practical. Later, you look for indications that the surgery works, the cells go where needed and survive, and they produce at least a two-year visual recovery. But for us, this outcome is fantastic.

We planned to study the procedure in more patients, but we were delayed when Pfizer, the study sponsor, stopped the trial for commercial reasons; transferring the project back to UCL took around three years. So, hopefully by the end of this year, we will start the trial again and would hope to have implanted the patch in another six to eight patients in the coming year, in order to determine if the initial effect we saw is repeatable.

We’ve now submitted the two-year outcome data for the first two patients to publication, to show that the RPE patch is safe and stable, that the visual recovery persists, that the patients have no major systemic or ocular side effects and require only minimal local immunosuppression. The fact that patients don’t have to take immunosuppression drugs for a long time is another benefit of this approach.

We’d like to confirm the vision restoration in a few more cases, and see the five-year follow-up data to make sure there’s no tumor growth, major rejection or damage to the other eye. Then we’d like to do a pivotal study to show that in severe wet macular degeneration patients, this is a reproducible endpoint, and we finally have a way of restoring lost vision. After that, our second phase will be to look at treatments for early dry AMD patients.

A group in the USA is doing a sheet pigment epithelium transplantation trial, but they chose a patient group with severe dry degeneration, with no chance of good visual recovery. It was a pure safety study, but it seemed to indicate the persistence of cells and pigmentation, like ours did. In other trials, rather than arranging the cells in a sheet, researchers have injected them into the eye in suspension. Some of these trials showed that clumps of cells survived, but it was very difficult to document whether those were the same cells introduced or if they were even functional. Other researchers are looking at replacing pigment epithelial cells in different disease contexts, but they’ve been unable to show conclusive visual recovery so far.

References

- L da Cruz et al., “Phase 1 clinical study of an embryonic stem cell–derived retinal pigment epithelium patch in age-related macular degeneration”, Nat Biotechnol, 36, 328 (2018). PMID: 29553577.

- Nature Research Bioengineering, “A cell patch for the treatment of blindness” (2018). Available at: https://go.nature.com/2lJbZXc. Accessed September 2, 2019.