When evaluating patients with elevated intraocular pressure (IOP) or cataract formation, practitioners may focus primarily on primary open-angle glaucoma (POAG) or age-related lens changes. However, one condition, known as pseudoexfoliation syndrome (PXF), can masquerade as routine age-related ocular changes while silently progressing to cause devastating vision loss.

Although PXF is most commonly associated with elderly individuals of Northern European and Mediterranean descent, this condition affects diverse populations worldwide and can present earlier than many practitioners anticipate (1). The development of PXF is rooted in the systemic deposition of abnormal extracellular material, with ocular manifestations serving as the most clinically apparent signs of this complex disorder.

The pathophysiology of PXF involves the abnormal production and accumulation of pseudoexfoliative material: a fibrillar protein-glycoprotein complex that deposits throughout ocular and extraocular tissues. This material, primarily composed of fibrillin-1, elastin, and other extracellular matrix proteins, accumulates on the anterior lens capsule, ciliary body, iris, and trabecular meshwork (2). The deposition in the trabecular meshwork is particularly significant, as it impedes aqueous humor outflow, leading to elevated intraocular pressure and subsequent glaucomatous damage (3).

For practitioners, recognizing the subtle early signs of PXF is crucial for preventing irreversible vision loss. Studies indicate that PXF can be present in up to 25 percent of patients initially diagnosed with POAG, yet the condition often goes unrecognized in its early stages due to its initially asymptomatic presentation and subtle clinical signs (4).

PXF case study

A 72-year-old woman of Greek ancestry with a past medical history of hypertension, osteoporosis, and no prior diagnosed ocular disease presented to the ophthalmology clinic for routine eye examination after her optometrist noted elevated eye pressures during a screening visit.

The patient reported no visual complaints and denied any family history of glaucoma or blindness. She had not seen an eye care provider in over five years, attributing her gradually declining near vision to "normal aging."

On examination, her visual acuity was 6/9 in both eyes with mild nuclear sclerotic cataracts. Intraocular pressures measured 28 mmHg in the right eye and 26 mmHg in the left. Gonioscopy revealed open angles with moderate trabecular pigmentation bilaterally.

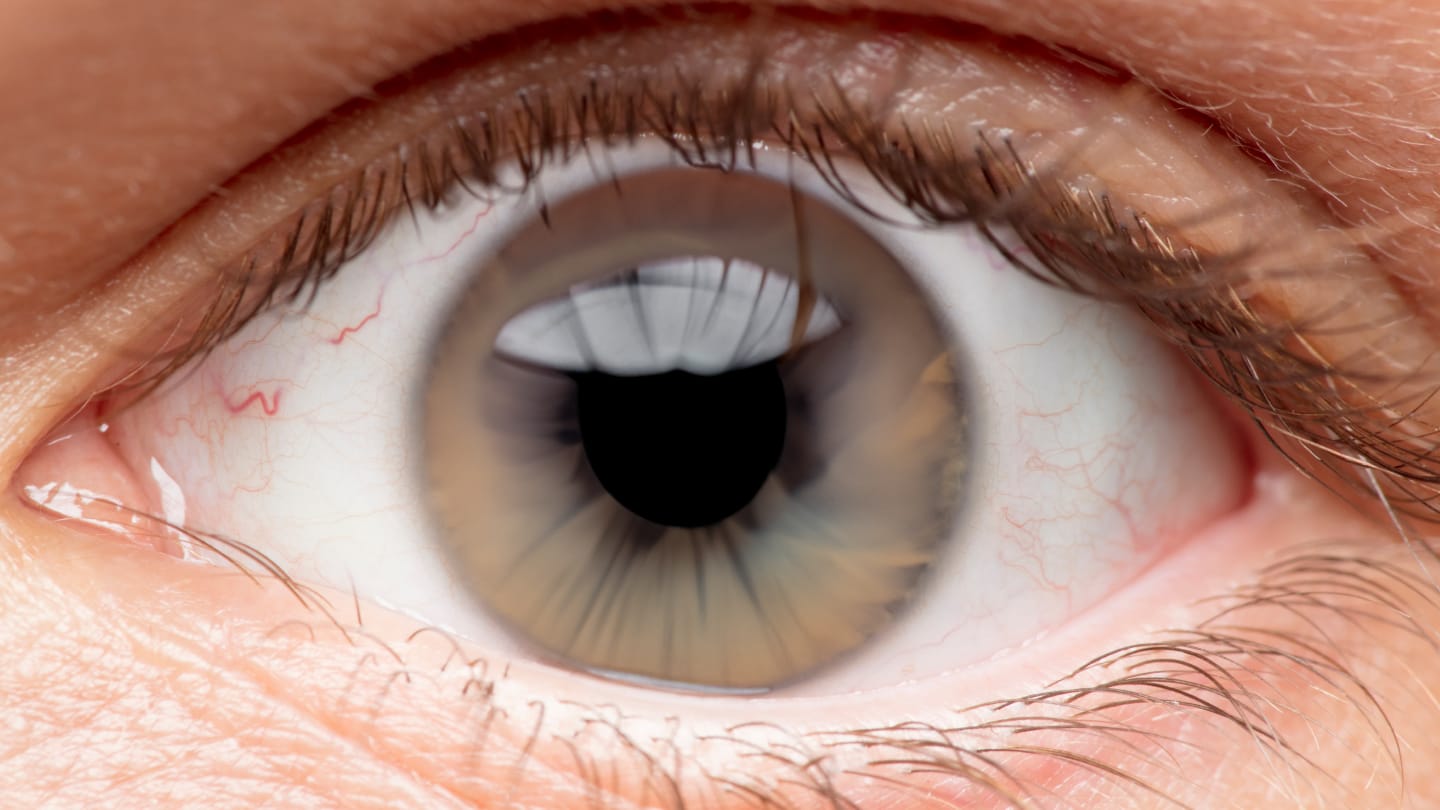

The key diagnostic finding was observed during slit-lamp examination. Under high magnification, a characteristic pattern of white, dandruff-like material was visible on the anterior lens capsule. This material formed a distinctive pattern: a central disc, a clear intermediate zone, and a peripheral band with a scalloped inner border – pathognomonic for pseudoexfoliative material deposition (5).

