Materials science is revolutionizing the modern world – whether through the carbon fiber of an F1 car or the artificial spider silk that makes clothes strong yet soft. But the materials revolution doesn’t stop at manufacturing; biomaterials are changing how we approach medical disciplines, with hydrogels, bioinks, nanoparticles, and many more formulations bringing new options to the ophthalmological table. Now, a group of researchers from Sweden have used collagen from pigs to create a hydrogel-based corneal tissue implant that has restored sight in 14 people who were previously blind (1).

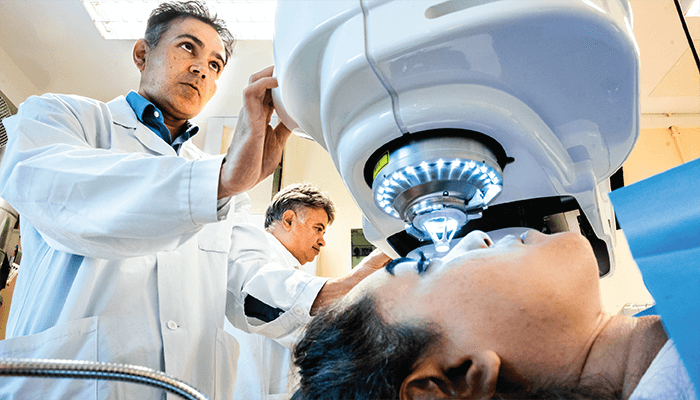

Not only can this biomaterial implant restore corneal-based vision loss, but the procedure is minimally invasive, with no sutures to be added or removed. Instead, a single incision allows the collagen disk to be implanted in the intrasomal pocket – without damage to the corneal cells or nerves – to counteract the thinning of the stroma and normalize refraction. The 14 advanced keratoconus patients who underwent the procedure had their vision restored to an average of 20/36 and were able to tolerate wearing contact lenses afterward. Analysis of the study results demonstrated a consistent increase in visual acuity and no operative complications or adverse events in the next year of clinical follow-ups.

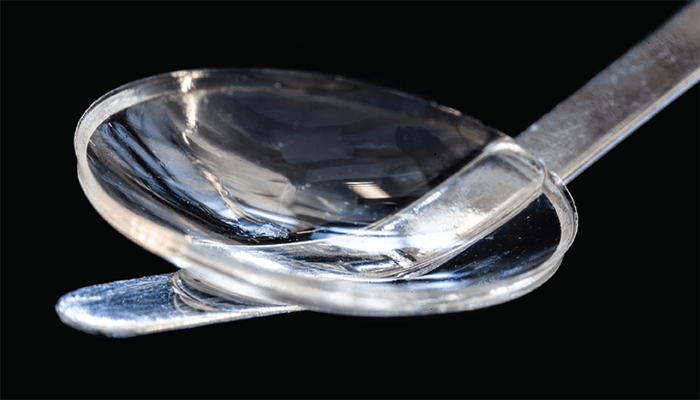

You may be wondering why the researchers didn’t use human collagen, given that the cornea is primarily made of human type 1 collagen. The group actually investigated using lab-grown human type 1 collagen, but found that the resulting quantity was low (and could not be scaled up) and the implant produced was too weak to be inserted into the cornea without invasive suturing. Pig type 1 collagen is produced in abundance as a byproduct in the food industry and is already used as a purified medical-grade material for a number of applications, including glaucoma surgery. To strengthen the pig collagen implant, the researchers applied chemical and photochemical methods to further cross-link the collagen to form a strong, transparent hydrogel for implantation.

The implants were shown to maintain stromal thickness after two years, but the authors predict from their unpublished data and knowledge of their materials’ mechanical strength that the stability should last for at least eight years. By not using sutures or damaging the cells and nerves of the cornea, the procedure also avoids the standard year-long postoperative application of corticosteroids. Instead, patients would need just eight weeks of immunosuppression and the damage caused is as limited as in minimally invasive cataract surgery.

Potential and limitations

Collagen-based hydrogels have the potential to revolutionize the corneal transplantation process. Potentially the biggest advantage to the procedure is that it sidesteps the need for human donor tissue, for which acquisition is a huge global challenge and a major cause of unnecessary blindness. In fact, the patients in the study would otherwise have gone without treatment due to a lack of donor corneas.The implant itself is not only sterile, but also has an ISO-compliant shelf-life, so it is both commercially and clinically viable. In addition, thanks to its use of a food industry byproduct, the implant is highly sustainable and removes the need for biobanking infrastructure.

Although the data shown in the research were impressive, the authors still identified severe limitations. The pilot study didn’t have patients receiving donor corneal tissue for comparison and patient selection and data collection were performed independently by local investigators. However, the patient outcomes recorded, the absence of adverse events, and the widespread lack of donor tissue availability make the new implant an attractive alternative to donor corneal transplantation. Robust future studies are now needed to truly ensure that this biomaterial lives up to the hype of its pilot study.

References

- M Rafat et al., Nat Biotechnol, [Online ahead of print] (2022). PMID: 35953672.