Corneal cross-linking (CXL) has evolved dramatically from its origins in the single, standardized “Dresden protocol” (1, 2). It is now a flexible, precision-guided treatment platform that can be tailored to almost the full spectrum of corneal ectatic disease (2). As understanding of corneal biomechanics, epithelial function, and refractive planning deepens, CXL is increasingly tailored to each patient’s phenotype, visual priorities, and surgical context.

So, how is personalization in CXL transforming everyday, real-world practice?

In this article, I will examine three practical clinical scenarios: patients with good vision, for whom effective modern epi-on strategies prioritize safety and epithelial preservation; cataract surgery in keratoconic eyes, where corneal optimization can improve biometric accuracy; and markedly irregular corneas, where customized CXL combined with excimer laser enhancement offers both biomechanical and optical benefits.

Together, these three scenarios illustrate how personalized CXL can enhance both corneal stability and visual quality in everyday practice.

Scenario 1: Patients with good vision – prioritizing safety and epithelial integrity

Epi-on CXL approaches as a risk-minimizing strategy

Historically, epithelium-on (epi-on) CXL has fared poorly compared to epithelium-off (epi-off) CXL. The epithelium acts as a barrier to riboflavin entry into the stroma – but this can be overcome with the use of either penetration enhancer compounds or iontophoresis. Oxygen is an essential component of the CXL reaction, and as the impact epithelium not only consumes oxygen but also acts as a physical barrier to its diffusion into the stroma, its continued presence limits the biomechanical effect compared with traditional epi-off approaches (3, 4). Additionally, earlier protocols were limited to a fixed fluence of up to 5.4 J/cm² – an amount that often fails to compensate for the reduced stromal availability of oxygen and riboflavin in epi-on procedures (5, 6).

However, epi-on CXL protocols have the advantage that the continued presence of the epithelium reduces the need to manage the pain and infection risk of a corneal epithelial defect until the epithelial cells have regrown, and modern epi-on protocols have been developed to mitigate the issues inherent with an intact epithelium in order to give an effective, lower-risk, higher-comfort alternative to epi-off CXL in patients with good vision or slow progression.

Recent advances – particularly protocols using optimized riboflavin formulations, controlled oxygen delivery, and fluence-adjusted UV-irradiation such as the ELZA-epi-on CXL protocol – have significantly narrowed this efficacy gap. When applied under controlled conditions, these next-generation epi-on strategies can approach the performance of accelerated epi-off CXL while preserving epithelial integrity (7-9). Early clinical results, including one-year data from our own group (7), are highly encouraging, with long-term follow-up expected to further define durability.

When maintaining the epithelium is advantageous

Epi-on CXL may be especially appropriate for:

• Patients with fragile or slow-healing epithelium

• Individuals at increased infection risk

• Those with ocular surface disease or limited postoperative compliance

• Patients with good vision and low rate of progression

Scenario 2: Corneal optimization in keratoconus with cataract

Patients who present with both cataract and corneal irregularity – whether from keratoconus, corneal ectasia, or prior biomechanical compromise – pose particular diagnostic and refractive challenges. Irregular astigmatism can render keratometric readings unreliable and reduce the predictive accuracy of even the most advanced intraocular lens (IOL) calculation formulas.

