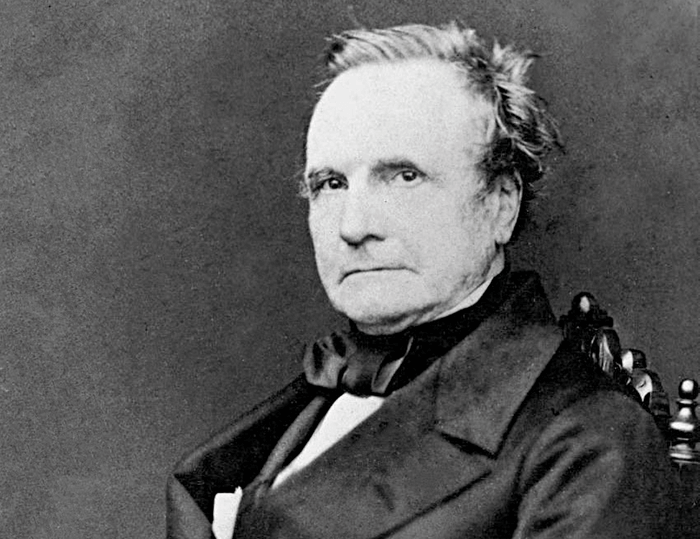

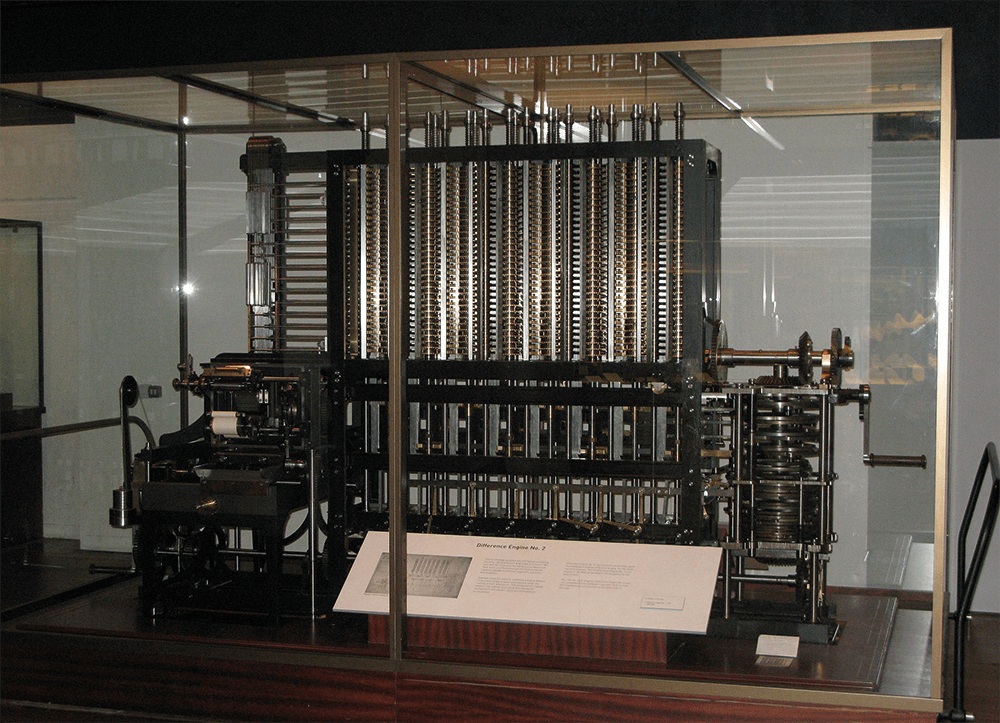

Charles Babbage was a famous English mathematician, inventor, and polymath, and he is regarded by some as the father of computing. Between 1828–1839, he occupied the Lucasian Chair of Mathematics at the University of Cambridge, UK – a prestigious post that has been held by the likes of Sir Isaac Newton and Stephen Hawking. Like his contemporaries, Babbage yearned to push the bounds of knowledge and innovation – and one of his dreams was to build a “difference engine” that could automatically compute values of polynomial functions; he hoped to introduce mechanical computations similar to early computers. Though work on a prototype began, it was never finished because of a lack of financing – when work stopped, the machine had 25,000 parts and weighed 13.6 tons.

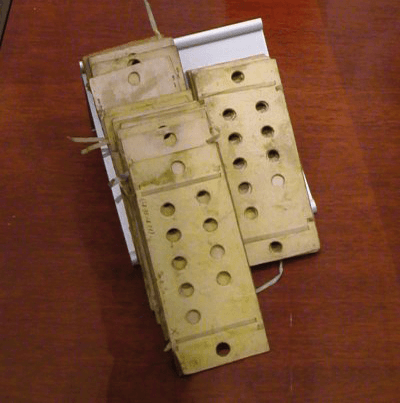

Towards the end of his life, Babbage designed a more complex “analytical engine” that represented a transition from mechanized arithmetic to fully-fledged general-purpose calculations. The proposed machine would be programmed with punched cards, have memory for 1,000 numbers of 40 decimal digits, and contain some elements that are still used in modern computers. In 2002, the first full-size “difference engine” was built; the culmination of a 17-year project, the machine was faithful to the original designs at the Science Museum in London and was capable of returning results to 31 digits.

