Take us back to the beginning…

I have been with Orbis since 1994 – my first mission was to Khartoum, Sudan. I was just an ordinary ophthalmologist who had an interest in overseas ophthalmology, particularly in developing countries. One of the reasons I was interested in Orbis was because I learned to fly when I was very young and Orbis is where you get interdigitation of aircraft and ophthalmology! My first visit to Khartoum was a revelation to me; we regard ourselves as being well-trained ophthalmologists but when I got there I realized we hadn’t really scratched the surface. It was familiar… yet so very different. You’d see cataracts, but they weren’t the same as what I was used to; the response to surgery could be entirely different; for example, the patient could have a much greater inflammatory response. The burden of disease is absolutely huge – you just don’t realize how gargantuan the work is and how very little there is available with which to do it. There were patients who had walked for days to bring their child to see you in the hope that you could deliver a miracle for them. Sometimes you could, but sometimes you couldn’t.How does Orbis approach missions?

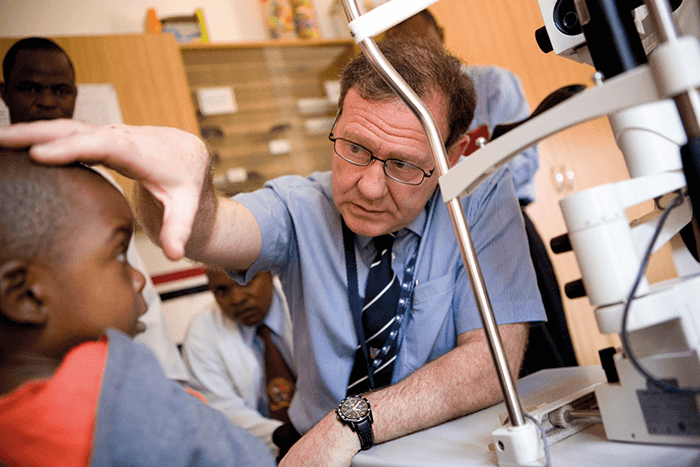

We are a capacity-building organization rather than a volume-based organization. We’re invited to countries by ophthalmologists who are working there and who’d like us to share our expertise. Then we select the volunteers. One very important point is that the work Orbis does is not about the ophthalmologists alone – it is about the whole team. On my own, I am completely useless. But surrounded by my colleagues – nurses, orthoptists, and the biomechanical engineers who mend and service the equipment – we can help and make a real difference.Tell us a bit about the new aircraft…

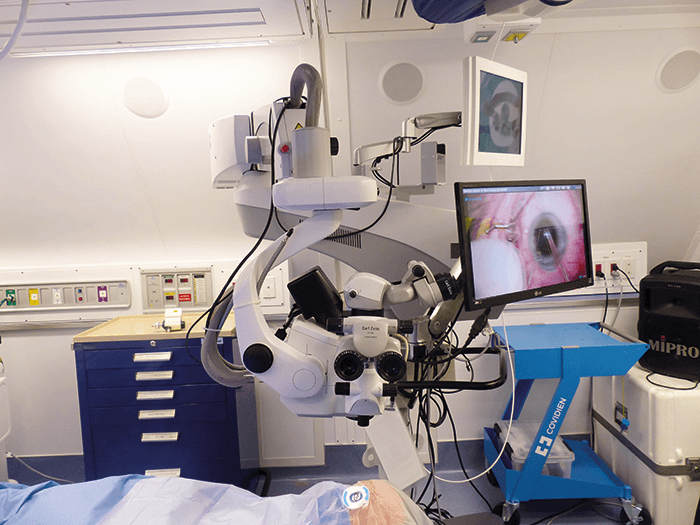

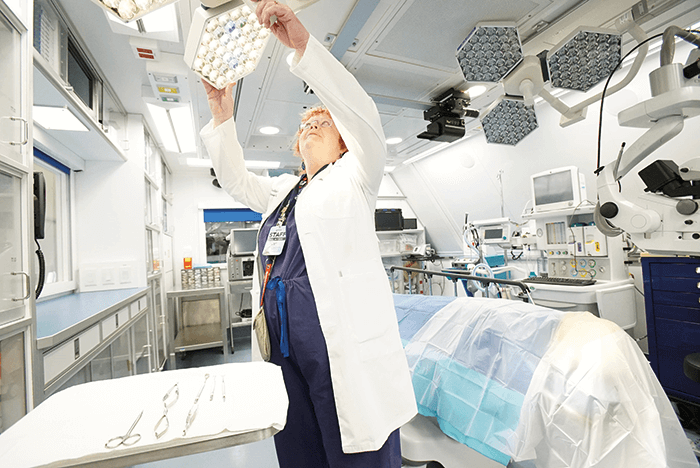

The Flying Eye Hospital is a very important icon for us. It is a state-of-the-art hospital that is internationally registered and recognized, and it can deliver top quality ophthalmic treatment anywhere in the world. It is a very significant investment, and has come almost entirely from donations; the aircraft itself was donated by FedEx. All of this has given us the opportunity to bring on board cutting-edge ophthalmic equipment. We have surgical simulators which are very important as they allow visiting ophthalmologists in the early stages of training to learn the basics of hand-eye coordination and ophthalmic surgery without needing to practice on people. There are many other technical aspects regarding the aircraft; payload, fuel consumption and where it can land – all of which are also much improved. Although its payload is still quite significant, it is a much lighter aircraft than our previous one, which means we can go to more places as we can land and take off on shorter runways. We try to keep it on the road – or rather in the air – as much as possible; there is no base, but there are periods of downtime when the airplane needs to be serviced for which we’ll go wherever we’re offered the best quality and best value maintenance. The Flying Eye Hospital is only a very small proportion of what we do. The majority of our work is providing country-based programs, and we currently have 15 offices across the world, and we will continue to do so until those countries no longer need us.What is your current role in Orbis?

Though I still operate in the UK, I no longer perform surgery on missions. I took a decision when I became Chairman of Orbis that I would cease volunteering medically. I am still volunteering, but I am doing different work now; I’m part of the committee that oversees programs to ensure we are achieving what we set out to, I’m involved in medical strategy and what our clinical foci should be, and I check that we’re spending our money appropriately. In 2017, Orbis will be providing eye care treatments for hundreds of thousands of people around the world and treating over six million people at risk of blinding trachoma, so it is a very big organization with a very small number of staff – around 220 worldwide.What are the main missions of Orbis?

If you look at where we spend most of our money, the three main areas would be in teaching cataract surgery, treating trachoma and pediatric ophthalmology. No-one can ignore cataract – it represents around 50 percent of the world’s blind people, and I think it is where we can reach out to the most people. Trachoma is a very important part of what we do, and one of our clinical interests is to eliminate it, which I think it is completely possible – just like smallpox was eradicated. We are incredibly grateful to Pfizer who donate azithromycin to us for the treatment of trachoma. They ship it to the country where we need it and through our in country partners, we distribute it for them. Our pediatric ophthalmology work covers a whole panoply of diseases, and with millions of blind and visually impaired children in the world, needless to say, there is a great deal to be done. We also perform many oculoplastic surgeries, as well as treat eye movement disorders.