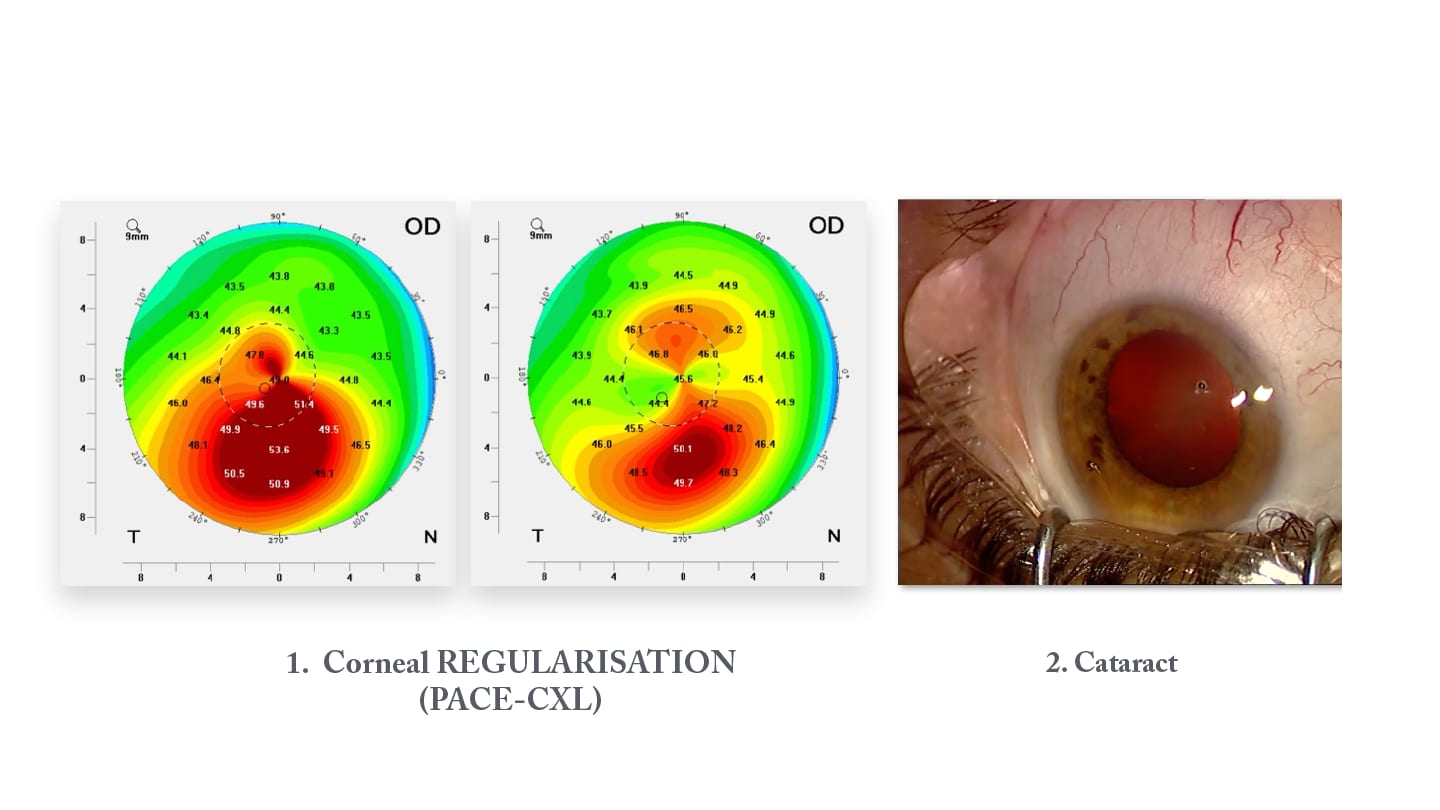

Optimizing the cornea before cataract surgery

When irregularity – especially within the central cornea and along the visual axis – is significant, pre-cataract corneal regularization is often a reliable route toward achieving more precise biometry and more predictable refractive outcomes. Restoring or improving corneal symmetry sharpens IOL power calculations and helps prevent postoperative surprises. Although formulas such as Barrett True-K-KC and Kane can assist, they remain limited by the upper bounds of keratometry and assumptions about corneal shape.

Potential interventions include:

• Intracorneal ring segments to bulk reshape the cornea. Typical options include:

o PMMA-made rings (10)

o Rings made from collagen or corneal tissue, such as corneal allogenic intrastromal ring segments (CAIRS) (11)

o Cross-linked CAIRS segments prepared extracorporeally using high-fluence CXL before implantation (ECO-CAIRS) (12)

• Phototherapeutic keratectomy (PTK)-Assisted Customised Epi-on corneal cross-linking (ELZA-PACE)-CXL to reinforce focal biomechanical weakness, with the intention of inducing differential flattening effects to induce extra flattening effects in the cone region (13)

• Total cornea (anterior + posterior surface) wavefront-guided excimer laser enhancement (in combination with CXL if not already performed) in carefully selected and stable corneas to reduce higher order aberration occurrence and improve visual quality (14, 15)

When cataract surgery takes precedence

When corneal irregularity has little impact on IOL calculations – or when staged procedures are impractical – performing cataract surgery first is reasonable, with corneal optimization reserved for later if needed. A careful review of the patient’s contact lens history is essential to avoid distorted measurements and ensure proper IOL choice.

Scenario 3: Markedly irregular corneas – combining customized CXL and laser enhancement

For eyes with marked asymmetry or irregularity, a staged or combined approach can offer the best of both stability and optical refinement.