Alongside these two engines, Babbage devised several other inventions, including the “black-box” recorder for monitoring the state of railway lines, theater lights that used colored filters, hinged flap shoes for walking on water, the metal frame attached to the front of locomotives that clears the tracks of obstacles (also called a cow-catcher), the dynamometer car, and – most important to our field – the ophthalmoscope.

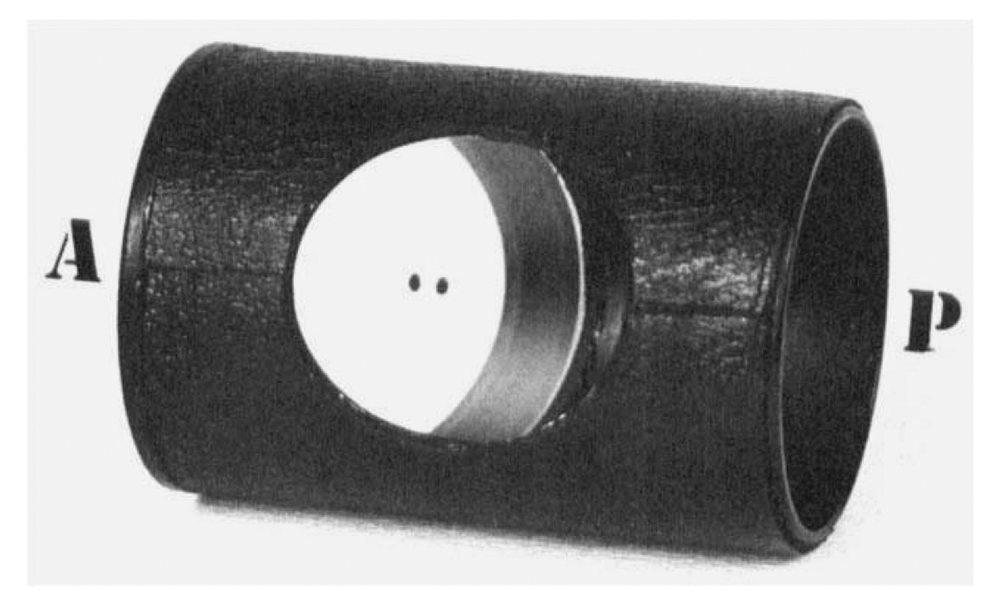

Babbage constructed the ophthalmoscope in 1847 and showed it to Thomas Wharton Jones – a prominent ophthalmologist and lecturer at Charing Cross Hospital in London, who would later become Professor of Ophthalmic Medicine and Surgery at University College London. Unfortunately, Wharton Jones was blind to the value of Babbage’s ophthalmoscope – likely due to his myopia, which might have left him unable to use it. According to Wharton Jones, who described the device in 1854, Babbage’s ‘scope “consisted of a piece of plain mirror, with the silvering scraped off at two or three small spots in the center, held within a tube at an angle so that rays of light falling on it through an opening in the side were reflected to the eye to be observed.” The investigator looked through the clear spots of the mirror from the other end. This concept was later successfully adapted and used in later models by Epkens, Donders, Coccius, Meyerstein, and others.

But what led Babbage to develop the ophthalmoscope in the first place? The consensus is that his problems with bilateral monocular diplopia, which he was able to partially correct with the use of a pinhole or concave lens, may have directed his attention to the fundus of the eye in an attempt to discover the origin of his own affliction.

Just three years later, in 1850, Hermann von Helmholtz constructed his own ophthalmoscope that revolutionized ophthalmology.

References

- C Snyder, “Charles Babbage and his rejected ophthalmoscope,” Arch Ophthalmol, 71, 591 (1964). PMID: 14109048.

- FW Law, “The origin of the ophthalmoscope,” Ophthalmology, 93, 140 (1986). PMID: 3513081.

- H Remky, “Ophthalmoskopieversuche vor Helmholtz,” Klin Monbl Augenheilkd, 193, 211 (1988). PMID: 3054262.

- CR Keeler, “150 years since Babbage's ophthalmoscope,” Arch Ophthalmol, 115, 1456 (1997). PMID: 9366679.

- CR Keeler, “Evolution of the British ophthalmoscope,” Doc Ophthalmol, 94, 139 (1997). PMID: 9657297.

- CR Keeler, “Babbage the unfortunate,” Br J Ophthalmol, 88, 730 (2004). PMID: 15148201.