Further examination revealed additional signs consistent with PXF: loss of pupillary ruff pigment, transillumination defects of the iris, and increased trabecular meshwork pigmentation. Optical coherence tomography of the optic nerve showed early glaucomatous changes with cup-to-disc ratios of 0.7 bilaterally and mild retinal nerve fibre layer thinning.

Visual field testing demonstrated early superior arcuate defects consistent with glaucomatous damage. The patient was surprised to learn of these findings as she had experienced no symptoms.

Subsequent systemic evaluation revealed a history of cardiovascular disease and hearing loss – both conditions that have been associated with the systemic manifestations of PXF (6). The diagnosis of pseudoexfoliation glaucoma was established, and intraocular pressure reduction initiated.

PXF management

Given the advanced intraocular pressures and early glaucomatous damage, the patient required immediate and aggressive treatment. Initial therapy included a combination of topical prostaglandin analogue, beta-blocker, and carbonic anhydrase inhibitor to achieve target pressures below 15 mmHg.

The management of PXF requires a multifaceted approach addressing both the elevated intraocular pressure and the associated complications. Unlike primary open-angle glaucoma, PXF often requires more aggressive pressure reduction due to the typically higher baseline pressures and more rapid progression of optic nerve damage (7).

Surgical considerations in PXF patients are particularly important. Cataract surgery in these patients carries increased risks due to zonular weakness, which can lead to lens dislocation, vitreous loss, and postoperative complications (8). The presence of pseudoexfoliative material can also complicate intraocular lens placement and increase the risk of postoperative pressure spikes (9).

For the case study patient, staged cataract surgery was planned with careful preoperative preparation, including pupil dilation protocols and surgical planning for potential complications.

Patient education proved crucial in this case. The asymptomatic nature of early PXF means that patients often struggle to understand the urgency of treatment. The patient required extensive counselling about the progressive nature of her condition and the importance of adherence to her complex medical regimen.

Regular monitoring is essential in PXF management. These patients require more frequent follow-up than typical glaucoma patients due to the often unpredictable progression and the potential for sudden pressure spikes. The case study patient was scheduled for follow-up every 6-8 weeks initially, with plans to extend intervals once pressure control was achieved.

The systemic implications of PXF should not be overlooked. While primarily recognized for its ocular manifestations, PXF has been associated with increased risks of cardiovascular disease, stroke, and hearing loss (10). Coordination with primary care providers and appropriate specialist referrals may be warranted.

Ultimately, it is important that both patients and healthcare providers understand that PXF is a serious, progressive condition that requires lifelong management and monitoring. Early recognition and aggressive treatment can preserve vision and quality of life, but delayed diagnosis often results in irreversible visual impairment. The key to successful PXF management lies in maintaining a high index of suspicion in at-risk populations, performing careful slit-lamp examination in all patients with elevated intraocular pressure, and implementing aggressive treatment protocols when the diagnosis is established.

References

- R Ritch, U Schlötzer-Schrehardt, “Exfoliation syndrome,” Surv Ophthalmol., 45, 265 (2001). PMID: 11224719.

- M Zenkel et al., “Proinflammatory cytokines are involved in the initiation of the abnormal matrix process in pseudoexfoliation syndrome/glaucoma,” Am J Pathol., 176, 2868 (2010). PMID: 20395431.

- J Gottanka et al., “Correlation of pseudoexfoliative material and optic nerve damage in pseudoexfoliation syndrome,” Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci., 38, 2435 (1997). PMID: 9375560.

- P Mitchell et al., “The relationship between glaucoma and pseudoexfoliation: the Blue Mountains Eye Study,” Arch Ophthalmol., 117, 1319 (1999). PMID: 10532440.

- AM Prince, R Ritch, “Clinical signs of the pseudoexfoliation syndrome,” Ophthalmology, 93, 803 (1986).

- GK Andrikopoulos et al., “Pseudoexfoliation syndrome prevalence in Greek patients with cataract and its association to glaucoma and coronary artery disease,” Eye (Lond), 23, 442 (2009). PMID: 17932505.

- AG Konstas et al., “Diurnal intraocular pressure in untreated exfoliation and primary open-angle glaucoma,” Arch Ophthalmol., 115, 182 (1997). PMID: 9046252.

- BJ Shingleton et al., “Outcome of phacoemulsification and intraocular lens implantation in eyes with pseudoexfoliation syndrome,” J Cataract Refract Surg., 25, 810 (1999). PMID: 27230126.

- P Vazquez-Ferreiro et al., “Intraoperative complications of phacoemulsification in pseudoexfoliation: Metaanalysis,” J Cataract Refract Surg., 42, 1666 (2016). PMID: 27956295.

- Z Visontai et al., “Increase of carotid artery stiffness and decrease of baroreflex sensitivity in exfoliation syndrome and glaucoma,” Br J Ophthalmol., 90, 563 (2006). PMID: 16488931.