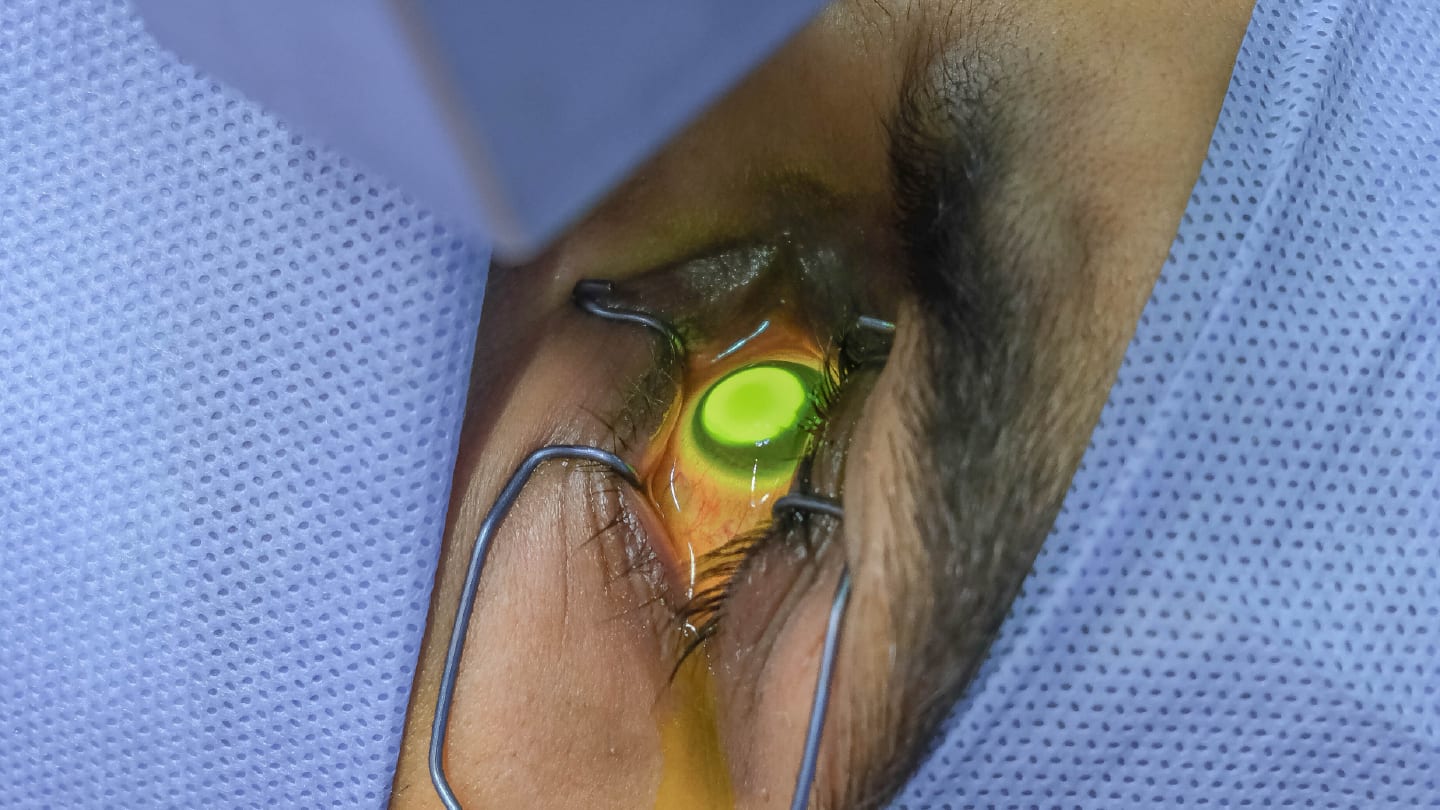

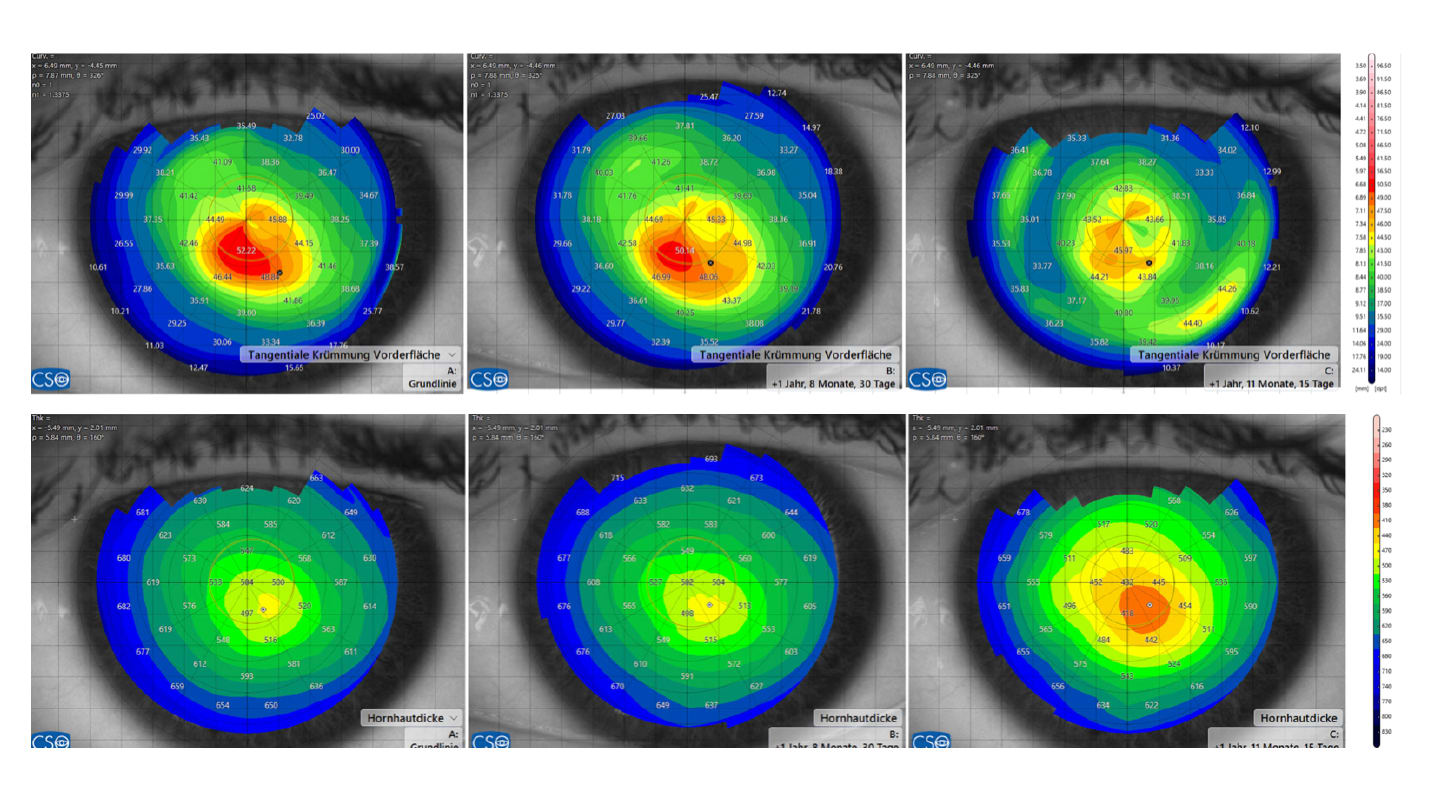

Customized ELZA-PACE-CXL

Phototherapeutic keratectomy (PTK)-Assisted Customised Epi-on corneal cross-linking (ELZA-PACE)-CXL selectively strengthens areas of biomechanical weakness, encouraging a more regular corneal shape without removing tissue (2). New topography-guided and gradient-controlled protocols enable localized stiffening while preserving epithelial integrity in other regions – a concept increasingly used as an intermediate step between stabilization and full optical rehabilitation.

Adjunctive excimer laser treatment

Once corneal stability is achieved, a topography-guided or wavefront-guided excimer laser treatment can fine-tune the corneal optics. Although reserved for carefully selected eyes with adequate thickness and biomechanical strength, this combined approach can deliver significant gains in visual quality when meticulously planned.

More recently, treatment platforms capable of incorporating both anterior and posterior corneal aberrations have been introduced. By accounting for the relative contributions of these two surfaces – particularly when a steeper anterior surface coincides with a more elevated posterior surface – their opposing optical effects can partially cancel each other out. As a result, the planned ablation may require substantially less tissue while achieving a more physiologically optimized corneal profile. In ectatic corneas, where tissue preservation is paramount, the ability to reduce the overall amount of tissue ablated becomes especially valuable. By enabling meaningful optical improvement while conserving more corneal tissue, these advanced algorithms represent a significant evolution in therapeutic excimer treatments performed in combination with corneal cross-linking.

From standardization to personalization: rethinking CXL

CXL should no longer be viewed as a one-size-fits-all procedure. It has become a flexible therapeutic platform in which technique selection can be tailored to:

• Progression rate and severity

• Epithelial behavior

• Patient age and visual expectations

• Refractive planning (including cataract surgery)

• Corneal regularity and optical requirements

Beyond stabilization

In selected cases, CXL can also contribute directly to optical rehabilitation – either through customized cross-linking approaches or, particularly, in combination with ICRS, cross-linked allogenic ring segments, or excimer laser enhancement. One of the major advantages – especially with customized CXL – is its tissue-sparing profile: because CXL removes no tissue and adds no permanent implant, it allows sequential or combined strategies that refine both biomechanics and visual quality.

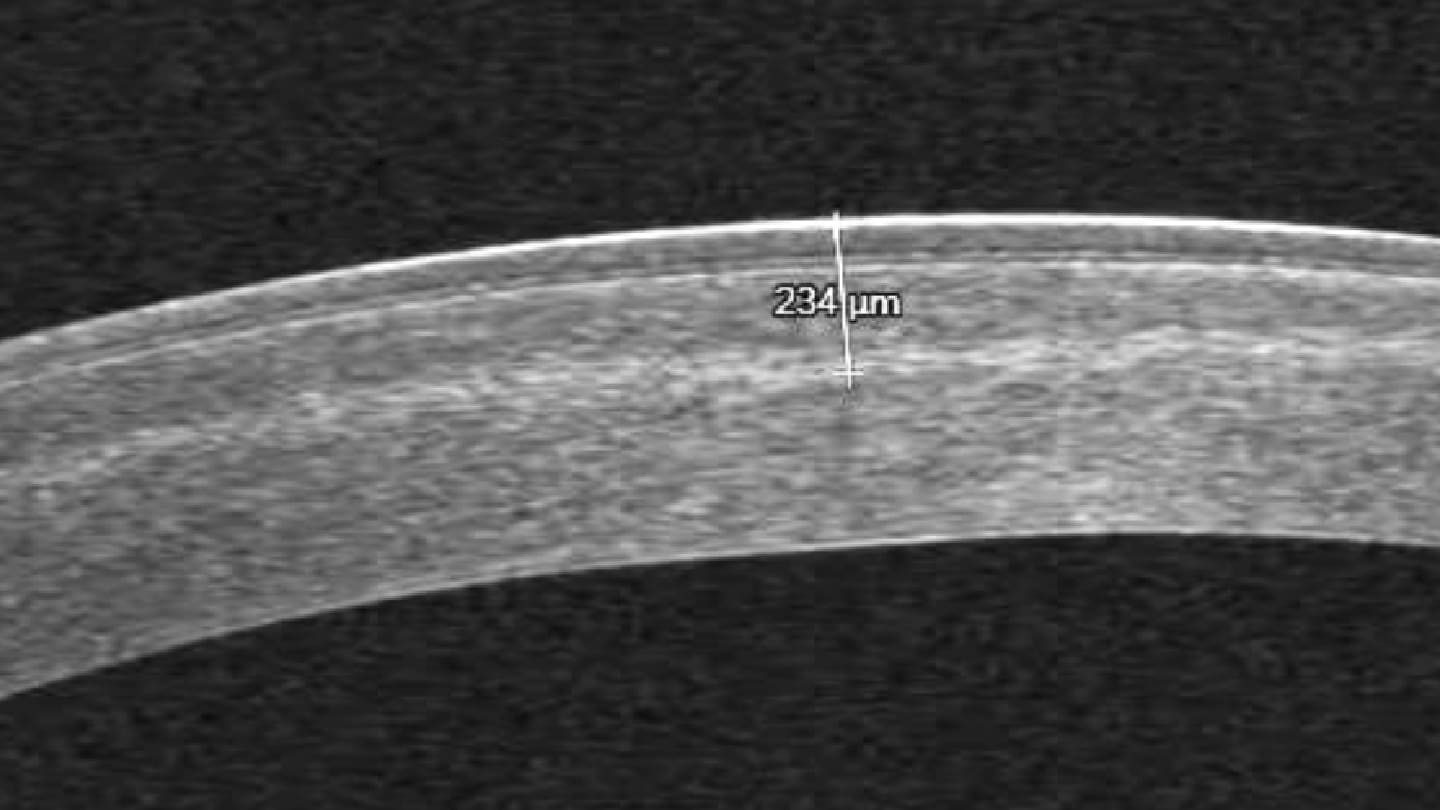

Corneal cross-linking has evolved from a single stabilization protocol into a truly personalized therapeutic platform – one that now spans nearly the entire spectrum of patients, from those with ultra-thin corneas, where stabilization can be safely achieved using the Sub400 protocol (16), to advanced cases in which meaningful visual rehabilitation is possible.

With the advent of phototherapeutic keratectomy (PTK)–assisted customized epi-on CXL, biologically cross-linked allogenic corneal implants, and high-precision excimer-laser fine-tuning used in combination with CXL, clinicians can now modulate corneal biomechanics and optical quality with a level of control previously unattainable.

By reframing CXL through real-world clinical scenarios, we align the technique with the broader movement toward personalized ophthalmic care – where stability, safety, and, when appropriate, visual excellence are pursued through individualization rather than standardization.

References

- F Hafezi et al., “Expanding indications for corneal cross-linking,” Curr Opin Ophthalmol, 34, 339 (2023). PMID: 37097193.

- F Hafezi et al., “Corneal cross-linking,” Prog Retin Eye Res, 104, 101322 (2025). PMID: 39681212.

- O Richoz et al., “The biomechanical effect of corneal collagen cross-linking (CXL) with riboflavin and UV-A is oxygen dependent,” Transl Vis Sci Technol, 2, 6 (2013). PMID: 24349884.

- F Hafezi, “Corneal cross-linking: epi-on,” Cornea, 41, 1203 (2022). PMID: 36107842.

- EA Torres-Netto et al., “Oxygen diffusion may limit the biomechanical effectiveness of iontophoresis-assisted transepithelial corneal cross-linking,” J Refract Surg, 34, 768 (2018). PMID: 30428097.

- C Mazzotta et al., “Enhanced-fluence pulsed-light iontophoresis corneal cross-linking: 1-year morphological and clinical results,” J Refract Surg, 34, 438 (2018). PMID: 30001446.

- F Hafezi et al., “Epithelium-on corneal cross-linking utilizing a modified penetration enhancer without supplemental oxygen or iontophoresis,” J Refract Surg, 41, e724 (2025).

- NJ Lu et al., “A transepithelial corneal cross-linking (CXL) protocol providing the same biomechanical strengthening as accelerated epithelium-off CXL,” J Refract Surg, 41, e724 (2025). PMID: 40626437.

- J Hill et al., “Optimization of oxygen dynamics, UV-A delivery, and drug formulation for accelerated epi-on corneal crosslinking,” Curr Eye Res, 45, 450 (2020). PMID: 31532699.

- JL Alió et al., “Intracorneal ring segments for keratoconus correction: long-term follow-up,” J Cataract Refract Surg, 32, 978 (2006). PMID: 16814056.

- S Jacob et al., “Corneal allogenic intrastromal ring segments (CAIRS) combined with corneal cross-linking for keratoconus,” J Refract Surg, 34, 296 (2018). PMID: 29738584.

- F Hafezi et al., “Extracorporeal optimization of corneal allogenic intrastromal ring segments (ECO-CAIRS) using ultra-high-fluence corneal cross-linking,” J Refract Surg, 41, e1233 (2025). PMID: 41212961.

- M Frigelli et al., “Predicting the effects of customized corneal cross-linking on corneal geometry,” Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci, 66, 51 (2025). PMID: 40985801.

- AJ Kanellopoulos, PS Binder, “Management of corneal ectasia after LASIK with combined, same-day, topography-guided partial transepithelial PRK and collagen cross-linking: the Athens protocol,” J Refract Surg, 27, 323 (2011). PMID: 21117539.

- MA Grentzelos et al., “Long-term comparison of combined t-PTK and CXL (Cretan Protocol) versus CXL with mechanical epithelial debridement for keratoconus,” J Refract Surg, 35, 650 (2019). PMID: 31610006.

- F Hafezi et al., “Individualized corneal cross-linking with riboflavin and UV-A in ultrathin corneas: the sub400 protocol,” Am J Ophthalmol, 224, 133 (2021). PMID: 33340508.